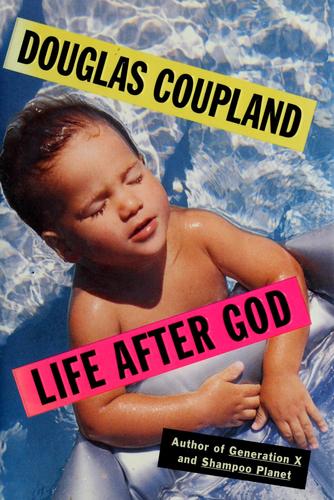

Writing a book review for a rather obscure little book that was published thirty years ago may seem an odd pursuit, but such might be justified when circumstances give rise to fresh relevance in a given work. In the case of Douglas Coupland’s Life After God, published in 1994, I think this is a book that, though hardly a classic, provides a profound snapshot of the spiritual moment we are enduring – granted, given that this text has been on shelves for three decades now, it has been a rather long moment. I will admit to you that this is a favourite book of mine; I have probably read it eight or nine times over the last five or so years since I found a copy in a little used book store that I once frequented. I say this while knowing that the book is rather unimpressive in terms of its literary quality. Life After God is in many ways a book that makes little sense outside of the context of late twentieth and early twenty-first century North America, though I think that is precisely why it is such an impressive snapshot – it captures something so particular with great lucidity. I would go so far as to argue that the secularization and lacking contact with the transcendent has only increased in our day, and this provides the book with a renewed sense of insight.

The author, Coupland, is a man about whom I know little. I have heard him referred to as a ‘futurist,’ though I have no idea what that means. He has lived much of his life in Western Canada, specifically British Columbia, though I believe chunks of his life have been spent elsewhere, like in Germany and Japan. He tends to be called an author, designer, and sculptor – though I doubt this is all he does. I am entirely ignorant of what he has ‘designed’; his sculptures that I have come across strike me as contemporary nonsense that could only gain prominence in a postmodern age; and his fiction tends to be…fine. I have read few of his books by now: Girlfriend in a Coma, Bit Rot, Worst. Person. Ever., All Families are Psychotic, JPod, and Binge – though I must admit that they have left almost no real impression on me; I cannot remember anything about JPod, Binge was contemporary mush, and the rest were seemingly passable but inconsequential fare (though I will cut Girlfriend in a Coma some slack – despite not being fantastically executed, it plays with some worthwhile ideas and plotlines). For me, then, I find it all the more intriguing that Coupland would be the author of a fictional text that stands out to me as so pivotal.

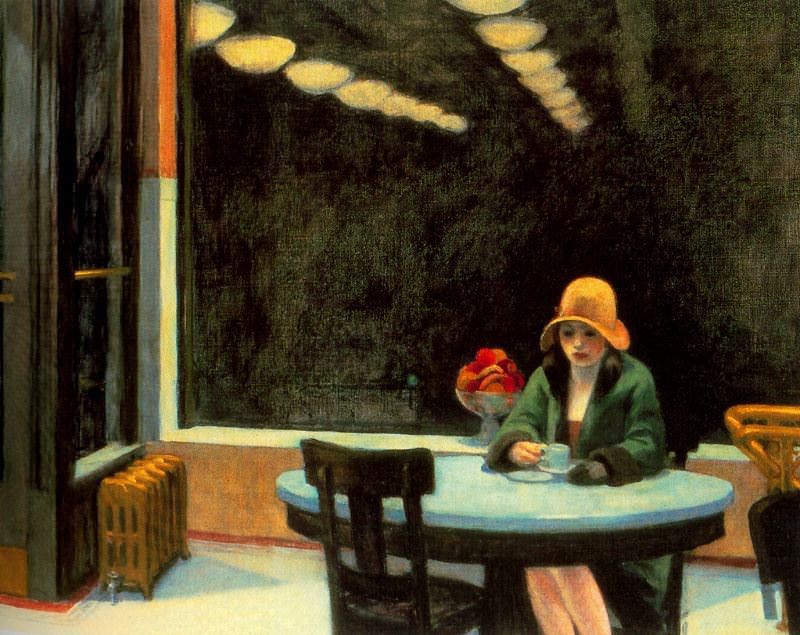

Life After God is not precisely a novel, as it is not a singular narrative. It is – most precisely – a small collection of short stories, but the grounding themes of the stories are so deeply interwoven across the various narratives that one gets the impression that it is depicting the experience of a single soul or spirit across several distinct characters. It is filled with cute, little black and white drawings, on every other page or so, that modestly complement the tales in various ways. It is quite brief – I think my most recent reading of it, in which I deliberately took my time, was under three hours. All the stories focus on characters somewhere near the Western Coast of North America, either in the United States or Canada, going about their lives. They endure varying degrees of depravity (though the general tendency is to be dramatic by comparison to real life, which is a common theme in all Coupland’s writing), and ultimately they are all dealing with – at some level, either explicitly or implicitly – the problem of ultimate meaning. Whether in dire or suitable circumstances, pleasure or pain, all the characters tend to be wrestling with a seeming lack of purpose – hence the title of the work. I continue below, but I first want to provide a number of excellent snippets from the book – I list them in the order they appear, though they are not necessarily equidistant from one another in the text.

Time ticks by; we grow older. Before we know it, too much time has passed and we’ve missed the chance to have had other people hurt us. To a younger me, this sounded like luck; to an older me, this sounds like a quiet tragedy.

But she says there’s a difference. She tells me that at least when she was younger she felt lost in her own special way. Now she just feels lost like everyone else.

He said our curse as humans is that we are trapped in time – our curse is that we are forced to interpret life as a sequence of events – a story – and that when we can’t figure out what our particular story is we feel lost somehow.

This was one of those conversations where you looked at the scenery, not each other. I said, “Yeah, I do worry if I’m past love – or if that capacity was even there in the first place.”

I thought of how an embryo doesn’t know where on Earth or when in history it is going to be born. It simply pops out of the womb and joins its world. The landscape I saw before me is the world that I had joined, the world that made me who I am.

From just these brief excerpts, you will glean that there are some common themes that run throughout the book: love, temporality, identity, nihilism, and introspection, just to list a few. There is a perpetual understanding that time is passing and there is plenty of pain; yet everything seems fine and, in many ways, probably is fine. There is no starvation, no real war, few debilitating illnesses (and those that come up can largely be abated), and you can basically get whatever you want. The major frailties and concerns that have plagued the human condition are, within the context of late twentieth century North America when and where these stories take place, largely unknown in any immediate sense. Such a world might appear almost heavenly, as if mankind had made it back to that perfect garden; sure, there are annoying jobs that one plugs away at, maybe the odd drug or drinking problem, and a general sense of solipsistic alienation, but we have been told this is the best time to be alive – so this must be the way. If things do not feel alright, there is probably some kind of pill your doctor can give you to help with that.

I think, however, that Coupland points to a rather profound insight about the human predicament of contemporary, North American society, though the text does so negatively as none of the characters seem to expressly acknowledge this fact: human life must end. The human circumstance is unique for precisely this reason: we are Sein zum Tode, to use Martin Heidegger’s phrase – being towards death, and we ultimately know this fact. The theme of temporality is deeply interlinked with this problem throughout Life After God. Without a sense of death or finitude, there is no sense of an immanent conclusion; without the notion that things must be wrapped up, there is no sense of how they ought to be moving. I have often thought it funny how the Greek gods are frequently portrayed as these super-beings committing one immoral deed after another – but, upon reflection, we might ask what else they ought to be doing if they simply live forever. For an immortal but limited being such as those ancient deities, there is no sense of consequence; without consequence, there can be no salience to anything save the pleasure found in each passing moment. In many ways, the world we live in – and which Coupland conveys so simply – is one in which human beings have come as close as they ever have to such immortality, though now the worshipped is simply the worshipper.

This, in my view, is the great insight that Coupland is able to intimate with these fictional stories: what is ultimately novel about our time is not so much that we have lost a sense of the divine but that we have worked to effectively eject any recognition of death from our lives. (I have noticed more and more that people no longer have funerals – they have “celebrations of life,” which quite clearly points to a rejection of the present reality of death, nothingness.) Nevertheless, this is but an appearance – our awareness of an inevitable nothingness, resting below all we do, can never be entirely shaken. This reality, then, even infects our beliefs about the goods of our time, which may be genuinely good; yet, to be ignoring something so inevitable and fundamental as the impermanence of our existential condition winds up sullying the whole effort to ameliorate proximate sufferings – even if we have done this with such efficacy. I came across an argument for why religion matters, and there are three main aspects of religion: 1) reconciliation with tragedy, 2) reconciliation with evil and sin, and 3) reconciliation with the inevitability of nothingness. Ultimately, however, it was posited that the last of the three was the most fundamental. In some sense, there is something to be done about the first two issues of tragedy and evil within this life; one can explain away these forms of suffering and impose technological changes that help to take away their sting – and, ostensibly, our present culture has gone further than any other in achieving this end. Technology cannot, however, take away the inevitability of nothingness; despite what a ‘transhumanist’ philosophy might try to persuade us of, we know that existence itself must come to a close – the heat death of the universe, if nothing more proximate, is inescapable. In light of this, what does it matter that we have staved off immediate, temporary suffering?

Lacking any confrontation with, let alone answers to, the fundamental reality of the nothingness that rests beyond all we know, there can be no sense of peace – even with all we have achieved. Every character in Coupland’s Life After God knows this, but they have simultaneously been formed by a world that says that there are no such answers or considerations to be had. In such a world, we should expect that people seek out love, acceptance, and recognition wherever they can find it, for it is only in these endeavours that anything is given a momentary permanence (even if nonetheless temporary like all else); given our ever strengthening technological capacities, we use every tool at our disposal to get beyond the evanescent status of all our affairs. In many ways, Life After God both reflects the problem of our time and the perhaps more dangerous problem of us trying to invent solutions – something we are so apt to do when we have been able to control the problems of suffering so effectively, whether from tragedy or evil. The issue with these concocted solutions, such as faux-spiritualities or otherwise, is that they seek to gloss over the inevitability of nothingness; they seek to provide an immediate answer to an eternal conundrum. We will, like many characters developed by Coupland, begin to seek out palm readers, drugs, nature, or sexual frivolity to have a sense of encounter with a world beyond ourselves in which we can find meaning, anything just to feel something – but this too shall be eaten away by the nothingness, and we must inevitably seek something more.

Now – here is my secret:

I tell it to you with an openness of heart

that I doubt I shall ever achieve again, so I

pray that you are in a quiet room as you hear

these words. My secret is that I need God –

that I am sick and can no longer make it

alone. I need God to help me give, because

I no longer seem to be capable of giving; to

help me be kind, as I no longer seem capable

of kindness; to help me love, as I seem to be

beyond being able to love.

Ere the wholesome flesh decay,

And the willing nerve be numb,

And the lips lack breath to say,

“No, my lad, I cannot come.”

-A. E. Housman

I had thought of reading this years ago—and never got to it. Now I understand why it was so popular among my peers!

May I please borrow a copy? 😏

Ennui, Weltschmerz, Sehnsucht…

LikeLike