In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle discusses the nature of friendship and its profound (and perhaps near primary) importance in a fulfilling human life. This claim in itself could and has been the subject of much discourse, but his development of this topic provides many other ideas that are worth pursuing in their own right. One such detail of his writings that has occupied me is the different sorts of friendship that exist; for Aristotle, we can separate friendship into three distinguishable though not discrete forms: friendships of utility; friendships of pleasure; and friendships of the good. In brief, each of these connote a specific way in which a kind of love, φιλία (filia), develops between two people – this is the meaning of ‘friendship’ itself. The other terms, then, indicate the reality or commonality upon which a given instance of love between friends is grounded.

When Aristotle speaks of friendship, an ‘individualist’ reading of the topic is not unreasonable. He tends to speak of friendships as merely one-to-one relationships, what we might consider partnerships, that take on one of the characters that we noted above. This framing is perfectly sound in its own right, as friendship can only exist between individuals; the idea of being ‘friends with a group’ as such is rather incoherent. However, this emphasis on the individual dimension may leave underexplored the broader communal contexts in which friendships arise. (I will have to be forgiven for not taking seriously the notion of ‘online’ spaces – this could be argued for, but would take me too far afield of what I wish to discuss here.) To be clear, I do not think Aristotle simply neglected this aspect—rather, it was not his focus in the surviving works. And I am generally wary of critiquing omissions unless they are particularly egregious. I mention this only because it opens space for further reflection in directions that may prove fruitful.

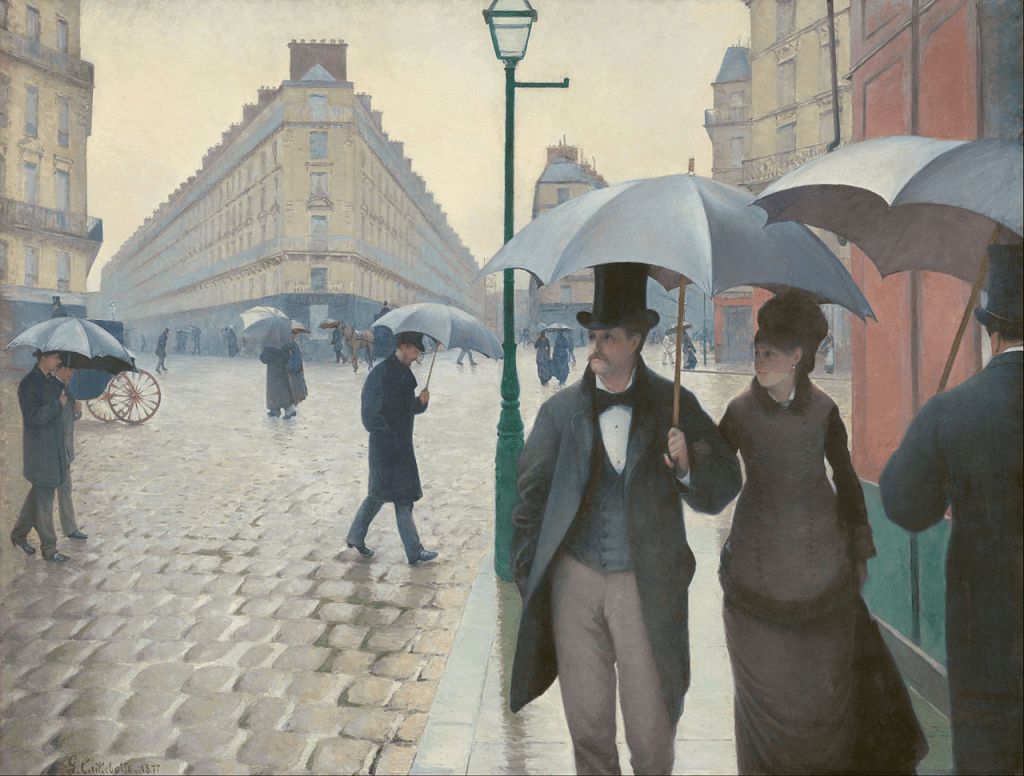

I think that what Aristotle provides is a solid point of departure for reflecting on the manner in which various communal spaces can act as the mediation points for the different kinds of friendship – and I want to, perhaps provocatively, suggest that the spaces that once existed for friendships ordered toward the good have largely been lost. I do not think the same can be said of friendships based on utility and pleasure; those appear to have a good enough footing even today, though there could be other more complex considerations of how even those have corroded in recent centuries – though that is a different topic. For now, I want to reflect on how the various institutions and groups of which we are frequently engaged act as mediation points for different sorts of friendships to develop and that these loci must be preserved in themselves. If this is not done, the differing forms of friendship, especially the sort that is ordered toward the good, become radically difficult to foster and maintain.

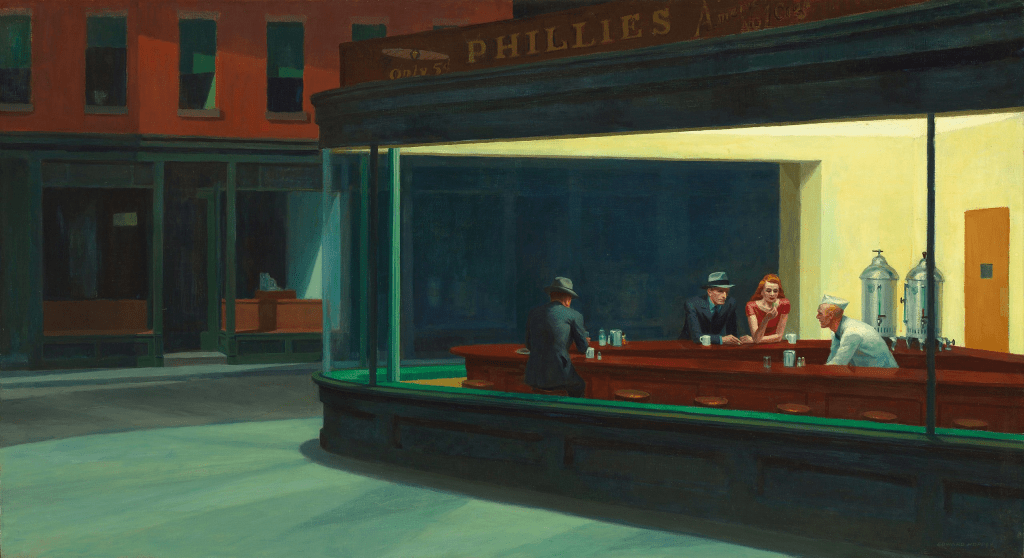

To begin with the first of the different types of friendship Aristotle considers: in simplistic, contemporary terms, we can understand what Aristotle means by ‘friendships of utility’ as ‘work friendships,’ or the way that we may refer to someone as a ‘work friend.’ When using these terms, we are typically referring to someone that we work near at the office and with whom we get along well enough – but the relationship has virtually no existence outside of the workplace. Aristotle also would have meant something like the cordiality that emerges between people who are doing business for mutual benefit (perhaps a grocery vender and his local supplier). What is key here is that the kindnesses exchanged between the two parties is not based on an interest in the other person for its own sake but instead on maintaining the relationship between them that accrues mutual benefit on a regular basis. We need not necessarily be cynical about this, but we should also be honest about the fact that there are many people with whom we have worked but are unlikely to ever contact beyond the circumstances of our workplaces; these are necessary but hardly life-giving relationships. I will conjecture that most of our relationships actually take this form, especially in our heavily transactional manner of living – a claim arguably tied up with the characterization of our age as ‘capitalistic.’

‘Friendships of pleasure’ are precisely what they sound like: the sorts of relationships that are predicated on the common enjoyment of some given good or activity shared by two or more people. This need not be taken in a hedonistic sense, though it can certainly take on that form as well. When referring to such a ‘pleasure,’ we could be thinking about something quite healthy like the common enjoyment among some middle-aged men who join a flag-football league to get a little running in; conversely, we probably know (or have been) the sort of person that has friendships based purely on drinking and partying. Other examples could be membership in various clubs or volunteering organizations, though even some workplaces might reach to this sort of status too. (I would say my own experience within the university is that it is a business, but one that fosters friendships around a common pleasure of learning and discoursing as opposed to mere transactions.) We might conceptualize these sorts of friendships as a slight improvement upon ‘friendships of utility’ as – unlike with utility – a common pleasure does reveal something about oneself that is being opened up to another. Moreover, we can imagine how such a limited sort of revealing and commonality may stimulate us to become more fulsomely familiar with those whom we are sharing in such activities. Nevertheless, this opening up indicates an extension beyond mere pleasure.

Finally, we arrive at those friendships that are ordered toward the good of each friend as such. This is a much more difficult and experientially elusive form of friendship. This type involves an intimacy and knowledge of the other that builds into a genuine regard and concern for his or her good in a fulsome sense; to be a true friend is to desire the best for the other on their own grounds – not because it redounds to my benefit or because we have some common interest to enjoy together. This is not to say that an actual, lived friendship is ever this alone; typically friendships emerge and are sustained by having lesser forms of commonality such as utility and pleasure. The difference is that the affection and attention shown cannot be reduced to those factors in a ‘friendship of the good.’ What is even more difficult to describe are the contexts of such friendships. Unlike with utility and pleasure, these do not seem to have a clear place in our contemporary culture. Most people today who have genuine friendships of this nature have only stumbled upon them by circumstance and fight hard to maintain them through deliberate effort on an individualistic basis.

My conjecture would be that there are two places, at least in the history of Europe and its offshoots, that have approximated stable loci for ‘friendships of the good’ to emerge: the ἐκκλησία (ecclesia) and the πόλις (polis), or the Church and the City. In each case, these were places where people could meet and encounter one another with no ulterior motives of either utility or pleasure. Instead, there would be considerations, in either context, simply about the nature of the good life and ordering ourselves together in that direction. Now, this is not to say that the Church and the City are comprised entirely of people who are all profound friends with one another and deeply concerned with the development of every other individual’s good in detail. Rather, I believe that the very fact that these sorts of institutions were not ideally ordered toward the gratification of some immediate, transactional need or the mere enjoyment of a common delight allows for an open space in which the ‘other’ is more accessibly encountered. In such an environment, that ‘other’ can become the focus of one’s attention and affection. Naturally, the mere membership in a Church or City is not sufficient for this sort of friendship and there have been many instances of both these phenomena that have failed to be such open spaces; but these loci lacking any real prominence in our current societies surely makes the pursuit of such agapeic friendships supremely laborious and improbable.

If, then, we agree with Aristotle about the need of fulfilling friendships – as I am certainly inclined – we must recognize what is needed for friendships to be fulfilled. We need to have spaces in which all that is pursued for the sake of utility and pleasure is pushed aside; this is not because utility and pleasure are evil (they are surely not and have their legitimate places) but due to their tendency to inhibit our attention from focusing upon the person as such. We need to reconsider the manner in which our chosen spaces of interpersonal engagement, encounter, and community either do or do not foster this capacity to allow ourselves to become lost in the story of one another’s lives without ulterior motive. In my view, Churches (or whatever form of temple one may be inclined to entertain) is the most relevant and fruitful option for contemporary life. Though even such ecclesial environments have surely not remained immune to the effects of a transactional and capitalistic world, they retain a level of removal from it – a place deliberately set aside – in which transcendent and profound realities are encountered and contemplated. On the other hand, the City may still be a viable option, insofar as it allows us a place to share and foster what we think our shared life should look like; this has, however, often been overcome with the concerns of utility and pleasure, which makes me somewhat pessimistic about its opportunity. Nevertheless, I have hope that someone with a proper sense of the polis, the meeting place for such self-revealing and cooperation to come forth, may instill a renaissance by looking to local politics as a place for encountering and appreciating one’s neighbour more profoundly and personally.