A colleague of mine often playfully chides me for being too analytical about what words mean – assuming that one can ever ascertain this. What my friend is also commenting on is the manner in which I am liable to presume that I do not understand what a given word means when speaking to various people. I frequently assume that words today have deeply unstable definitions, and this is (unfortunately, for a political theorist) especially so for many words that are central to our political discourse: ‘democracy,’ ‘liberalism,’ ‘freedom,’ ‘rights,’ ‘capitalism,’ ‘socialism,’ etc. This could be a much longer list, but I will keep it brief here. Alas, despite that I am playing into my friend’s hand, I think it is worth reflecting upon another word that has become rather distorted, though it is not a word of specifically political importance (though it surely has indirect effects). The notion I have in mind is ‘subjective’ or ‘subjectivity.’ Anyone in the anglosphere today is probably aware of this term and hears it used with some frequency, and I think that its (ab)use should be outlined in some detail.

In usual discourse, this term of ‘subjective’ is often used to defend or explain a specific judgement; ‘subjectivity,’ understood as someone’s personal deliberation and decision making, is claimed to legitimate whatever judgments individuals are making. For example: “Is chocolate or vanilla ice cream better?” Whatever answer we may give is often provided and deemed legitimate by appeal to ‘subjectivity’ – everyone has their own answer, and each answer is validated by the fact that it is the person’s judgement. If my wife chooses vanilla while I prefer chocolate, our different preferences are ‘correct’ because they are our judgements. I cannot say she is making the ‘wrong’ judgement because ours do not concur – we simply have different tastes, and it makes sense that we should be allowed to act on those preferences when selecting our ice cream flavours. Of course, this example is innocuous enough, but this sort of reasoning seems to be continually applied to ever more realms of decision-making. I think a most clear example nowadays is that of sexual ethics; whether one wishes to practice chastity, engage in polyamory, pursue various fetishes, etc. is taken to be a ‘subjective’ concern – this is, in my view, the only way to make sense of ‘consent’ as the ultimate arbiter of sexual conduct.

I believe, however, that this is simply a misunderstanding of how our moral deliberation works and what subjectivity really signifies. No doubt, to refer to subjectivity as being the mediating reality in which discernment occurs is hardly debatable. But, in this sense, there is nothing that is not subjective. Various colloquial ways of speaking may, however, be causing much confusion here. For example, ‘objectivity’ is not the opposite of ‘subjectivity,’ despite that many people speak in this way. Whatever we may call ‘objective’ is, in fact, a description of the status of a given idea or statement that can only be ascertained through intersubjectively mediated judgements. No one should claim that science is devoid of subjectivity; rather, the scientific method is a manner of constraining subjectivity in such a way that we can ascertain certain ‘facts’ in common. This holds for other forms of enquiry as well: historical, juridical, forensic, etc. In this way, the ‘methods’ of these various ways of thinking is what provides their claims with any sense of veracity. One cannot appeal to his mere ‘subjectivity’ to claim that he knows Sir John A. Macdonald was the first Prime Minister of Canada; he must have recourse to some form of justification such as history books, government documents, common opinion, etc.

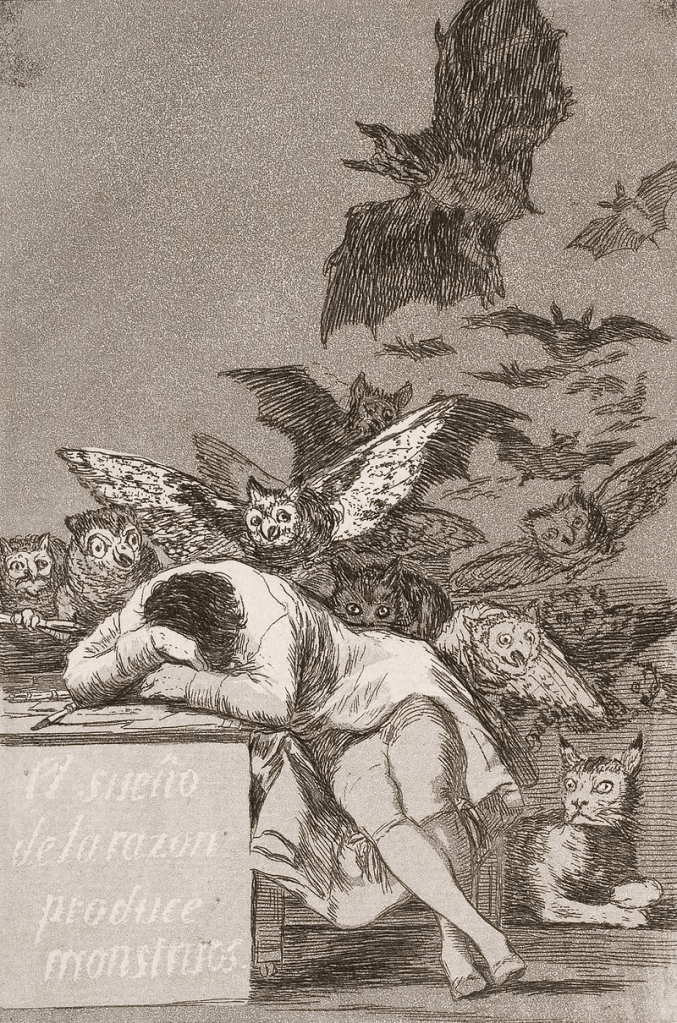

I think that we now need to return to the above examples that I provided: ice cream and sexual activity. Claims of these sorts are evidently not like the various forms of enquiry I just listed off. They may be more related to what we consider ‘taste’ and ‘morality,’ respectively – but I believe that these are, no less than history or science, genuine forms of thinking that have their own criteria by which judgements can be made and interrogated. This is made evident by asking anyone why he or she is choosing a given thing or course of action; they may start by saying, ‘Because I like it,’ but this can then be answered with the same question again: “Why?” I quite appreciate a careful use of italics provided by Michael Oakeshott in his magnum opus, On Human Conduct: there is a difference between explaining something with ‘These are my thoughts’ and ‘These are my thoughts.’ The understanding of subjectivity I laid out above is highlighted by emphasizing ‘my,’ but this is no explanation at all. The only relevance of ‘my’ in a given judgement is that the thoughts occurred in a given person. Obviously, my wife’s thoughts are much more important to me than a stranger’s, but this does not mean that a given line of reasoning is justified by it merely being hers (though I may be tempted to think this way now and then). Subjectivity, then, is a description of thinking that may localize where or in whom it is occurring, but this is not itself ever sufficient to justify the claims that may be arrived at subjectively – for that we must defer to the actual reasoning undertaken by the person in question. The nature of this reasoning, then, becomes the crux of our concern. We can return to the idea of there being various ‘methods’ or forms of thinking and recognizing that even ‘taste’ and ‘morality’ have this. There is a reasonable claim to be made, however, that either this method has been destroyed or lost and its lack of presence in our current thinking explains why subjectivity has come to be used as a justificatory notion – we do not know what else to invoke to justify ourselves.

Just this sort of pessimistic claim about our capacities for moral reasoning was, in fact, articulated quite forcefully during the 1950s through 1980s by three philosophers from the Anglosphere: Elizabeth Anscombe, Philippa Foot, and Alasdair MacIntyre. Each of them argues, in different though complementary ways, that the nature of our moral language and reasoning has become so confused and untenable because the formal nature of this kind of thinking has been destroyed. Without an understanding of what moral thinking is meant to aim at and may legitimately invoke, there can be no genuine moral inquiry. More concretely, they all argue that the purpose and idea of a fulfilling human life has simply been lost. Without some kind of image of what a full life entails (even if sketchy and undetailed), the specific decisions that we make cannot be substantiated. We should note that the histories these philosophers provide tend to suggest a coincidence between the loss of this vision and the loss of religion; say what you like about specific religions, they tend to have heroic or emblematic figures that ground their claims and reveal what a good and fulsome life looks like: Christianity has Jesus, Buddhism has Siddhartha Gautama, and Islam has Muhammad.

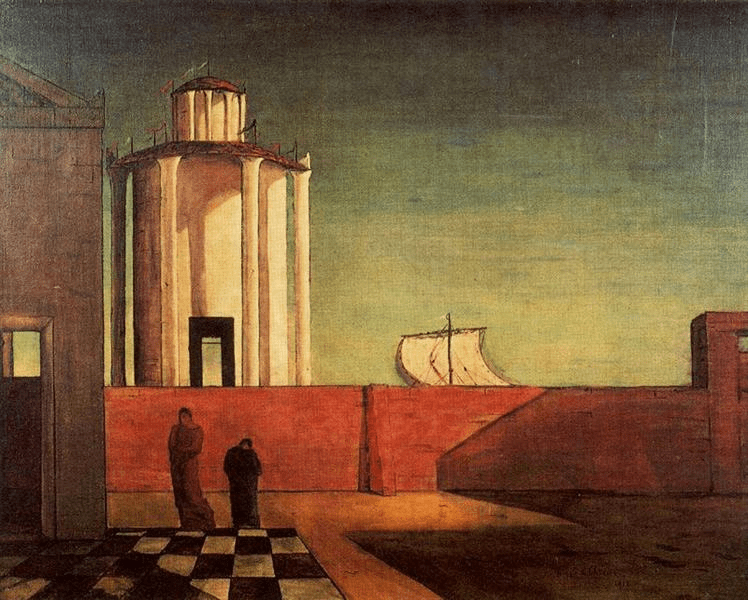

There is, no doubt, a great difficulty here: how would we decide between the images I just invoked (knowing full well how many more there are)? How are we to decide between the Buddha and Jesus? Does this not merely throw us back upon the claims of subjectivity to choose between these fundamental frames? The answer, briefly, is no. One does not merely adopt these positions in some ad hoc manner and then begin to reason morally; rather, one will compare the claims of these religions or ‘philosophies’ with the various aspects of their own lives. What are the fundamental problems we face in our daily lives? What do I envision coming in the future? Perhaps most profoundly: what am I supposed to do about the inevitability of pain, suffering, and death that are rife in the human predicament? These religions or ‘philosophies’ offer provisional answers to these kinds of questions that we find ourselves in and allow for some semblance of a path through them; this is not to say that they eliminate personal, circumstantial judgement, but that they offer a framework in which such judgements can be deemed more or less reasonable. The specific judgements and the frameworks are always operating in tandem and reflect off one another.

Following in the wake of these philosophers like Anscombe, Foot, and MacIntyre, we may begin to more exactly understand my objection to how ‘subjectivity’ is used: human life is not simply discordant due to irreconcilable differences between people’s perspectives, and to suggest this means that any moral judgement is in fact no judgement at all. Holding subjectivity as the ultimate arbiter of moral claims is the facile and untenable view that we might term ‘subjectivism’ or ’emotivism’ – the latter being MacIntyre’s explicit, (in)famous enemy. The true issue, which we can see when we dismiss subjectivism and emotivism, is that moral judgement requires a sense of direction, a sense of ‘the good,’ and this cannot be left as a vague notion (even if every detail is not fleshed out). Why, then, is our moral reasoning so fractured? It is not because human beings are inherently at odds with one another about what should be done (in the manner that crude readings of Hobbes or Nietzsche might suggest), but because we lack a common vision and – in many cases – any semblance of even a personal vision. If my contention here is correct, contemporary moral reasoning is plagued by our lacking understanding of what should be done for ourselves and those around us at the level of what a fulfilling human life looks like. Without any notion of what should provide us with such an answer, we can never answer two questions of the utmost importance: What should I do, and what should we do? Given that this is a question of vision, we might ask these questions in an even more provocative manner: Who am I, and who are we?

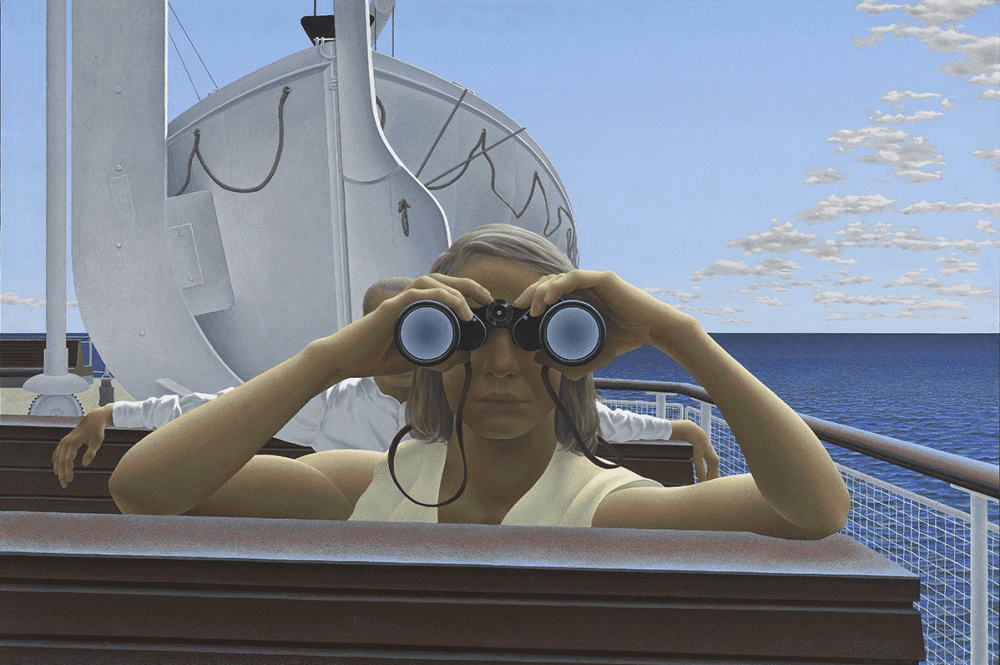

Of course, doing this in practice is a profoundly arduous task. Nevertheless, its difficulty (or seemingly practical impossibility) should not suggest that pursuing it is foolish – indeed, requiring absolute achievement in any form of inquiry (like history or science, too) would thwart all thought and activity. For now, we can at least provisionally acknowledge that recourse to ‘subjectivity’ is simply inadequate and perhaps even damaging. I will admit that I think few people really believe and act out the notion that the mere subjectivity of a claim can ever truly justify it. Nevertheless, I have noticed that people are liable to slip in and out of this sort of language when it is advantageous for them, and this has become a prominent enough practice that people are beginning to genuinely believe it. (As a brief and personal aside, when I began teaching university students in 2019, about half of my students thought morality was ultimately “subjective’; now, I will have only 1 or 2 students out of every 25 to 30 that will resist such a description of morals. Intriguingly, however, none of them speak or argue in specific instances as if they believe these erroneous claims of subjectivity are ultimately true.) In considering subjectivity more fulsomely, I hope to have provided a better understanding of what it is: a descriptive aspect of all human affairs, but one that justifies none of them.

I think people are coming to understand that subjectivity requires a sense of direction, but we are still at the stage where the direction is arbitrary; it is at the whim of subjectivity. Kierkegaard made the case that “truth is subjectivity,” but at the same time he held that there was a right way and a wrong way to be subjective, and a clear analysis of our subjectivity as a predicament would point the way to the truth to be found in subjectivity. Today this analysis is not being performed. People feel free to believe what they want to believe — the postmodern condition — but lately, forsaking the irony of postmodernism, they feel the burden to believe something with sincerity — what has been called the metamodern condition. But then they feel that it’s OK to be sincere about a belief arbitrarily, or anyway based on inadequate reflection — based on whatever makes them feel good, rather than the existential reflection involved in “knowing thyself.”

LikeLike

Ah, yes – believing in belief, so to speak. Ultimately, that too will prove vacuous. But how long will that take?

LikeLike

Things will have to get worse before they get better. On the other side of metamodernity I would expect a better sense of story, a more powerful sense of presence in the world, and a sense of getting along in a living reality beyond the human. But first the old structures, built on our experience as isolated atomic individuals negotiating a meaningless void, will be propped up and braced by desperate means, until despite all efforts they collapse of their own weight. To the extent that our supposed perfect freedom is in tension with reality, this process will be accelerated.

LikeLiked by 1 person