For A. J. S.

In his Confessions, St. Augustine of Hippo articulates his well-known though questionable understanding of babies: he attributes to them a sinfulness and malice that has caused many readers to accuse the African Bishop of lacking compassion and sensitivity for human infancy. A friend of mine has, however, tried to persuade me of an alternative reading of St. Augustine’s peculiar perspective: in order to attribute to babies such evil, he must also attribute to them a developed faculty of reason. If this is the case, St. Augustine is coming to his conclusion of the depravity of babies only because he believes a reasoning soul lies at the core of human nature; he is trying to assert, albeit in a roundabout way, that babies are fully human and full participants in the reasoning capacities common to all human beings. If this is true, we should consider that the young ones we encounter in our lives may reveal to us profound truths in their own ways of reasoning and relating to us.

My experience has certainly borne this out with my own son who is not yet a year old. I have been shocked on a variety of occasions by thoughts that occur to me through interactions with him. When I say this, I mean not just that I am reflecting on being a father or having him as a son and subsequently coming to novel conclusions; rather, my claim is that my own perspective shifts in observing how my son appears to see differently. In these moments, though he has yet to begin talking, my son speaks to me in such a manner that I am jarred out of perceiving things in my habitual ways. I am sharing these thoughts here with the hope of two possible outcomes: the first would be that I may be able to articulate what other parents have already experienced but not thought to formulate explicitly; the second would be to encourage those without children to look forward to the joys and revelations that become possible to us when we are gifted with children of our own. I will not tell you all I have observed but instead provide just three key thoughts that my son has revealed to me: the carefulness owed to consumption; that there is no inherent relation between responsibility and guilt; and the radical uniqueness of being.

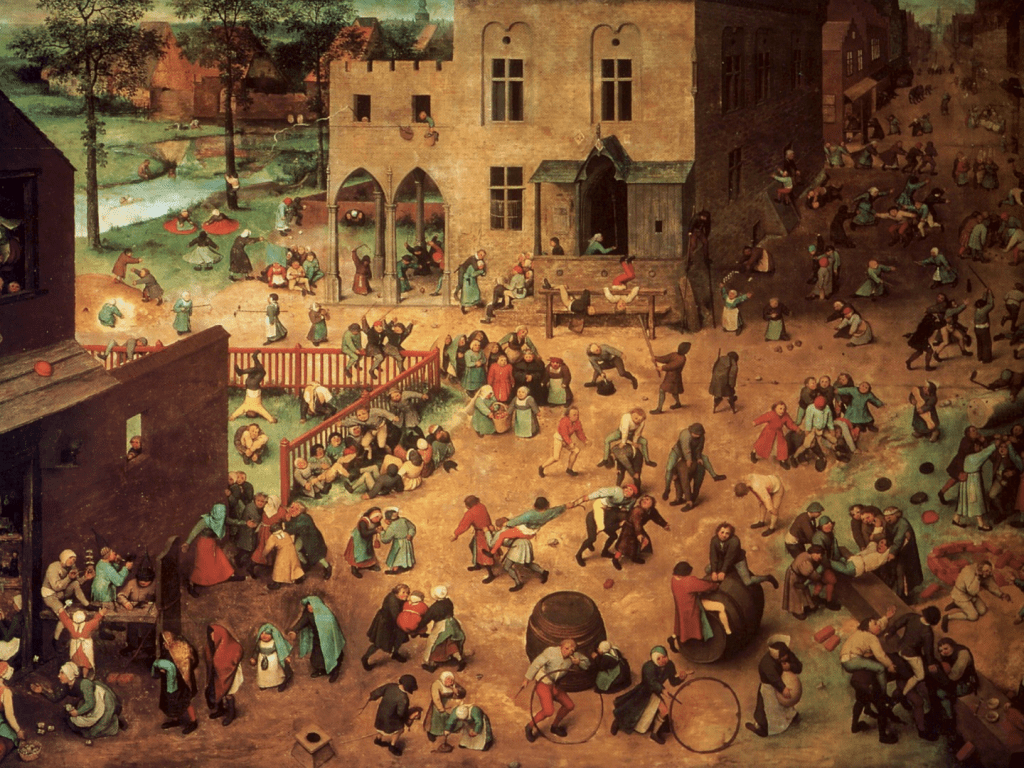

Per the way domestic life has ordered itself in our household, I tend to rise early with my son; this means we get a couple hours together, just the two of us, that includes a fairly regular routine. We get up and get changed, pray for a little while, play (usually with many toys), eat some food, read a short book or two, then get ready for morning nap – all in all, taking about two and a half hours. My son’s first lesson for me takes place during these morning ‘hangouts.’ The joy of breakfast has been to see the manner in which my son experiments with a previously unknown food every few days; mornings are a time when he tries many new fruits, the odd new vegetable, and new breads or grains. He must eat a given food about four or five times in order to become accustomed to it. During this process, every day is an inspection: he grabs the food to examine it closely with his hands, looking it over carefully with his eyes, then gradually bringing it to his mouth for a long chew and taste, before finally swallowing. In each case, this is done with intense focus and discernment; now and then, this will even recur with a known food if it has been a week or two since he last ate the same item.

To be clear, this sort of deliberation is not always present – during playtime, he immediately shoves toys (and whatever else he can find) into his mouth without a second thought. Nevertheless, when it comes to things he is evidently and intentionally consuming, the process becomes far more attentive to and mindful of what he is handling. The fact that he seems to know there is a difference between consumption and mere play is itself intriguing; what is more is how he is particularly careful in the former and not in the latter. Strangely, this is precisely the opposite of how I frequently operate in my own life. The things that are more recreational or, let’s say, inessential are those things to which I am frequently most attentive. The essentials – like food, drink, and sleep – I tend to let slip by the wayside. He lives in an entirely opposite manner, as if he intuits where his strongest attention ought to lie, and I have begun to rethink the way I look at how I injudiciously mix up what should command my attention more or less. In observing him and matching his rhythms to have a sustainable schedule, I have needed to rethink what I am prioritizing in my own habits: the essentials must be recognized and treated as just that – essential.

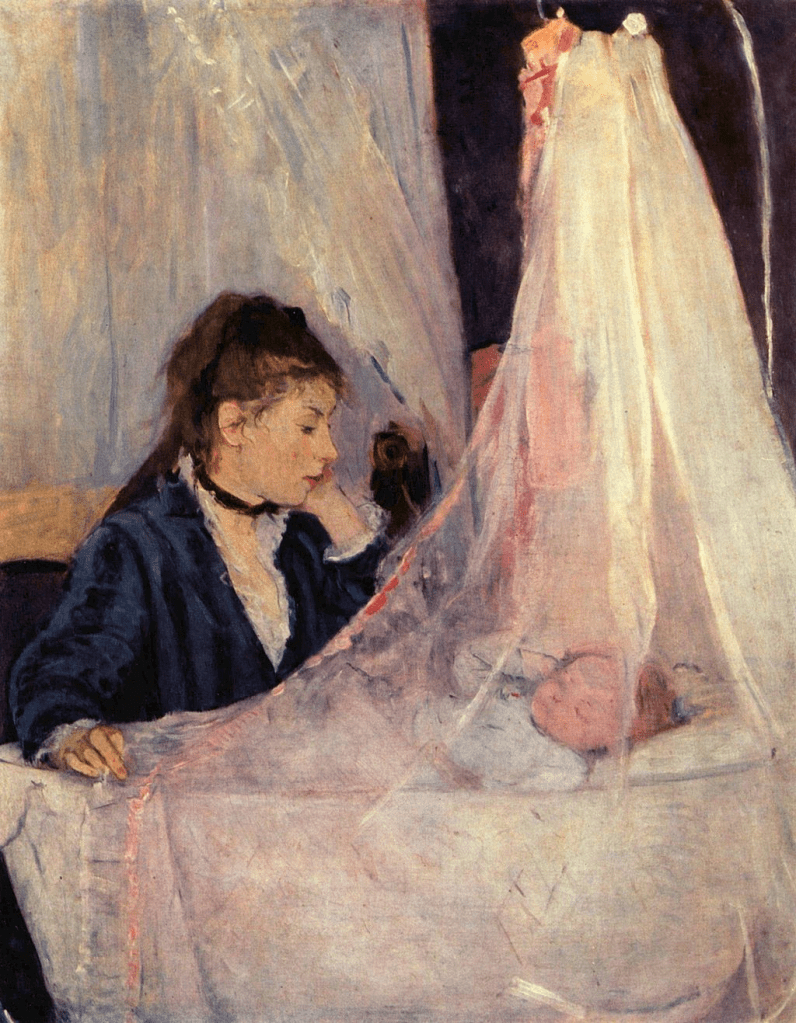

We may now go on to the second lesson. An awful stage that has recently beset my son is horrible teething pains. He already has several teeth, and more seem to be breaking through soon (at least we hope so…). Especially in the evenings and nights, these pains can be bad enough that neither I nor my wife are able to ease him entirely; calming him takes strenuous and lengthy efforts that are frequently quite burdensome. I am more than aware that this is a common stage for many children, and we are hardly the first parents to be enduring such trials. What is often so troubling about these situations is that there is nothing one can do as a parent, at least with any surety. One must merely stand by and try to support the child in enduring the pain of their teeth coming through the gums. Despite that our son does not entirely calm by our mere presence (which is usual for him to do in most other cases), our lack of presence would surely make the situation far worse; he wants at least one us, sometimes both, to be right there with him as he endures the pain. As a parent, there is a clear duty perceived here that one must respond to what the child is enduring, as much as there is nothing really to be done and the situation was impossible to avoid in any clear way.

This may seem obvious to others (I hardly claim to be wise in anything), especially those who work in various ‘care’ industries. But this is very different from most other circumstances wherein one must ‘take responsibility’ today. When working in a job, playing on a team, participating in a club (especially of a competitive nature), or even living out a marriage, the notion of taking responsibility is frequently tied up with the acceptance of guilt. This need not be taken in a dramatic sense; the cook at McDonald’s (which I was) can forget the extra pickles on a cheeseburger in the hurry of a dinner rush – his ‘guilt’ is hardly world-shattering for anyone, but he is guilty nonetheless. In relating to my teething child, however, there is no sense of guilt. In these moments of intense pain, he never looks at me as if it is my fault that he is in pain; nevertheless, he does stare at me with expectation. He demands a response without ever attributing guilt to me. My son is teaching me that there is no necessary connection between guilt and responsibility – indeed, I think that I (and maybe we) are blind to this because we live in a world of which we are so deeply in control. Responsibility seems inherently entangled with guilt because all things appear to be the products of our own activity (jobs, academics, targets, championships, marriage, etc.); in such circumstances, taking responsibility only matters when we fail in those projects. Parenthood (and, frankly, much more) becomes about asking what a situation that is ultimately beyond my control demands of me in a way that is foreign to other common affairs of contemporary life – and it is good to be reminded that I should reconsider what is being asked of me (in both mundane and profound senses) regardless of whether or not I am guilty of anything.

The final lesson I have received from my son is a recent one, and it is the one that has struck me most deeply. The manner in which it came about, however, was profoundly banal. I prepared a small snack for the two of us which included some ordinary crackers. I gave one to him and took another for myself. In response to this, my son immediately dropped his cracker on the table and reached for mine in expectation (he wanted to share, which he has recently begun to indicate via various cues). Admittedly somewhat annoyed, I picked up his dropped cracker and tried handing it to him again; “Look, Bubba, these are the same thing, but this one is for you.” No use. He acted like I did not even have ‘his’ cracker in my hand and was still reaching for ‘my’ cracker that was still in my other. I acquiesced and gave him ‘mine,’ which he gladly accepted and munched on with great vigor. I shook my head and thought, ‘What a silly kid’; I then, somewhat weirdly, looked very closely at the two crackers – one in his hand, the other on the table still. They were not, in fact, the same.

The crackers were certainly similar, but they were also not the same in rather obvious ways. One cracker was slightly larger than the other; they had different grooves and seasoning patterns, affecting their colour; one had been in my hand, the other was actively released. They were obviously different – and my son’s lack of clear, abstract categorization made this obvious to him. In his mind, ‘cracker’ means nothing; rather, he is perceiving two discrete objects coloured by their various divergences. Now, we aged-people may note that abstractions are useful for our thinking, communicating, and maybe even getting by (it is best that we do not freak out about which apple to select for breakfast; assuming them to be the same makes choice much easier in it appearing arbitrary). At the same time, however, such abstract thinking can make us insensitive to our circumstances when taken too far. Evidently, we know that there are many individuals who fall under singular designations: we know a variety of people who are labelled woman, man, wife, husband, sister, brother, mother, father, daughter, son, adult, child, etc. etc. But to know such things is never truly enough; what is far more important is to know my wife or my sister, but this must be specified with a much more particular name and idea. My son, in the absence of clear, general categories of cognition, is able to see more lucidly the particularity that is inherent to yet so often avoided among all our goings-on. He determines the number of the stars, He gives to all of them their names.

My son confronts me in a most peculiar way: he is evidently a part of me and an outgrowth from my very being, yet in these moments I am confronted by a profound other. He sees in a way I do not; he reaches in a manner that would never occur to me; he smiles when I forget I, too, can do so. For a little boy who (sometimes frustratingly) says nothing, he speaks a great deal. If only I could tell him of his wisdom, but then I suppose I would need to begin worrying about his humility.

I would tell the author how wise HE is, but then….

LikeLike