An interlocutor in a debate I recently heard tried to suggest that there is an ultimately ‘subjective’ reality in every person that no one else can have access to or contest. In the context of the debate, he was arguing that there are things a person can recognize to be true about himself, and others have to act in accordance with such statements even if they disagree. What allegedly validates this move is that there is this profoundly ‘subjective’ part of each person that can be, somehow, asserted as ‘real’ or ‘true.’ He chose an intriguing example to make this claim: the phenomenology of colour. The brief version of this is that we have no way of verifying if the colours we see are the ‘same’ from a qualitative, internal perspective. Perhaps what I see as green you see as red and vice versa, but we have always heard such colours referred to by the same terms; ergo, we cannot determine the difference in our experience. In this sense, our individual perceptions might be incredibly different, and this can be rather startling to contemplate: what if the strawberry someone else sees is the inverse colours of what I see? This can strike us as a bizarre thought experiment, and such propositions can even seem to make some people lose their sense of ‘reality.’ (For a more extensive explanation, this video that unpacks the problem with much more detail and several intriguing tangents.)

I think, however, that this relies on a weak assumption that should be questioned, and doing so also reveals a critical aspect of language: it is impossible for language to reveal something that is purely ‘subjective.’ What I mean by this is not that language is incapable of being used to reveal something about one’s subject, oneself. Obvious examples are the ways in which we might use speech to reveal our emotions that are less apparent, our unknown intentions in a given circumstance, or some poetic fancy we dream up. There is something ‘subjective’ being revealed in all these instances, but to utter them to someone else and have them understood is to acknowledge that the very concepts we are using have a more-than-subjective quality. We are saying, ‘These are my thoughts,’ not, ‘These are my thoughts.’

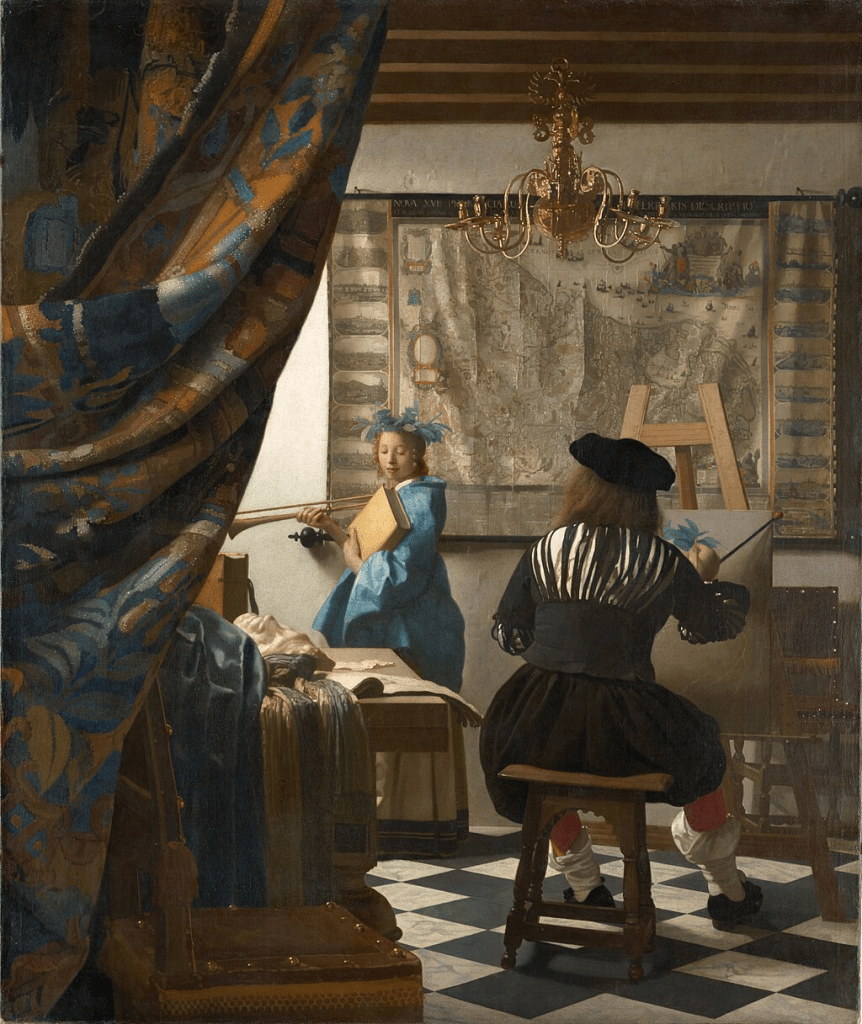

If I told my wife: “I am feeling quite keblipt today,” she would rightly look at me as if I were an alien. The reason is that this made up word, “keblipt,” is without any meaning; even if I somehow ‘knew’ what I meant by it, my wife would rely on me to use a variety of other words we share in common to make sense of it. We can compare this with the use of a word from another language that does not neatly fit into our own. A favourite of my wife (that she is regularly inspired by) is the Danish term “hygge” (pronounced ‘hoo-ge’) that means something roughly like an intense mood of comfort and coziness that is informed both by the atmosphere of one’s environment, like one’s home, and the company with whom that environment is shared. My wife and I can use hygge as an intelligible term in itself, but we frequently need to explain it to others who are unfamiliar with it. What this points out is that language is fundamentally intersubjective (which I think is a far better word than ‘objective,’ but that is another argument…). By this, I am claiming that language is grounded in shared meanings between people and is not reducible to any one person’s inner states, unless those inner states themselves can be accessed via the shared-meaning-framework that is a language.

Now, I should clarify that none of this suggests that someone cannot, like Shakespeare, simply invent new words that may catch on: from what I know, the term ‘savage’ used as a noun in King Lear was original to the English Playwright. But so too did Shakespeare use words that no longer have a recognized meaning in common parlance: the word “hilding,” used in various plays such as Romeo & Juliet, is an insult referring to a ‘base’ person (and often, problematically, when addressing a woman). Most people today are unlikely to recognize this word because it is not in our vernacular. We might then think of languages as allowing us a shared discursive basis for mutually thinking about reality, and words have referential truth acknowledged through common usage and sustained by their interrelations in daily conversation. There are, therefore, other aspects to be considered in the capacity for a language to be informative about the world: it must also correspond to our experiences and have a coherence within itself, but these too must be things that are intersubjectively adjudicated.

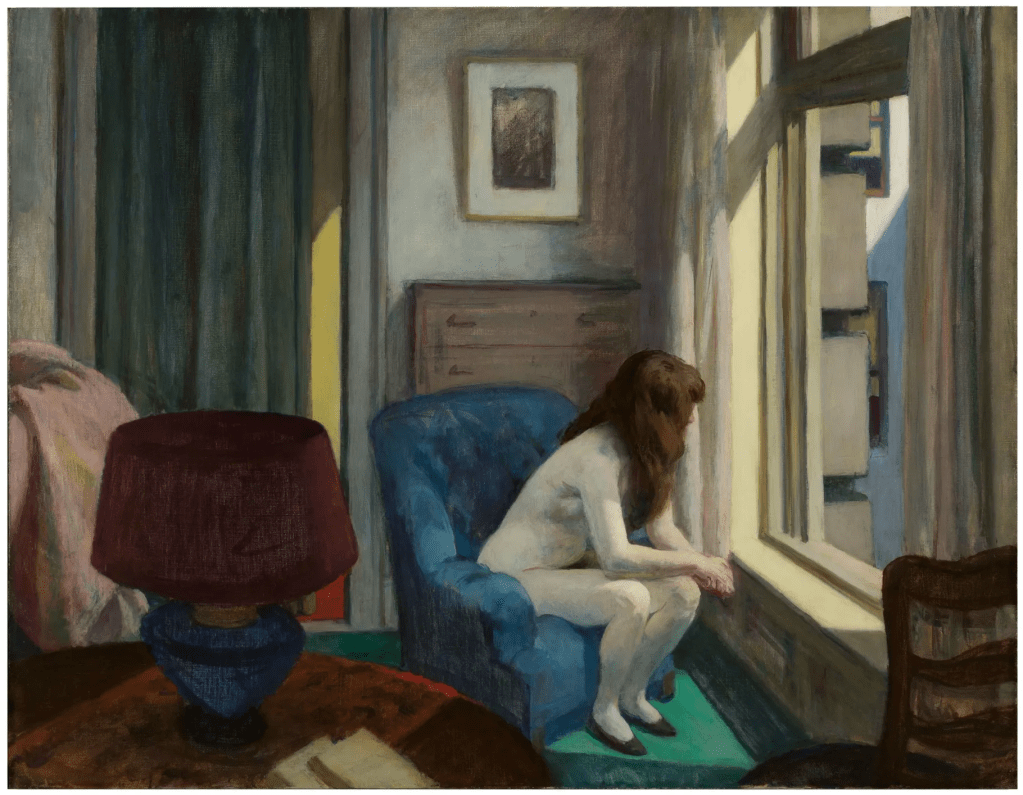

Let us, then, return to this supposed problem of the ‘subjective’ qualia of colour. I grant that, in theory, this is entirely possible; the description from physics that colours are dependent on the length of electromagnetic waves hitting our retinas and being processed by the brain could dismiss this possibility, but this does not entirely circumvent the philosophical problem of the experience of qualia (see the ‘Mary’s Room’ thought experiment for more on this). But this is a different question than that of language and how we think and converse together about experience. Let us restate the supposed predicament: two people may be perceiving colours inverted from the perception of the other but they use the same terms to refer to ‘opposing’ colours due to the manner in which they made associations within a shared language. The problem with this is that it is impossible to know: not only is it impossible for me to know this about someone else, it is actually impossible for me to know this about myself. What I mean by this is that the very framework in which I am trying to understand myself is mediated by this language which – as described above – is a shared, intersubjective reality. There is no way for me to know that there is this supremely subjective component of myself unless I somehow leave it entirely unthought by language – but this seems to me a problematic suggestion. Of course, if I try to convey it in language, I am ceding the ground to say that it is ‘merely subjective.’

If language is as I have described it here then the notion that someone could tell us that there is something about himself about which we cannot deliberate and disagree is nonsensical. To say that there are ‘subjective’ realities about oneself can, therefore, mean one of two things: there are entirely unthought, unmediated aspects of the self which are, consequently, unknown to both the subject and the outsider; or there are aspects that are relative to the self, and in this sense subjective, but which are nonetheless scrutable by anyone who can share in a conversation about that aspect of the self in question. This can be understood as a longwinded way of pointing out that there is no such thing as ‘subjective truth,’ at least in the sense that something is ‘true’ because the subject says so. To say that someone else cannot deliberate about my situation is only to suggest that the other person cannot fully understand the details of my circumstance and I have not the time to propositionalize it all for them. This may be practically true, but people frequently and mistakenly offer this claim at a categorical level; and, moreover, to acknowledge that this is practically the case is often lamentable, and I find it peculiar to think it a virtue or joy that someone else cannot understand me.

There is one small aspect of this debate that I have not acknowledged and which I cannot fully deal with here; but I also feel I cannot end without acknowledging this point: in eschewing the language of ‘objectivity’ and instead preferring the term intersubjectivity, I open myself up to the claim that there is no one intersubjectivity. More accurately, we must acknowledge that there are many intersubjectivities that are bound to times and contexts, and there are always a variety of them overlayed upon one another. An obvious example is how a person living in a secular culture may also have an alternative vocabulary and way of speaking if he participates in a religious community. The word ‘sin’ for the Christian can have a salience that it does not for the atheist or relativist (though this is not necessarily so). My quick response to this twofold: i) any given language is likely to have only a partial grasp of reality based on what it is used for, as is evidenced by terminology existing in one language or dialect and not another based on context; and ii) one cannot adjudicate which is correct without there being some sort of translation or common language recognized by the relevant linguistic communities. To say that two communities can have terms that mean contrary ideas is not to say that they are somehow both right; rather, we would need to adjudicate from within the different languages, dialects, or even idioms to ascertain their meanings from within and try to compare as adequately as we can, most likely coming to some sort of synthetic understanding (which is to say informed by both views though not necessarily equally so).

In brief, my claim is that language, by its very ontology, is intrinsically intersubjective. We cannot, therefore, suggest that the ‘subjectivity’ of a claim be used to prove it’s verity or that it must consequently be respected by others. A language is a shared inheritance, something that can change with use over time but which never foundationally transforms in an instant or at the whim of any individual. Even the linguistic innovator is dependent on the greater shared language staying the same, otherwise he cannot articulate his novel employment of whatever terms he is seeking to repurpose or invent. No doubt, there can still be misunderstanding, and the potential for us to be inadequate in our articulation of a given reality is always a risk. But this is a risk precisely because our failure should be seen as loss and pain – whereas the defender of the subjective, in this crude sense, must revel in not being known, either by himself or by the other.