For Geoff

In a culture so deeply saturated with governmental idioms and ideological jargon, we have lamentably allowed a term of great importance to fall into disrepair in our discourse and thought: conservative. This word surely has salient meanings that are well outside the realm of governance and party ideology, though—in my experience—people tend to treat the term as a bad word in nearly all realms. Why this is the case is likely to have a myriad of explanations, and my intention is not so much to weigh in on that complicated history—though I will note that the notion of conservation has a much longer history than any party brandishing itself with the label Conservative. Instead, my hope is to provide a simple explanation that might justify why we should attempt a reclamation of this term, finding in it much worth preserving that we have neglected to notice. Most fundamentally, I believe that a conservative disposition is essential to the maintenance of our identities—our sense(s) of self—that sits at the heart of a well-ordered and desirable life; to be conservative, on this view, is to desire to live in a world that is at least partly known, stable, and iterable. If novelty is to be embraced, we can only do so upon the foundation of these qualities that protect our individual and collective habits of living.

I might first clarify what I mean by a ‘disposition.’ By this, I simply intend an attitude that entails certain habits of thought and action, though I take this notion to be less substantial than that of character—though a conservative disposition may, no less, be a key aspect of a man’s character. A disposition may appear to us as an innate proclivity with which we are seemingly born or something that can be developed through deliberate attention and effort. A disposition can be fostered or avoided, and each of us will wrestle with different dispositions in a variety of ways. What should be noticed here, however, is that any given disposition entails no particular viewpoints or moral claims; depending on one’s philosophical anthropology, one may be more or less inclined to believe that a conservative disposition will entail a variety of disparate, concrete beliefs.

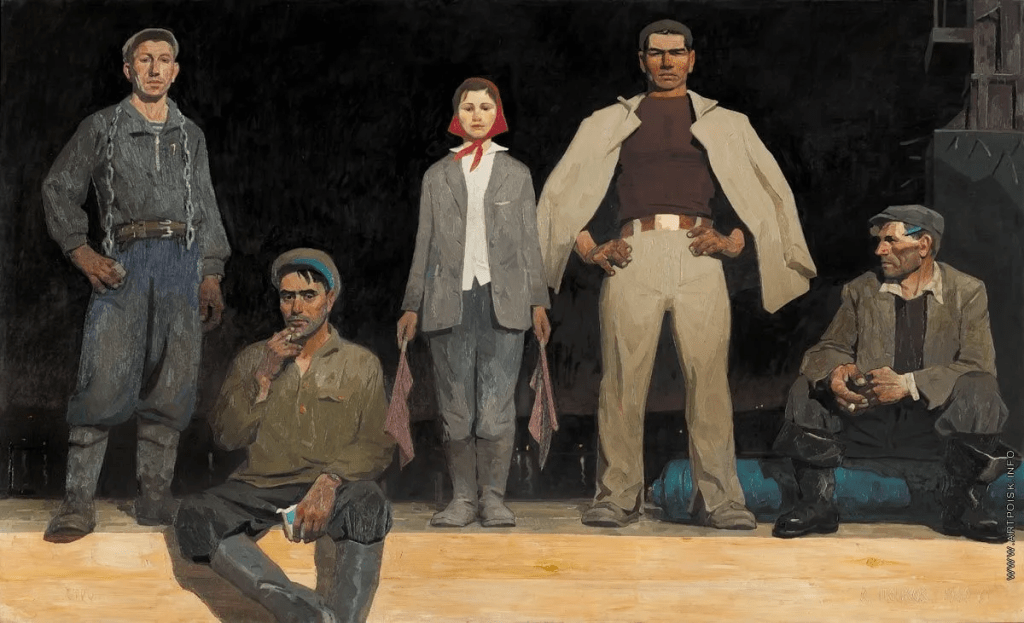

That last point should further distance what I am speaking about from anything like an ideological creed, especially of the party-based varieties. Many people today believe that to learn someone is conservative is to also suggest that we know many of the specific beliefs they will have and act out (though even these are subject to historical and geographical variation): they are more likely to be pro-life; they probably don’t like taxes very much; they likely have a rather exclusive view of marriage; they may appear more prudish or stern than other perspectives; they tend to be less creative and merely uphold the status quo. What I am describing as the conservative disposition, however, inherently entails none of these claims. To argue by an example: I have heard stories of Soviet men and women in their seventies experiencing the collapse of the U.S.S.R. in the late 1980s and lamenting its loss; the Soviet system was all they ever knew, and thus they wanted to return to it as opposed to adopting some new manner of living. This, in the sense I am describing, is no less an impulse of the conservative disposition than was that of the Royalists who sought to preserve l’Ancien Régime after the Terror in late eighteenth century France. What unites these Russian and French conservators is nothing even approximating a common metaphysical framework or ideological creed dictating the specific ways in which one must live—their similarity is found only in their proclivity to live in a world that has become suffused with their very being, a claim that I feel deeply moved by in both cases regardless of whether I may agree or disagree with their particular modes of living.

In choosing those examples, however, I may be misunderstood to still be playing into the idea that being conservative is merely a political phenomenon. Though I believe that this disposition can certainly affect politics, I am making the case that conservative sentiments have an even deeper grasp on us that we, nowadays, tend to recognize or believe. The easiest example of this is the loss of loved ones; when death takes those who are closest to us, the conservative disposition both pulls at our hearts but also provides us with the strength to move through the pain and keep up with all the other obligations that impinge upon us. (Though, lamentably, this conservative inclination is also perhaps why the death of a parent is so destabilizing for young children—so many of their daily habits are lost in such a tragedy, and they are trying to conserve what no longer exists but is nearly all they had ever known.) We desire to keep what we have, and grief after a death emerges as a brief grace in which we are allowed to desire something that cannot be: the return of our loved one. But so too does our desire to keep our many other relations in order cause us to acclimatize to our new and, evidently, impoverished reality. The conservative disposition thus informs the pain of loss but also its overcoming.

To be conservative, as I see it, is best understood as an existential claim (even if only taken provisionally—naturally, for a skeptic); we might think that the desire to conserve is tied into the fabric of our being at the most general level, or at least it seems that it is unavoidable in what anyone experiences. How we understand our existence, then, is essential for understanding the importance and place of the conservative disposition in human affairs. Despite the seemingly grandiose nature of what such a claim would need to entail, I can keep it rather simple for now: the world we live in is one of change. I do not necessarily mean that existence is in perpetual flux but rather that all things are always in motion for us. That movement may be lawlike in its regularity or have some indeterminacy, but the precise nature of change need not be entirely hashed out to make this point. At a more grounded level, we can make simple, everyday observations: the sun will rise and set, the grass will continue to grow, and the days will wear on my mortal frame. Having recognized the ubiquity of change, we can then make the second observation: we human beings are a peculiar kind of creature that self-consciously participates in this continual movement of creation. We track the sun to use it for our crops more effectively; we trim our lawns with some regularity; and we may attempt to remain in shape so as to stave off the inevitability of death.

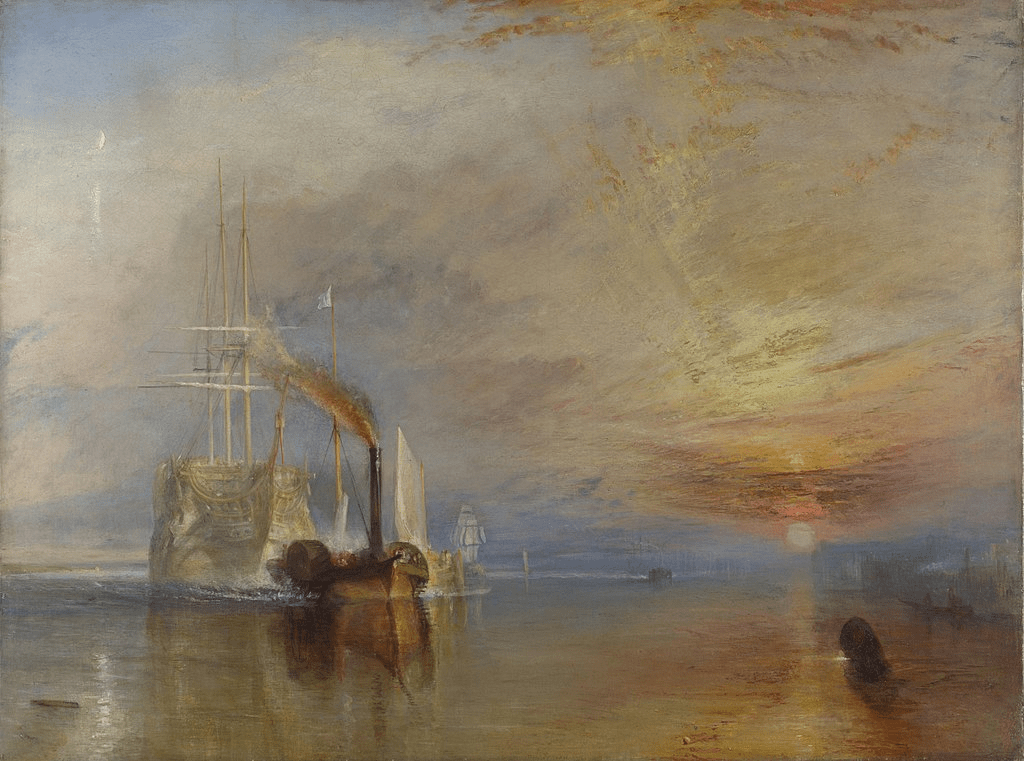

Our capacity to interact with the continual movement and change of the world can be conceived under two general responses: that of conservation and that of innovation. Where conservation—as already discussed above—is the attempt to maintain something in the face of inevitable change, innovation pushes in the opposite direction of actively furthering change, usually in the hope of making the world more amenable to our desires. Per this description, we can understand innovation to be the dispositional counterpart to conservation as I have been outlining it. In my view, conservation and innovation are inherent to the human condition and we cannot expel either from our lives. To say this is not, however, to suggest that these dispositions play equal parts in our experience. Indeed, part of my concern is that people today are focused almost exclusively on the promises of innovation and the hope of tomorrow—a disposition that leads one to always live for the morrow and never the day, but this is getting ahead of myself. For now, I can only point out that we are an age that is addicted to thinking of itself as always ‘making progress,’ though the irony is that this progress has led us to such evaluative vacuity that we no longer know toward what we are progressing.

Why do I make this claim about the emptiness of an age addicted to innovation? The answer is quite simple, but our epoch is curiously incapable of perceiving it: in order to know how to innovate, one must know what is wrong, and to know what is wrong requires that one have a sense of who (or what) he is and how he acts. To be devoid of identity makes innovation itself impossible; if I have no sense of a given activity or identity, I can never know how to improve it (or, insofar as I have but shallow understandings of these realities, I will have a proclivity to err). To use a facile example: I worked at McDonald’s from when I was fifteen to twenty, and I eventually worked as a manager; a funny thing that all managers spoke of was how new employees would approach us so seriously with suggestions for ‘improvements’ that were—at best—laughable. The new employees simply did not understand how little they knew the restaurant and company, so they would make suggestions that would affect dozens of things in a manner they were not intending but had insufficient awareness to perceive. No doubt, there are times when a given McDonald’s procedure is updated and there is legitimate innovation, but this is a radical minority compared with the hundreds or even thousands of regulative procedures that are repeated each and every day to ensure continuity.

Despite that McDonald’s may seem a silly source of reflection, I believe that this experience is no less true for our own identities as human beings embedded in our many contexts and perpetually performing our many habits. We are, in some fundamental way, the continuity (or not) of our actions; we make our choices and our choices make us. We identify with what we do, and thus our identities are entirely bound up with what we conserve about ourselves, knowingly or unknowingly. What this suggests, however, is that any innovation must fundamentally become a place of conservation, and every innovation we perform needs to be accommodated to the many aspects of our lives to which we are conservatively habituated. If this is not the case, we will have actually performed no innovation at all, but only some kind of aberration. Insofar as innovation seeks to improve our lives, it is reliant on our capacity to modify our current habits and make that novelty seem no longer novel as quickly as possible—in brief, innovation is existentially dependent upon conservation.

This is hardly an exhaustion of this topic, but I provide this only to provoke a greater sense of reflection on the ramifications of being so prejudiced against the claims of conservation. Ironically, we have come to conserve in our habits of mind and action an anti-conservatism without seemingly being aware of this fact, and this contradiction will—and perhaps already has—destabilized our capacity to be in the world with a sense of surety and care. Nothing about this suggests that a conservative disposition is sufficient for living a fulfilling human life, but I am willing to stand by the claim that a satisfactory life is impossible without acknowledging our need to conserve. Surely, there are other aspects of this notion to unpack: can one conserve in an innovative manner? What are the implications of this counterintuitive movement? If we do agree on a fundamental set of human conditions, what does the conservative disposition imply for them? Will not this understanding of conservation as I have articulated it undercut much of what is considered Conservative in common parlance? These, and many more, are all questions to be conserved for another day.