As I have indicated in prior blog posts, I enjoy finding etymological connections between words and thinking through how those connections might inform our living. Thinking about terms that have the same origin might inform us about how others have thought and even the way we implicitly think as we use our languages (usually unreflectively). A great example of this for me is the pair of conversation and conversion. They both come from the Latin cum, meaning ‘with,’ and versare, meaning ‘to twist.’ We can contemplate how conversation involves a ‘twisting with’ the thoughts and speech of an interlocutor, and this is no less true of when we are ‘converted’ to think something new as our minds ‘twist with’ a new way of seeing the world – whether this be in the profundity of a religious conversion or merely in the mundane realization of a better way to slice an onion. This shared etymology suggests to me two things: conversion is impossible without some level of conversation, and conversation is always a kind of conversion – even if only in subtle ways of which we are often unaware. To see this connection can radically change how we perceive and live out both these words.

Another pair of etymological siblings recently struck me: communication and communion. The latter is a word that has perhaps fallen out of fashion, but it nonetheless has a salient meaning. They share the Latin root communis, literally meaning a ‘coming together’ in the sense of sharing a common experience. In our English terms, then, the etymological origin is still present and active: communication indicates a kind of ‘coming together’ in our ideas through discourse by whatever means we have access; and communion connotes the idea of being in some kind of association that actively communes, comes together, to perform something as one. (Not irrelevantly, it was common in prior decades for Catholics to refer to participation in the Mass [or Liturgy] as ‘communing’; this is indicative for the nature of communion, which is critical for Christians – if one is interested in the sort of Christian someone is, he may ask, “Who are you in communion with?”) What strikes me about this pairing is a perhaps problematic reality that we, today, know quite well but which has been unknown within nearly any earlier civilization: what happens when communication and communion become disentangled from one another?

The novelty of contemporary life that I am referring to is evidently that of the incredible communication technologies that were unknown two centuries ago but we ostensibly cannot live without today. This very blog can reach anyone in the world; we call, message, and share across the world at speeds that are practically instantaneous. We are now confronted by questions and concerns at a global level, which also puts us in the peculiar position of needing to have a perspective on things we barely encounter and hardly understand at a practical level. Moreover, our online spaces connect us with thousands or even millions of people who have the same interests as us, are developing similar opinions, and using similar terminology to express themselves. Now, of course, all these goings-on can be conceived of as kinds of communion. I, personally, live in a different city than much of my family, and having the capacity to call with them sustains our sense of commonality and connection. Nevertheless, I think we also know well that many of the people with whom we engage online are scattered around the world, or at least a continent or country. In this way, the nature of our ‘communions’ within these online forums should be understood as radically different from the sorts of communion known to anyone who lived before the advent of the internet (or, perhaps, even the telephone).

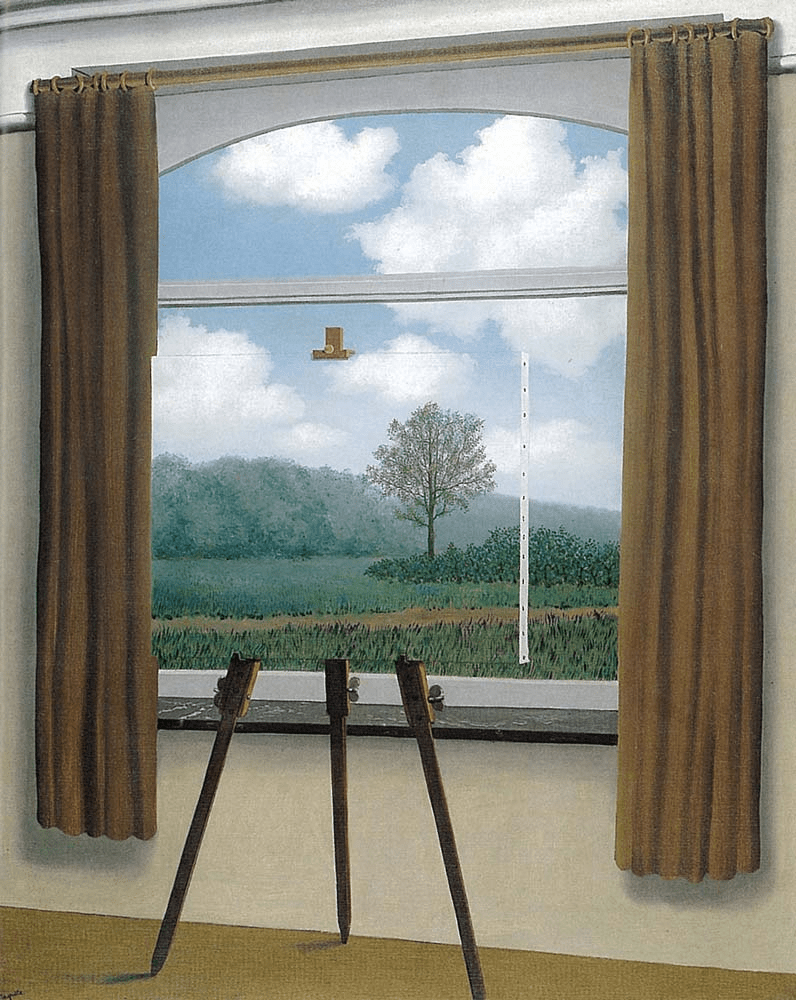

We must understand that all language is a practice produced through the verbal intercourse of at least two (but evidently many more) human beings. Despite what a dictionary or grammarian may indicate, the rules and components of a language are not true in some a priori sense; they are only true insofar as a given lexicon and certain syntactical norms are widely used and recognized. Of course, this makes understanding the ‘proper’ meaning of a word rather tenuous – of which there are many examples; drawing from my experience as a teacher, I have noticed the slippage of a word in recent years: ‘unfathomable.’ This word has come to be used by many of my students as a synonym for ‘incomprehensible.’ The latter word means, literally speaking, something like ‘unable to be grasped together.’ This is not, however, the meaning of unfathomable – at least historically. To ‘fathom’ something was, at one point, a naval term relevant to measuring the depth of a body of water. To say that something is ‘unfathomable,’ therefore, is to say that it is of such a depth that it cannot be known. We can understand how this might then be analogically applied to certain ‘philosophical’ notions, such as God’s nature – they are to ‘deep’ for our limited reason to fathom. In this sense, I grant that all unfathomable notions are also incomprehensible, but to say that everything that is incomprehensible is unfathomable is to be confused. What is unfathomable is also incomprehensible because it exhausts or transcends our powers of reason, yet something could be incomprehensible because it is illogical or a contradiction – which is quite easy to fathom.

It seems, however, that I am likely fighting a tide that is hardly worth resisting. Most of my students think that this use of unfathomable is fine, and this may be due to their lack of familiarity with the origins of these terms coupled with a conventional way of using language as it seems fit. If many of us are detached from the settings that brought about a word like ‘unfathomable’ (not unreasonable for a bunch of in-land, city-dwelling kids), we might begin to expect that its definition would warp to match other terms that are similar and more fundamentally lodged in our lexicon (like, in this case, ‘incomprehensible’). What this indicates is that there are at least two profound influences on language that should be considered beyond the early advent and development of a word: (i) how is it used in daily conversation, and (ii) how do the contextual circumstances of a given conversation affect the manner in which a word is used? If I were to try and encapsulate these considerations in a single term, I would use the term ’embodiment.’ Asking how a word is ’embodied’ is to ask not only about its origins in early use but to then understand how it has continued to be enfleshed in conversations which are subject to the modifications of specific, circumstantial conditions.

A logical corollary of this claim is that there is no such thing as a language that is acontextual, and all language develops and maintains its meaning precisely by being used in both continuous and innovative ways. Language is always about something, and our experiences are what tie together our common use of a language and allow for it to develop; if this were not so, I cannot understand how one would be capable of picking up a language in the first place or how that language would be able to transform. It is in this sense that I think the shared etymology of communication and communion come together so clearly. Our communication develops in a language that remains intelligible to us through our shared, communal, use of the language. We can quickly understand how this fact is what allows for dialects and subsequent languages to develop: they are merely customary updates to a common language that eventually arrive at different enough uses (often over wide timespans) that they can be distinguished and categorized.

Curiously, however, this also means that our language can become obscured from those around us if we are engaged in communally uncommon or eclectic pursuits. If we have access to some other manner of writing and speaking, the habits of a foreign manner of speaking can become prevalent in a place they seemingly shouldn’t exist (like how North Americans who watch a lot of British programing begin using words like “bloody”). Something I have noticed in myself is that my lexicon and syntax often reflects that of Englishmen from anywhere between five to fifteen decades ago. This is because I read a fair amount of philosophy and poetry from England during that time period. Such a peculiarity is found in my propensity to say “an” before words that start with an ‘h,’ even if the aspiration in my Canadian accent should suggest that only “a” is necessary. I do this enough that I have had people question why I do so, and I have provided this very explanation. Is this odd? Yes. But it is hardly destabilizing to my intended meaning and can easily be clarified with a quick switch back to a more normal idiom or expression.

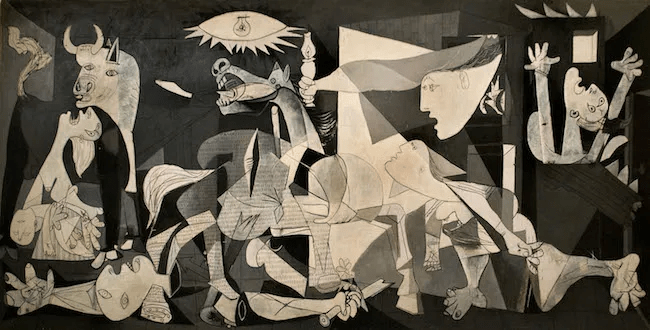

What intrigues me, however, is the manner in which technological communication has caused our immediate, proximate, embodied speech to become fractured and disjointed. As I noted earlier, we can now be connected to nearly anyone anywhere in the world – and often many of them all at once – with whom we can have a sense of instantaneous and engaging dialogue. We should expect, then, that these online ‘spaces’ should begin to affect the manner in which we communicate due to how frequently we can partake in them (for most people, this would be much more than how frequently they can watch British programing or reading English literature). I will give two concrete examples that I have noted of late. Because I am rather curmudgeonly despite only being in my late twenties, I have noticed that my sister who is over a decade my junior speaks in a manner that I simply cannot understand; this would be normal in that I am no longer ‘hip,’ but what I have noticed is that she defers to explanations of ‘online communities’ of which she is a part when I ask her to clarify her meaning. She is not just odd to me because she is substantially younger and spending time with a new generation making language their own; she is also peculiar to me because she participates in online discourses that can silo into niche categories from a local, embodied perspective, but they nonetheless get a broad enough conversation developing online because people from all over the world are connecting. The second sort of instances I have noticed is the fracturing of memes, jokes, and slang terms along what seem to be political lines. I attend and work for a university, so naturally many of my peers are some sort of ‘progressives,’ ‘Leftists,’ ‘radicals,’ or whatever other words you would like to use. Though sympathetic, I am not quite on board with such things; I tend to be a man without a party because I am something akin to a Red Tory (in the vein of George Grant, though he rejected that label). This allows me to float more comfortably between what is today spoken of (rather unreflectively) as the ‘political spectrum.’ I therefore see more ‘right-wing’ and ‘conservative’ content online, and I have noticed that many of my peers are simply unaware of much of this world. Thus, my online activity has caused me to think and speak in a manner that is sometimes opaque to my academic colleagues as I use terms and slang that they have not encountered or practiced using.

What strikes me about this situation is that all this technological communication never seems to offer genuine communion – and I think few people are convinced that it can. Even with our electronically saturated lives, we have not gotten around the fact that we come from a family, work with several people, walk past neighbours on our streets, and have an embodied presence that can express much about oneself. Something I have often found funny is how I can be taken aback by someone’s height upon meeting them in the flesh after having been acquainted online (especially for some time). Of course, there is much more that you can discover about another in-person: one might discover how a man treats the serving staff when they go to a restaurant together; we might observe how another walks down the street and either imposes himself so as to have others move or is more meek and gives people the right of way; we may note where our conversation partner’s eyes drift when our discussion wanes for brief moments as dialogues tend to do. Of course, all these things could equally be said about ourselves, and these lived realities are critical to being known as we are, and this is the essence of communion: to be known as we are.

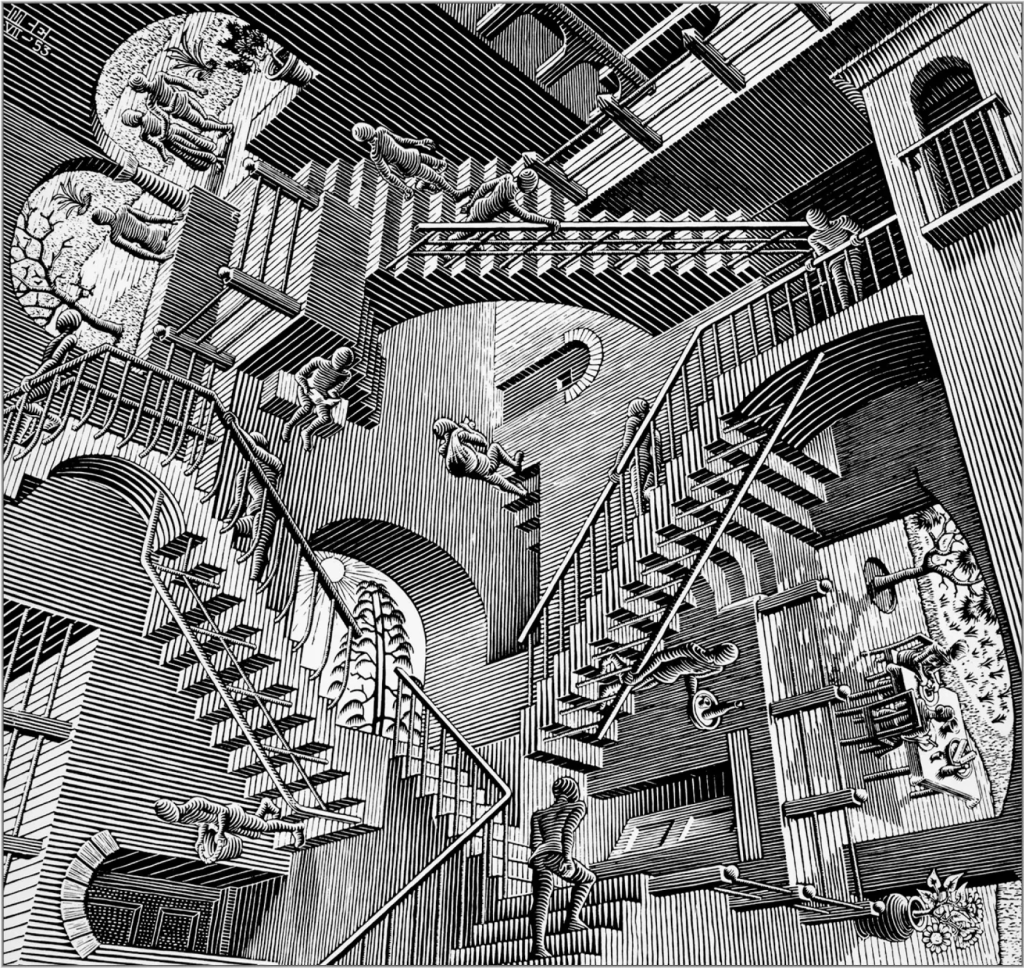

All of this has led me to a rather peculiar thought: where are my words? This is not a question I frequently meditate on; more often, I may think of what the words I am using indicate or how I am using them, but the notion of ‘where‘ rarely enters my consideration. This may very well be a new question, one that would have been impossible to ask just a century or so ago. But it now confronts us: Where are my words? Where am I imposing my words and how I use them? From where come the words that have begun to infect my own thinking and speaking? To return to that other etymological pair with which I began, conversation and conversion, I begin to ask if my speech and thought are twisting with – maybe even converting – to ways of speaking that are utterly foreign to where I am. I am forced to consider how I may be changing into something foreign to my present place, and – even presuming that this transformation is toward something truer and clearer – I must ask myself whether I want to become something that no one around me can truly understand. Moreover, we may ask if this is happening to all of us simultaneously in our siloed, online algorithms; are we all beginning to speak more idiomatically than ever before and fracturing our ability to know one another? In this sense, it seems that the technological influence upon communication and its effect on our language is developing so as to rupture our sense of embodied communion; my words are no longer with me, embodied in my daily life, but saturated with the ephemeral, online world. But, given their etymological kinship, we may wish to reflect: what happens when communion and communication are no longer intertwined with one another? Will either survive such a transformation?

Because of this fracturing, I have noticed that people tend to be cautious in initial encounters and use idiomatic phrasing to determine whether a person is in their communion before opening up. There is an increasing presupposition that most people one meets are unlikely to be reliably in the correct group, unless some noticeable marker or overwhelming stereotype is present.

LikeLiked by 1 person