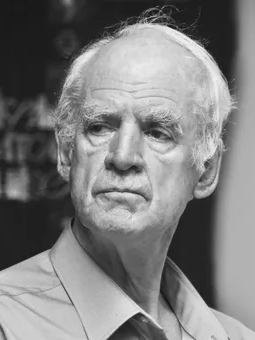

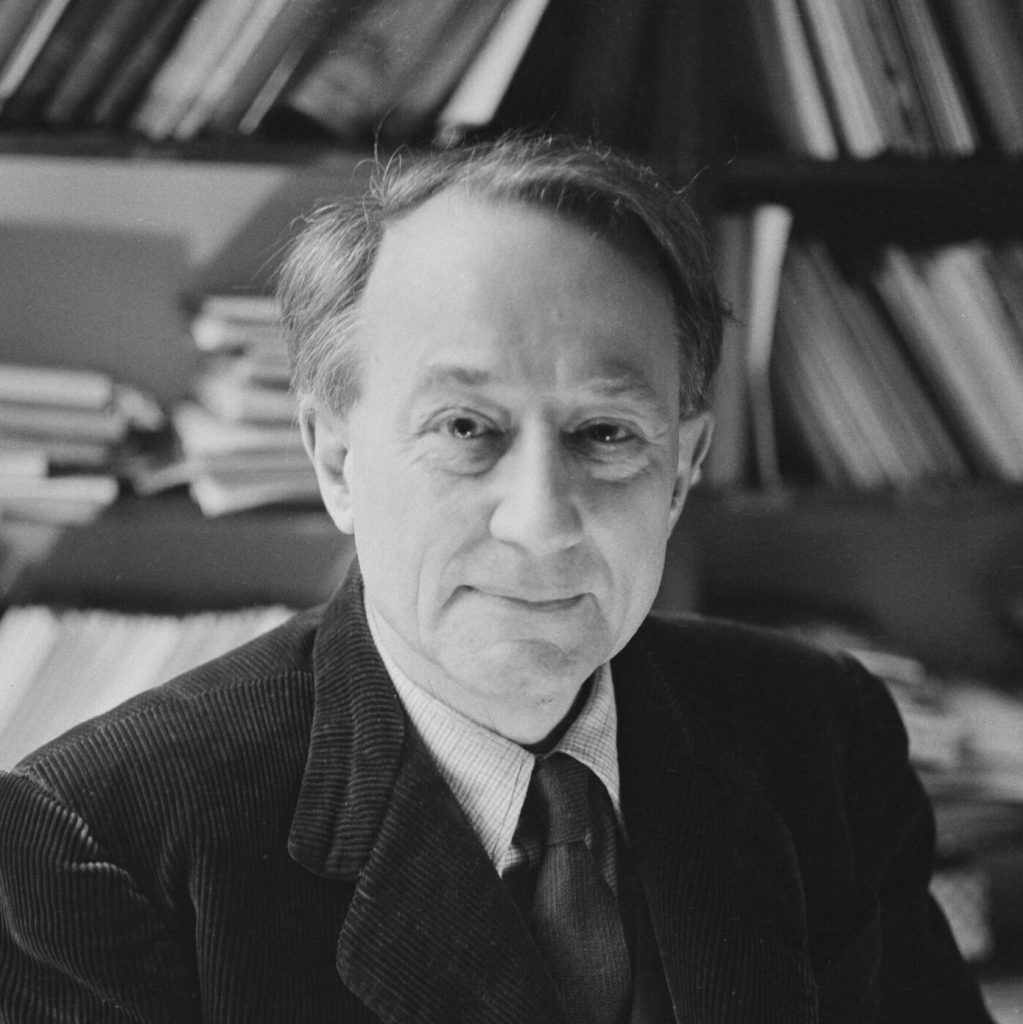

Two moral and political philosophers, Charles Taylor and Alasdair MacIntyre, have provided profound reflections on the nature of contemporary moral life, and—though their methods and projects differ—they come to intriguingly similar conclusions about the ills of modern ethics. The most notable, though described in different ways, is that of “individualism.” We might briefly understand this as the sense in which individual people are unmoored from the obligations that, historically, have come with social ties. The major effect of this transformation is increased moral strife and a general malaise in current life. In Taylor’s language, this is “atomism,” whereas MacIntyre leans into the notion of “emotivism.” I think each term has its benefits in what it highlights, though I will side with the former as I think it is more suggestive for my present purposes. Here, I outline a key element of atomization in order to better understand it: the problematic idea that narrative is fundamentally individual. Though this notion might be something of a half-truth, it neglects the broader ways in which the narrative unity of human life is made manifest. Both Taylor and MacIntyre sit behind what I say here, though I am sketching something with a different emphasis than either of them.

I should first clarify what I mean by ‘narrative unity.’ I follow both Taylor and MacIntyre (among many others) in thinking that human experience is fundamentally understood as narrative; to sound a bit more like Michael Oakeshott: we are what we understand ourselves to be. This is not mere postmodern or existentialist nonsense — this is a descriptive statement of the fact that we tell and are always telling ourselves a story about ourselves (who we were, are, and may be) that is made up of and informs our actions. Morality, then, is the art of making this series of circumstances as coherent, intelligible, and livable as possible. Importantly, even in Oakeshott’s formulation (despite his individualist tendencies), what is being understood is ourselves by us — we are the ones thinking and doing. I draw attention to this detail in contradistinction to it being an isolated I or you. The narrative unity that makes up a human life and helps us to consider the trajectory of our lives is fundamentally social. Though I hate this term, we might think of this as something of a ‘brute fact’ — an aspect of our thinking the denying of which makes us cease to think correctly. The very nature of human life as familial points to its inextricably social character; the great plight of many political theorists is that they neglect how the individual without a family simply does not exist.

Suggested here is, moreover, a complex of narratives. In suggesting that human life is social, I am not denying that there is a story specifically about me or you. My denial is that such a story could be told without many other stories; not only do I tell a story about me and you a story about you, but we are telling a story about us. There are, too, many different kinds of ‘us’ that we might think of. A marriage or family is an ‘us’; a group of friends is an ‘us’; a workplace is an ‘us’; a polity is an ‘us’; etc. What I wish to draw attention to is that both the ‘individual’ and ‘social’ narratives are mutually implicative: they cannot subsist without the other and profoundly inform each other. The greatest concession I may make is that there is a lesser agency to an ‘us’ than an ‘I,’ for ‘we’ hardly make unanimous decisions; but this does not undercut the structuring reality that an ‘us’ necessarily provides for all the involved individuals.

Given this background, I want to further flesh out the notion of atomization that Taylor talks about by reference to this narrative aspect of human life. When people colloquially refer to the atomization of modernity, they are often suggesting that people merely feel lonely or that there is a lacking sense of connection between people. I do not deny this. Rather, what I am suggesting is that such ideas are merely the effects of a deeper reality that can be highlighted by focusing upon the narrative element of all human affairs. Atomization, in my view, is best understood as an overemphasis upon the stories of individuals in such a manner that the social or collective narratives are diminished, damaged, or even destroyed. This is revealed both in what we do as well as how we talk about ourselves. This view can be detected in phrases that seem, otherwise, rather innocuous: “That’s just her truth”; “Do whatever makes you happy, and don’t worry about other people”; “He charts his own path, even if we can’t understand him!” In all these cases, what is neglected is how the individual self is often reliant on the very social reality that his or her decisions are negatively impacting. We can easily think of people who seem to forget their family and friends while pursuing their own interests — though this is hardly to say that they are not present to those social realities but merely that they are not considerate of them.

In highlighting the narrative component of human affairs, I am demonstrating how a profound loneliness can be present despite a person being continuously though merely outwardly social. If the problem of modern atomism is merely that people feel lonely or have a lesser connection with others, someone might reject the atomistic thesis by pointing out how much contact with others nearly everyone has today. People are constantly interacting, even if only by going to the grocery store, taking public transit, or walking past one another on the street. The isolationism that is often associated with atomism therefore seems overblown and sensationalistic. I think, however, that seeing atomism though the lens of narrativity makes it clearer how someone might be superficially social but deeply lonely. When we speak of the ‘story’ that makes us who we are, being the patron at the grocery store, the bus rider, or the stranger on the road hardly incorporates us into a broader story. Moreover, as workplaces become more standardized and employees become more replaceable, there is no sense that any particular person is necessary — a great insight of Marx’s notion of alienation. Loneliness is not about being alone; it is about telling one’s own story and realizing that it is entirely inessential to most or even all ‘social’ stories. Narrative isolation explains loneliness far more effectively than mere solitude.

When our narratives are cut off from broader collective narratives, they cease to have a sense of foundation or importance. I find it difficult to conceptualize how someone can answer the question, “Why are you doing that?” without eventually referring to the impact it has on others and how it is integrated with a greater social life that makes the specific life worthwhile. Modernity has seen a shift into what I think of as the burden of total self-making. Our individual stories must contain a richness and depth that they simply seem to justify themselves, perhaps the way that a Shakespearean drama — in all its vigour — simply asserts its own being in proper poetic fashion. But, even in the case of such artistry, we ultimately recognize the impotence of such poetic creations outside of a social context that celebrates them and the fact that even the artistic production itself suggests internally that there is no such thing as an individual narrative that is self-sustaining. This is the burden that contemporary moral life seems to bear, to which both Taylor and MacIntyre attend.

The attention that Taylor and MacIntyre give to history is, therefore, hardly surprising. They see in history the developing conditions that led to the present and in which a person now may find a particular set of realities with which they resonate. History, on their view, is the endeavour of perceiving a narrative that one now rests within and continues to tell. Neither Taylor nor MacIntyre seem to have any hope in the idea of total self-making; history, then, becomes the forum for reconstituting moral life by rejecting the atomistic suggestion that one can simply dream up a rich enough story for oneself. Instead, we are to ground ourselves in the ‘historically given’ and work from within those presuppositions toward a story that is better both for us and those of that same history. In some sense, both Taylor and MacIntyre exemplify the idea developed by R. G. Collingwood on what it means to develop a sense of duty through historical consciousness — a concept of which I have prior discussed and with which I am continually wrestling.

Here, however, I will need to admit of my skepticism. I take this view of history to be better thought of as ‘tradition,’ which is a way of situating oneself in time but from a practical perspective. History, in my view, is historiography; it is a specialized activity that is actually rather strenuous and suggests little if anything of what should be done in the present. History is a rethinking of the past for its own sake; it says virtually nothing about the present. I therefore take on a difficult position: I subscribe to the notion that human life is fundamentally structured by narrative and that we become the stories we tell about ourselves, but that this is an endeavour fundamentally distinct from that of the historian. What, then, is this sort of moral thinking that can resolve the errors of modern individualism? No doubt, it is a story, but it is the sort of story that one lives in. This can take on a number of forms that scale: perhaps a family believes it has a tradition of adventure in journeying to a new continent that informs one’s identity; perhaps there are tales of one’s town, province, or country that suggest what it means to be a member of those groups; and, perhaps most fundamentally, we likely need something akin to a religion to tell us what it means to be human, going beyond the particular. These stories may be informed by history and poetry but are never identical to either; they appear more like myths, not in the pejorative sense, but in that they provide a motivating, narrative structure in which we find ourselves.