Our age is, by and large, one that we might describe as individualistic. What precisely is meant by individualism is not always clear, though I believe there are some common tendencies in the way that this word is used today. This notion was perhaps best captured by J. S. Mill in his seminal On Liberty, though traces of it can be found throughout the liberal tradition from its supposed beginnings (though incompleteness) in thinkers such as John Locke to its continued extrapolation among figures such as Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek; moreover, there are similar (though muddled) statements found in libertarian thought such as that of Robert Nozick and Ayn Rand. This suggests that the individualism of our time is not new, but we should not mistake this claim for a defense of its desirability; my view is that this individualism is problematic, though I believe reactionary forces against it have become a problem of their own. This has radically jeopardized our understanding of the individual as a political entity – and I want to reconsider this.

My thought here is not directly influenced by any one figure, though I surely have many sources to whom I owe debts. Unfortunately, it is a wide range that might seem incoherent upon first glance, though I suppose this is made coherent by understanding that their invocation here says more about me than them: Plato, Aristotle, St. Augustine, Thomas Hobbes, Michel de Montaigne, David Hume, Robin George Collingwood, Michael Oakeshott, and Alasdair MacIntyre (and many others) all rest in the background of my thoughts on these matters – though none of them is quite exhaustive of what I shall say here, and I will say much that also runs afoul of (as far as I can tell) various things that each of them have written. I, moreover, note this not to give credence to my statements but in order that, if you are so inclined, you might try to piece together my idiosyncratic considerations for yourself.

In order to explain my concern, I must first begin by describing what I take to be problematic about our colloquial understanding of individualism that, I believe, is found with those figures (among many others) whom I mentioned at the outset of this essay. From there, however, I will explain my objection: these theorists provide rather incomplete anthropologies that, I think, lead to destructive self-understandings for us human beings. I finish by attempting a brief alternative to such individualistic theories: I advocate for an understanding of individuality as the embrace of embedded self-understandings that can ground community and collectivities. This is a view of the human person that I believe we can both find more desirable and that we will recognize is not a merely modern phenomenon – though it may have emerged, but for a moment, more poignantly in the early centuries of this era.

As far as I can tell, these figures who espouse an individualistic ethic – such as Locke, Milton, Hayek, Nozick, Rand, and others – all assume that the human person is inherently ‘rational’ and ‘ready’ to be an individual in some abstract and unclear sense. This is the central claim to which I am objecting. I do not think that many people can properly be considered as individuals – a criticism which easily applies to myself no less than anyone else – for they do not have the strength of will, sense of self, and virtuous training necessary to be an individual. Even more critically, I do not believe that people ’emerge-from-the-womb’ as ‘individuals’; individuality as I am herein expressing it is not an innate quality of human beings. No doubt, I believe that each person has an intimation of will and can make his or her own decisions – a reality which seems to be a universal human trait, but that is not quite the notion that I believe the aforementioned individualists expound. I, rather, would contend that true individuality in human beings is something that is learned and therefore has an historic quality; one can trace this sort of personality’s development, its waxing and waning, and consider its concrete manifestations throughout time.

Following the suggestion of many others, I would contend that early modern Europe is characterized by a shift toward understanding society and self on the basis of individuality. What we mean by this is that individuals begin to be understood as explanatory foundations of identity in their own right; people are no longer defined solely by their associations, given to this church and that guild, but now are understood as having an independent solidity. Personhood becomes primary over affiliation: this is the modern European creed. This claim, perhaps, comes to a high (even screeching?) pitch in the aforementioned On Liberty of J. S. Mill, a text that decries the ways in which individuals and their personal experimentation are subject to communal ties and the prejudices of collective habit. At one level, we might read Mill as making a legitimate point: the imposition of unthinking habit that quashes creativity or innovation is certainly undesirable; to allow people to think things through for themselves should be welcomed so as to ensure a fulsome manner of living. Mill, however, in my view, bends the branch too far in the opposing direction. He comes near arguing that habit and custom are themselves evils, for they imply a kind of blind reception and passivity. I think this is an obvious error, for one can surely encounter a custom and think it through in such a manner that one finds it both valuable and worth preserving – habit and custom are not necessarily dumb.

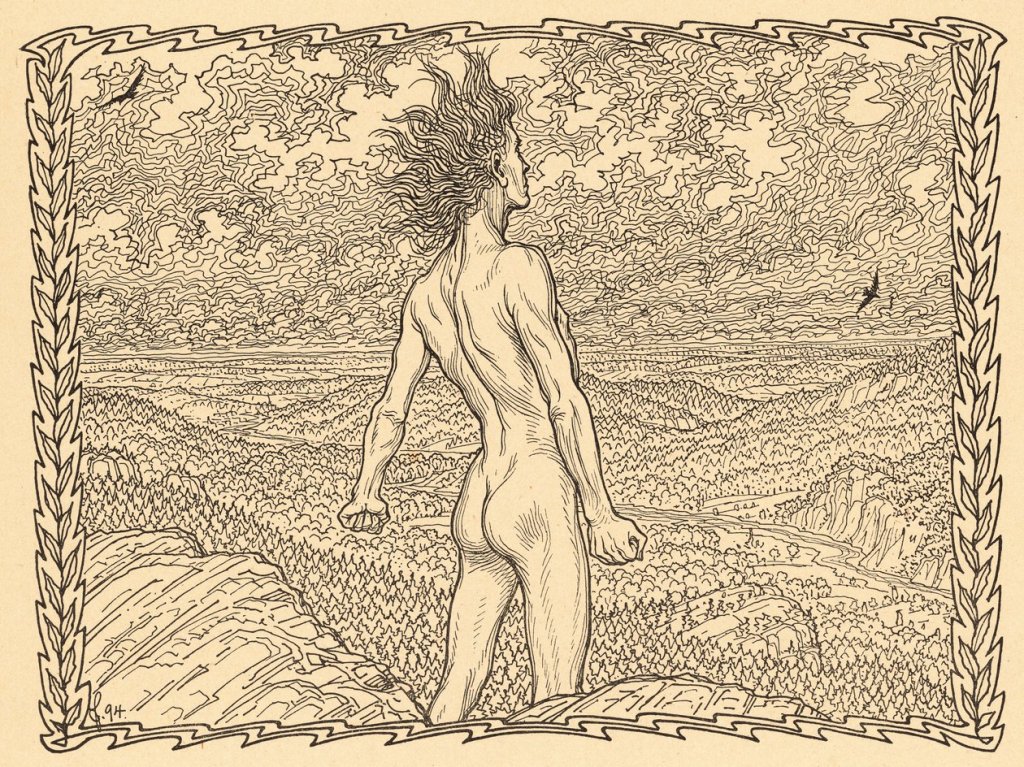

This is the central flaw of the overly individualistic impulse. It conflates the unique with the good, the habitual with the bad, and suggests that the individual must be radically independent in some manner that is not self-evidently justified. When one reads Mill, there is a sense in which all familial and communal affiliations mean nothing. I believe this to be a foolish misunderstanding. There is nothing that precludes a man from honourably enduring in his place – whether as a son, brother, father, or friend – in a manner wherein he recognizes this reality to be something chosen and willed for himself; I mean ‘chosen and willed for himself’ not in that these qualifications entirely justify a given action but that they strengthen his attachment to them. In recognizing his own person and meaning in these roles – not merely because they are his affiliations but because he has freely chosen them in addition to their imposition upon him – he comes to bear them with a greater fervor and justification. To be an individual is not to be ‘independent’ of one’s contingencies in some abstracting sense but to have independently understood these contingencies as conditions chosen and bore willingly (as opposed to doing so out of a misconceived notion of necessity).

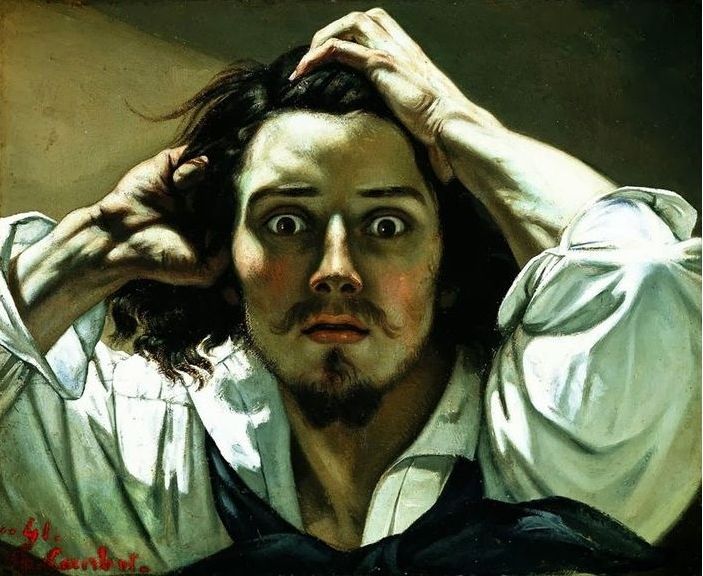

When we conceive of the individual in this manner, I believe that we can begin to see intimations of individuals from long before the modern era – and some of these examples may even suggest something that the modern era (or perhaps now the post-modern era) has already lost. The individuals I am herein describing are not considered to be individuals because they understand themselves as unshackled from their communal ties and rejecting all that is ‘given’ within their traditional and social circumstances. Instead, what makes an individual is someone with a profound recognition of his station within the contingencies of life who chooses to bear them precisely because he recognizes their importance and goodness. This requires a reflectiveness and willingness that must be procured with great care; it requires an encounter with transcendent considerations and confrontation with questions of death, the void, infinitude, and existence as such. This is not something with which we human beings are born but something that must be learned – indeed, this was once a primary objective of ‘liberal arts’ education as I understand it. An individual is not designated as such because he is isolated or alone but because he becomes a grounding point upon which the community can rely; he is called an individual because he has risen from being a mere affiliate within various associations to presenting himself as the very ground upon which one ought to reflect and perhaps even emulate.

When we reconsider the meaning of individuality in this manner and avoid the atomistic stupidities of the most recent centuries, I believe that we find something worth pursuing and defending. This is a personality that I have detected in the authors of a great many texts. Those who come to mind are figures from whom we have the deepest writings or of whom we have great testimonies; it is these prominent historical characters who have most easily endured the destructive flow of time that, like a gushing stream, gradually polishes away all but that which is most durable. Those who come to mind are titans no less than Anicius Boethius or Dante Alighieri, though I think the greatest philosophic figure that memory is compelled to recognize is the indominable Socrates. Moreover, I think that great Athenian teacher is a perfect example here for he does not claim the simplistic notions of Mill in that the individual must be freed of the prejudices and ignorance of his time; Socrates did precisely the opposite and used those shortcomings of his age as the foundation for his reflections, and – when the collective suggested that he must be destroyed for his individual character that so challenged and pushed them all – he consented to his own demise at the hands of his fellow citizens from whom he had been given this disposition to question and probe. The individual is not set apart from his contingent moment; he is merely an anchor in maintaining its strength and profundity.

Ultimately, I must admit that I see the notion of individuality fully expressed in that most important figure of all history: Jesus Christ. It is, perhaps, no surprise then that this modern individualism as I noted above should arise on the European continent where Christ’s teachings became so widely recognized and held. In some sense, the notion of individuality as I have expressed it here – a view that avoids mere individualism – is brought to perfection in that simple phrase uttered to anyone who wishes to find the fullness of life: ‘Take up your cross.’ This phrase suggests that we are not the ultimate arbiters of our circumstances and there will be travails; nevertheless we may, if we self-consciously adopt our contingencies knowingly and with a near-divine willingness to endure, find that transcendent purpose is most clearly found in fathoming the depths of one’s own heart more than seeking such meaning in anything ‘in the world.’ As like as not, such pursuits may even require a bravery that allows us to enter willingly into death – but there is a hope of Resurrection and a greater Life to come.