In 1971, Judith Jarvis Thomson published an essay entitled, “A Defense of Abortion.” Therein, she attempts an argument that assumes human life begins at conception (despite her personal rejection of this claim) so as to take on the most ‘extreme’ position that is used by many ‘pro-life’ advocates. This ‘extreme’ view argues that murdering a person is wrong, and this makes abortion tantamount to murder because it is killing a unique human being who has been so since he or she was conceived. Thomson believes there must be a way around this charge. Otherwise considered, she is attempting to argue that – even if a person – a fetus does not have a right to be gestated and birthed (more pithily, a ‘right to life’). I am opposed in principle to Thomson’s argument, in that I believe abortion is a great evil, though I wish to not merely object to her conclusion here – I want to point out the frailty of her analogical reasoning (despite my appreciation of good analogies) and how this weakens her argument to the point of collapse.

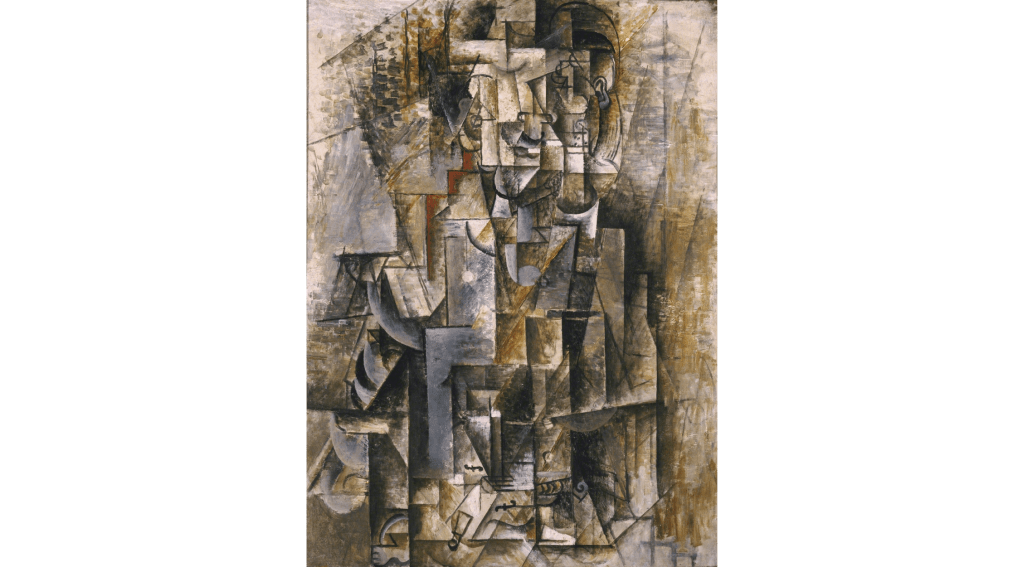

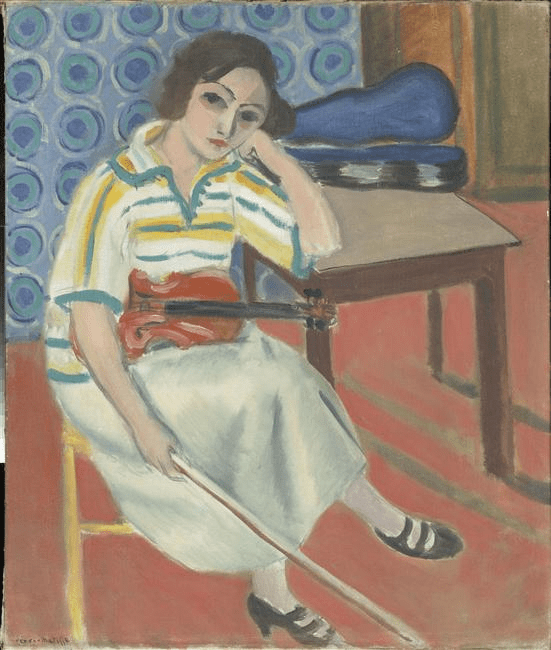

Thomson makes her argument in favour of permissible abortion by means of a thought-experiment: You awake tomorrow with a series of tubes in your back that have their other ends in a stranger beside you, and a nearby doctor tells you that this other person is a world-famous violinist (i.e., someone with great moral worth). While you were asleep, the doctor synced your kidneys together so that yours would help his function, because – if they did not – the violinist would die due to a strange illness. This had to be done with you because no one else’s body was capable of providing this procedure and remedy – you alone had this by chance. The doctor reassures you that this is not permanent but will only take about nine months for recovery. The analogical argument here should be clear. Much like a fetus, this concocted violinist from Thomson suggests that there is a person with moral worth who is depending on you for life despite that you did not agree to do so. This is not a permanent state of affairs but only about the length of a normal pregnancy. In Thomson’s view, it is outrageous to think that the victim of this strange operation should be required to remain hooked up to the violinist – and thus, on her view, we have a justification for abortion.

Despite the imaginative effort made, there are a number of issues with Thomson’s argument. The first is one made famous by Stephanie Gray: a uterus is for having children, whereas a kidney is only meant to sustain the life of the person in whom it rests; this is why organ donation is, though charitable, not a mandate. An organ specifically for the development of a child is simply disanalogous here. Second is the relation of the doctor to the victim in Thomson’s argument: one could argue that there must be a man who impregnates the woman and has a profoundly different relationship to her than the doctor does to the victim, which complicates the situation in a manner for which Thomson does not account. Third, the violinist has no genetic relationship to the victim or doctor; in the case of a pregnancy, these relations are obviously radically different as there are such intimate relations which, ostensibly, bring with them unique forms of obligation. Last, this situation (as had been widely recognized) seems to only account for situations of sexual assault, as the violinist was attached to the victim without any form of consent. The analogy, therefore, does not adhere to the circumstances surrounding most abortions – the vast majority of abortions are elective (meaning people pursued them because they voluntarily engaged in sexual activity but did not want the baby). Now, none of these criticisms amounts to the claim that abortion is immoral. All I am demonstrating here is that the pivotal breakdowns in the analogy are enough to make us doubt the validity of Thomson’s argument – we can leave it open that some other argument could arrive at the conclusion at which she aimed but, evidently, failed to arrive.

This is not, however, the only faulty analogy present in Thomson’s argument. Another criticism of her paper, related to the last one noted above, is that pregnancy almost always results from freely chosen sexual relations. This response points out that everyone knows sex risks pregnancy, and the fact that one does not want the pregnancy despite wanting to engage in sexual activity is irrelevant – it is no different than complaining about heart palpitations after consuming an unseemly amount of caffeine simply because one likes coffee or energy drinks. This rejoinder is especially effective because Thomson already granted the personhood of the child: we could return to that debate, but Thomson was precisely trying to avoid it. In trying to answer this objection, Thomson preemptively offers an image to act as a response: suggesting that engaging in sexual activity entails an openness to pregnancy is like saying that someone opening their window to allow a draft through their home on a warm night is inviting in a burglar.

No doubt, this analogy seriously fails. In so saying, Thomson is separating the action from its consequences as if the latter is a non-sequitur from the former; she writes of this as if it is as disconnected as a man being handed a goat because he chose to enter a restaurant. This is obvious folly, otherwise the revolution of chemical birth control in the 1960s would have been nothing of note. Moreover, she misses that the ‘intruder,’ so-to-speak, in the form of a burglar has agency whereas the fetus (ostensibly also considered by Thomson as an ‘intruder’) had no will in the process of its supposed ‘intrusion’ – which is why the doctor is necessary in the violinist image and the latter could not have simply hooked himself up to the victim. Though I typically aim for charity in interpreting others’ arguments, we must recognize how pathetic this analogical attempt is from Thomson; the incongruencies between her image and their practical correlates is so stark as to leave us scratching our heads wondering how she ever thought them persuasive.

My point in outlining all this is not only to demonstrate the failure of Thomson’s argument but also the difficulty of arguing by analogy. An argumentative analogy is meant to highlight an aspect of our thinking about a problem by reference to a different scenario that may not prime our learned, knee-jerk reactions. In other cases, it may act as more accessible image for conveying a complex idea that is difficult to discern in day-to-day particulars. There are plenty of examples that are moving and informative, such as Plato’s ‘Allegory of the Cave’ or Michael Oakeshott’s ‘Ship of the State.’ My suggestion is hardly that people should not use analogies but that they must be judicious in doing so; and those of us who read them (especially when we agree with their supposed conclusions) must be vigilant in ensuring that the crucial aspects of the analogy are congruent with the referential scenario they are meant to illuminate.

I can make this point in the other direction by reference to a joke from Bill Burr. In his comedy special Live at the Red Rocks, he discusses abortion explicitly. He believes that women should have the right to choose abortion, but he also says it is obviously killing a baby – a position he recognizes as peculiar. Nevertheless, he explains his latter belief by saying that rejecting that a fetus is a baby is like if someone took a cake pan filled with batter out of the oven just five minutes after the baker put it in and threw it across the room. The baker would understandably yell, “Hey! You ruined my cake!” If the cake-ruiner said, “Nice try! It wasn’t a cake yet,” the baker could easily retort, “It would have been, had you just let things be as they were!” Again the point of the analogy is fine, but this has many weaknesses too. A cake does not require nearly as long as a pregnancy, and it requires no physical toll akin to that of a baby in utero; the cake is for consumption and does not come with subsequent obligations; and no one is morally affronted (at least not in a deep way) by the loss of a cake. Again, this does not nullify the conclusion of Burr’s joke (nor its humour), but I would not seriously stake an argument on it. The sole reservation I have here is that I think Burr’s analogy is actually stronger than Thomson’s – though not by much.

This discussion of argumentative analogies may be read as a vindication of Thomas Hobbes when he suggested that those who “observe [comparative subjects’] differences and dissimilitudes, which is called distinguishing, and discerning, and judging between thing and thing…are said to have good judgement.” In this sense, we need not only critique Thomson’s position but thank her for allowing us to exercise our own judgement in contrasting her analogies with the real-life ideas that she is attempting to clarify. But, as I have invoked him, perhaps we should heed another suggestion of Hobbes from that same work: “And on the contrary, metaphors, and senseless and ambiguous words, are like ignes fatui [fatuous fires], and reasoning upon them is wandering amongst innumerable absurdities; and their end, contention and sedition, or contempt.” I myself do not wish to go so far as to lose the baby along with the bathwater, but perhaps we can appreciate that old Englishman’s skepticism in face of such arguments as Thomson’s – or we can at least remember the weaknesses of such failed analogies as we seek to write our own.

Glad to see this blogger back at it—mirabile visu!

LikeLike