Now and again, one comes across people who are dismissive of what have frequently been termed the ‘soft sciences’: sociology, psychology, anthropology, political science, and (for some, though there is more debate on this) economics. The main problem in these fields is that their findings are typically subject to human responses performed in whatever manner is relevant to the form of enquiry in question; this is juxtaposed with other fields termed the ‘hard sciences,’ like biochemistry or astrophysics, that study phenomena that are hardly affected by human volition. This then leads to further issues like replicability, but the most fundamental problem is a question of what precisely the soft sciences are providing with their various theorems and findings. A sociologist may find that divorce rates in Canada have been steadily on the rise, and he may point to a number of variables that seem to be affecting that output: greater economic instability, lacking religious sensibilities, and new understandings about the merely contractual nature of marriage becoming common. Yet, what precisely does one take from this? How would one factor this into his life practically?

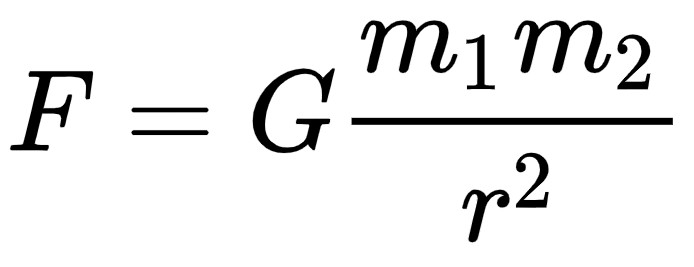

Most simply, I believe that the ‘soft sciences’ need to be juxtaposed with the ‘hard’ in order to clarify a key aspect of their power: what exactly does science do? Does it merely clarify in some manner or can it predict? Let’s begin with Sir Isaac Newton’s gravitational equation:

What we have here are a variety of forces that we recognize to be unhindered by the human will. G is the gravitational constant (about 6.674 x 10-11); m1 and m2 are simply the masses of two relevant objects (let’s say a planet and an asteroid); r is the distance between the two objects; and F is the ‘resulting’ gravitational force between those two objects. In most circumstances (barring black holes, quantum mechanics, and other more extreme or nuanced phenomena), this equation can be used to predict the movement of given objects if you know the variable inputs.

Much of our confusion with the ‘soft sciences’ hinges on, in my view, this manner in which the hard sciences can sometimes portray themselves as prescriptive despite being more accurately descriptive. The gravitational example I outlined above tends to provide good predictions with celestial bodies because the variables involved in the equation are actually exhaustive; in space, there are few mitigating variables to throw off calculations. This is why we can project celestial movements hundreds or (maybe) even thousands of years into the future, yet we have a difficult time accurately predicting the weather beyond more than a few days. The latter is simply more fraught with prevalent, fluctuating variables. Descriptive power can appear to take on a prescriptive force when there is enough certainty provided by a lack of countervailing forces that could disturb a given hypothesis; for example, though hardly scientific, this is the only reason that I can reasonably think that the sun will rise again tomorrow – not that I have some infallible prescriptive understanding that proves this but that my experience and our comprehension of the sun’s movements makes this a reasonable occurrence to expect.

Nevertheless, though there are many ways in which such descriptive laws present themselves as prescriptive with the hard sciences, I think this is somewhat flimsy even with those forms of research. Despite astrophysics providing seemingly excellent predictions, we can find other fields like immunology or pharmacology that are less convincing of this, even with their practical utility that can affect and predict future occurrences. Indeed, there appears to have been a profound weakening of our trust in these fields after the rather embarrassing confusion and duplicity that surrounded trying to mitigate the harm of COVID-19. This unfortunate circumstance helps us to recognize that the sciences do not fundamentally possess a predictive capacity; they can describe, and – insofar as a given set of variables is reasonably determinable – a hypothetical equation can theorize something that is yet to occur. In some sense, however, this is only as “predictive” as me saying that if I raise a pen in the air and drop it that it will fall downward; this is seemingly certain, though unknown circumstances may undermine this prediction – like someone catching it or a gust of wind blowing it to the side. A conjectured hypothesis can only be certainly true when it is no longer conjectured but actually manifest.

My argument until now has been to say that the notion of any science as prescriptive is simply misguided; sciences are more accurately descriptive and can only be understood as predictive if what they are preemptively describing can be reasonably assumed as controlled and utterly knowable. What, then, about the ‘soft sciences’ makes the descriptive reality of ‘science,’ taken generally, into something problematic? In my view, there are two dominant issues: the first is that even the known variables often remain unstable in definition and therefore are difficult to replicate; the second is that these studies often exist in such a complex social milieu that it is impossible to say that all the variables have been adequately isolated and correlated – more often the known variables have been adequately considered in the analysis, but there looms the question of many other possible factors that went undetected. This means that even the descriptions rendered by the soft sciences are tenuous which consequently means that such theories appearing prescriptive is profoundly unlikely – how could that which struggles to describe ever predict? I will illustrate each of these problems in turn.

I recently heard of study that argues married men experience greater sexual pleasure than unmarried men, who are ostensibly engaging in sex in either one-off or less consistent circumstances. With regard to the issue of indeterminate variables, there is a question as to how one thinks about ‘sexual pleasure.’ What is this a measurement of? We might assume that it is strictly based on self-reporting from the respondents, in which case what exactly they mean by pleasurable is unclear. Is it the act of orgasming in and of itself? Is it the sense of intimacy that a man has with his wife? Is it that he can have an increased sense of pleasure in knowing his wife is also enjoying the experience (which is perhaps less likely if engaged in with a stranger or mere acquaintance)? The measurement itself is unstable and it becomes difficult to understand what exactly is happening given its vagaries; if a married man were to say that his sexual pleasure is low, he has no understanding of what another man is experiencing and how this can inform his own experiences.

Closely allied with this issue is the problem of variables being difficult to isolate or pin down. For example, this study I have invoked seems to suggest the following, at least in its title: marriage is the key variable that increases the sexual satisfaction of men. The issue, however, is that marriage is not necessarily a clear explanatory marker (as the study itself recognizes). Marriage, in some sense, stands in for a number of other variables that can easily be teased apart: cohabitation, long-term commitment, openness to children, mutual finances, etc. All these different aspects may comprise some marriages, but there could be other marriages that lack some of these aspects and consequently fail to achieve that same level of satisfaction. We then have a question: is the causal factor marriage unqualified or a specific understanding of marriage? What if marriage as an institution radically transforms? Would these findings not then become immediately obsolete (or at least need to be translated into some other terminology)?

In my view, the phenomena that social sciences tend to deal in are deeply complex webs that are made up of our own self-understandings – and these are frequently opaque even to ourselves. It seems unlikely that the findings of these studies provide much of substance beyond some superficial glosses of what particular people self-reported in their specific circumstances. No doubt, to call them prescriptive is foppery; to call them descriptive is somewhat equivocal. To know, as a man, that ‘married men’ experience greater sexual pleasure does not imply that simply running to the courthouse and signing a marital contract with a mutually intrigued female friend will result in better sex. The headline simply misses the reality. Nevertheless, as contingent and ephemeral as such a finding may be, I maintain a kind of naive optimism that such studies can be a place where more profound probing and enquiry can begin; one might question what the deeper realities of such a finding entail which may spur on a more profound set of questions and reflection. Moreover, there may be some value in simply capturing a moment of what various people understood about themselves and having this well coded into a dataset.

This, in my view, is ultimately a better understanding of what the ‘soft sciences’ provide: a variety of statistically coded, historical snapshots. Such studies capture for us a brief moment of what a sample of a given collective understood about themselves, and this can have intriguing historical and developmental possibilities. What would be evident, however, is that such an enquiry would inherently be ever-backward-looking, and to believe that anything prescriptive could ever be derived from such exercises is simply to misunderstand the nature of the initial form of thinking that was performed. No science is really predictive, but those sciences wherein the variables are unstable and perhaps superficial (a near necessity with evermore complex phenomena such as ourselves) can never hope to attain even descriptions that are conjecturally forward-looking. To understand ourselves, we do not need to know some aggregate of what a given sample of people thought about themselves; to understand ourselves, we must question the very thoughts in our heads – a task properly suited to philosophy, theology, and theory, and only supplemented by other forms of enquiry.

One thought on “Social Sciences: Misapprehensions and Misapplications”