My wife and I were recently sat in our living room enjoying some tea, and our conversation turned to her asking me a few questions about my return to Faith. She, having grown up in the Church, has had quite different experiences than I, and our conversation occasionally turns to these matters. It is always edifying to hear someone else’s innermost struggles on these topics; it tends to make one desire to go more deeply into oneself. This particular conversation jogged my memory about a very early intuition that had struck me when I was still, at least in a self-identifying sense, an atheist. While reading a number of authors such as St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, and Dante Alighieri during my undergraduate degree, an idea struck me that I could not shake and which, truthfully, I have never shaken: the world is made with and of love. I had an inclination that I meant this metaphysically, but that was about all I could make of it. Nevertheless, I began to believe that claim, and I soon found myself spiritually searching and eventually landing back in the Church.

I recognize that this claim is vague and perhaps too whimsical for most – it almost has a flavour of some New Age philosophies that have emerged within recent history. I only tell you this because it is the honest truth; now, the fact that this led me back to the Catholic Church, I will leave you to think about. I am unconvinced this is a coincidence, but perhaps it is. Nevertheless, when one is engaged at the level of the spiritual and metaphysical, one tends to encounter a great many more problems to think about for oneself. In my case as a Canadian, there was one that became particularly salient: euthanasia – or, as it is so horribly called in my home country, ‘Medical Assistance in Dying’ or ‘MAiD’ for short. Granted, even the literal meaning of ‘euthanasia’ hardly describes this brutal reality at all.

The legislation in Canada was first tabled eight years ago in 2016 after a Supreme Court of Canada Case, Carter v. Canada, deemed that the criminalization of euthanasia is contrary to our Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the supreme document of the Canadian Constitution since 1982. In my view, this decision vindicates the idea that the Charter merely instantiates a kind of neo-Lockean, atomistic individualism (meaning that the individual is considered entirely self-contained and, if followed to its logical end, responsible to nothing he or she does not choose to be) into our legal system, and this is the logical fruit of such a weak understanding of the human person. Regardless, my intent herein is not to comment so much on the Canadian case, therefore I will simply provide a link that sets out the basic terms of how the Canadian government has dealt with this problem. My concern here is rather with the reality of euthanasia and what it implies.

Now, I recognize that, in just three paragraphs, I have gone from talking about the world being metaphysically structured by love to discussing euthanasia. This is not merely my tendency to free-associate overtaking my writing, but I do this with a specific intent: euthanasia is predicated on a view of life that does not put love at the center. My intent here is merely to explicate that claim. I will not, however, be arguing herein that love being at the center of life is the best way to live or some kind of normative ground for morality; I think that many people will find that claim self-evident (as I do), but it would also require many more words than I am already using to make my more limited suggestion herein. Thus, I am narrowing the task of this essay to merely outlining the oppositional relationship between love and the practice of euthanasia. For my present purpose, I follow the Thomist tradition of describing love as willing the good of the other for the sake of the other, a self-giving only with intent to enrich the other for his, her, or its own sake. In my view, euthanasia always opposes love so understood.

A typical justification for euthanasia takes one of three forms: 1) human beings, as free agents, should have the capacity to decide when they die; 2) people should not be forced to suffer if they do not want to; and 3) insofar as one’s condition makes him a burden to those around him, he should be able to elect for euthanasia in an effort to unburden his caretakers. There are some other arguments that might be leveled, but I believe they tend to be variations of merely these three. Arguments about quality of life and preventing suicide by other means are reducible to the first argument, and arguments about the limits of palliative care are reducible to the second (and maybe the first, depending on the formulation). The third I do take to be somewhat independent from the other two. Each must be taken in turn, as the they have herein been listed in order of least to most persuasive, at least as far as I understand them.

The claim of freedom or liberty for the legality of euthanasia is rather misleading. Typically, claims about ‘freedom’ – in the sense of mere choice – ought to be reigned in by the ways in which freedom can be self-destructive, and we must always recognize that freedom for its own sake is a meaningless principle. Perhaps this shows my cards, but I am hardly of the modern persuasion on this front: I believe that true freedom is the freedom to do the good (in my view, this means to act in love), and mere choice for its own sake is of no value. This is the basic principle underlying virtually any respectable legal system – what is prohibited are those actions that evidently collapse one’s capacity for free choice toward the good. The legal order need make no explicit claim about what the good is in an absolute sense, but we have collective intimations of what it is not that we can codify.

Nevertheless, even if one were to say that they disagree with me on this front and suggest that freedom in the sense of mere choice is the absolute good, we have already arrived at my conclusion: this view of things does not put love at the center of life. Logically, this view must argue that any number of choices are fine because they are based on freedom: adultery, abuse, abandonment, etc. – there are no grounds for saying that these are wrong, since they put freedom in the center. Evidently, I think no one really believes this, but many people will dip into this kind of language when they want to obfuscate the moral question of a particular issue. What I hope is evident from this is that we must begin to question what ‘value’ or ‘good’ (or lack thereof) is being aimed at with a specific action, and this claim would then need to be adjudicated on moral grounds – freedom is insufficient.

This leads into the second argument about why euthanasia should be considered legitimate: people should be able to end their suffering because suffering is an evil. If we wish to frame this more persuasively, we might say that people should be allowed to end their purposeless suffering which serves no good end. This distinction is nontrivial, and it partly explains the problem with the claim that death is a legitimate solution to our suffering. In many cases, suffering can be endured for the sake of a greater purpose; we might imagine someone enduring a surgery and prolonged recovery or even a mother giving birth to her baby. In each case, there is evident suffering, but there is also a clear good to be derived from that suffering. These are not the cases being discussed here, as the pursuit of death in such instances would (I hope) appear self-evidently incoherent. What is perhaps less affronting is the idea of someone wanting to end his suffering where he has no clear positive moment in sight; we might imagine an elderly person suffering from a terminal illness.

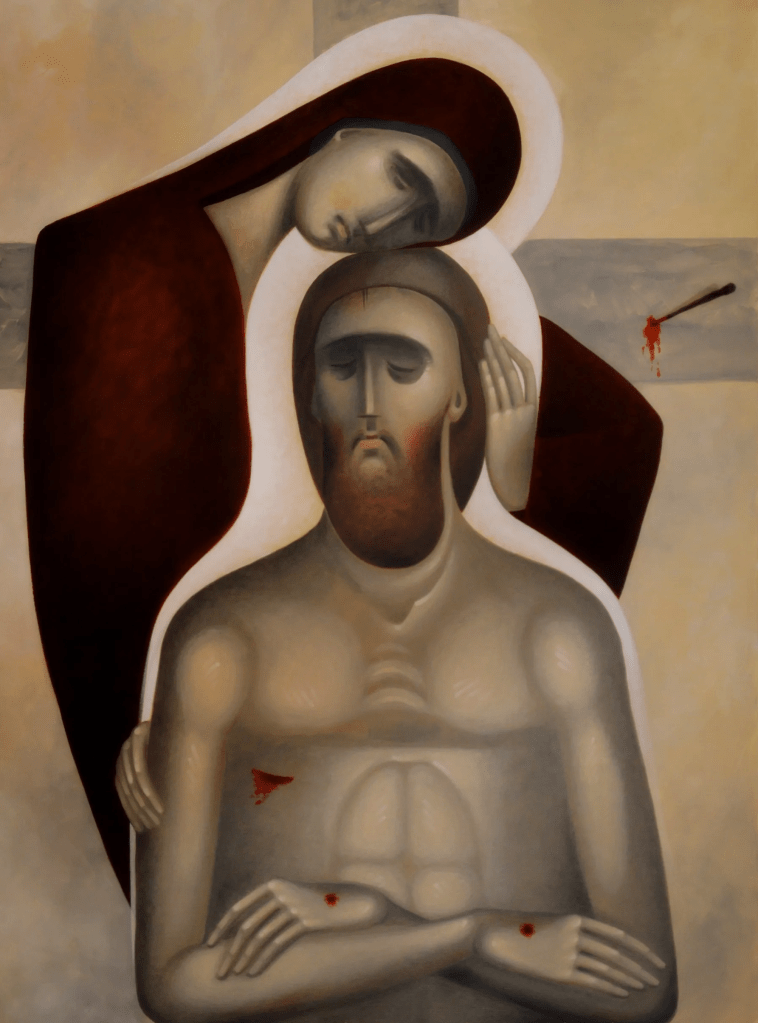

Even in this circumstance, I believe that to choose death is to be unloving. Firstly, one does not know that one’s suffering will be for naught until death comes of its own accord; if this be so, let it be so, but the active movement towards death confuses this natural limit of our being. What if a man could have produced just another laugh or provided another word of wisdom even amidst his suffering? To hold onto this life that has been given for as long as possible allows for the chance to care for the other, to choose love; to choose death, even to be rid of seemingly meaningless suffering, is to suggest that the acceptance of death is better than the potential remaining in oneself to love others and provide something of value, even if this is nothing more substantial than a smile or an image to contemplate.

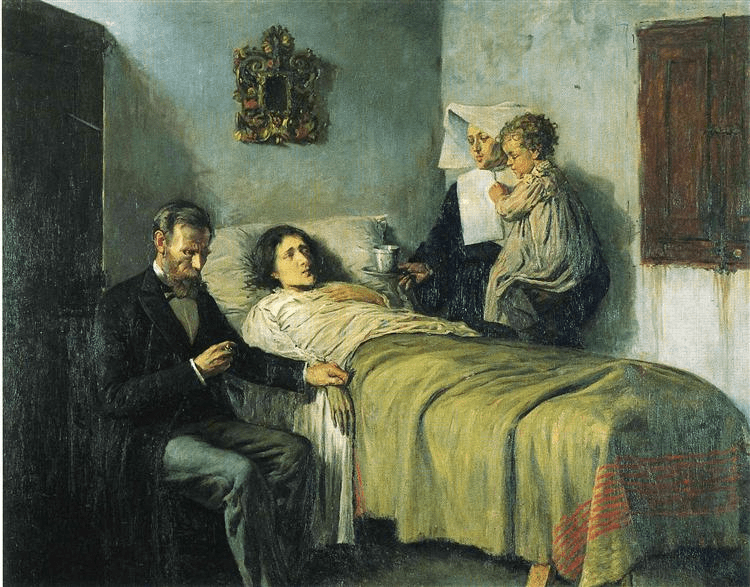

Finally, we come to that justification for euthanasia that appears the most sympathetic – that one’s death will provide others with a reprieve from the burden of caring for oneself. An elderly man might fear that his ill condition will place an undue burden on his aged wife and therefore opt to pursue death, as he believes his absence will be better for his spouse than his diminishing existence. Given what I said above, we must herein preclude that he is saying this out of a sense of his freedom or to avoid suffering. On the grounds of this third justification, he is merely concerned that he will be a hardship upon his wife, and this is his only motivation for desiring death. (We can imagine those cinematographic deprivations of war: “Just go on without me!“) I must admit my sympathy with this view; but I ultimately think that it is nonetheless faulty.

In such a case, there is nothing obligating the other (such as one’s wife) to care for us. I have, perhaps, a too radical view of human freedom, but I believe that the spouse of a sick man could simply neglect him and let him die. If the ill husband is truly concerned only about the wellbeing of his wife, then this should not bother him; if she chooses not to care for him then she will not be burdened by him, and his decision to pursue euthanasia would therefore need to fall back onto one of the two prior reasons with which I have dealt above. Moreover, if he remains alive, even in his sickly state, he provides the opportunity to his wife to love him with her hospitality and nurturing – our own weakness and illness provides a clear space within which the goodness of others around us can emerge in their loving care. To take one’s own life is to deny the possibility of love, even if done out of a concern that those one loves may be burdened by one’s ailments.

This is a brief statement, but I hope that it has at least presented to you a tension between the ideal of love and the practice of euthanasia. I realize that not all can be forever perfect; we human beings are fallen and frequently make compromises in a number of important matters. It strikes me, however, that the killing of our fellow men is an easily avoidable and condemnable action that several of our societies and their respective governments have bizarrely accepted without much thought. Perhaps we are too infatuated with an overly individual view of human fulfilment as the gratification of pleasures until this is no longer possible, which might suggest the need for termination when this endeavour is seriously frustrated. But I hope this also strikes you as evidently reductive and incomplete for how we must conceive of ourselves and the purpose of our lives – and perhaps we might reconsider the implications of peoples and governments who sanction such actions, especially when we are among them.