The nature of beauty and its reality as something ‘objective’ or ‘real’ has, as far as I can tell, been utterly corroded in recent centuries. As someone who loves poetry, I have found that many people resist my preference for formalized poetry and my tendency toward lofty themes. When I argue that poetry should help instill a sense of delight and wonder in the writer and reader, I am frequently accused of being rigid and exclusionary in my definition. Of course, the alternative that is offered by my critics tends to be no definition at all – poetry is whatever you want it to be! This, no doubt, annoys me beyond belief, but it seems that I am rather outnumbered in trying to win this debate. Nevertheless, I think my view can be developed somewhat further so as to try and persuade us away from such relativism.

To this end, I first must make a distinction that many may well find pedantic; I intend to distinguish between poems and the poetic. No doubt, poems participate in the poetic, but I take the latter to have a much more expansive reality than people tend to assume. In considering the poetic, however, I think that what is occurring more specifically in a poem might be reconsidered with regard to the importance and beauty of form that is not afforded by the ‘anything goes’ understanding of poetry; though, at the same time, my views elucidated here will also provide some room for those who wish to retain their looser definitions of what is meant by poetry.

In my view, poetry is best understood not as an ‘object,’ not as a something in the world, but rather as a manner of experiencing. I believe that we human beings engage with the world in a number of ways that have their respective places and importance. Most commonly, we engage with the world as a series of desires and aversions, a world understood as good and bad, which is most developed in religious thought; alternatively, there are ways of trying to understand the world, which emerge in such forms as philosophy, science, or history (among others). I believe that poetry is an alternative to these ways of looking at the world; poetry is not about moralizing or explaining – it is about delighting in the contemplation of a moment.

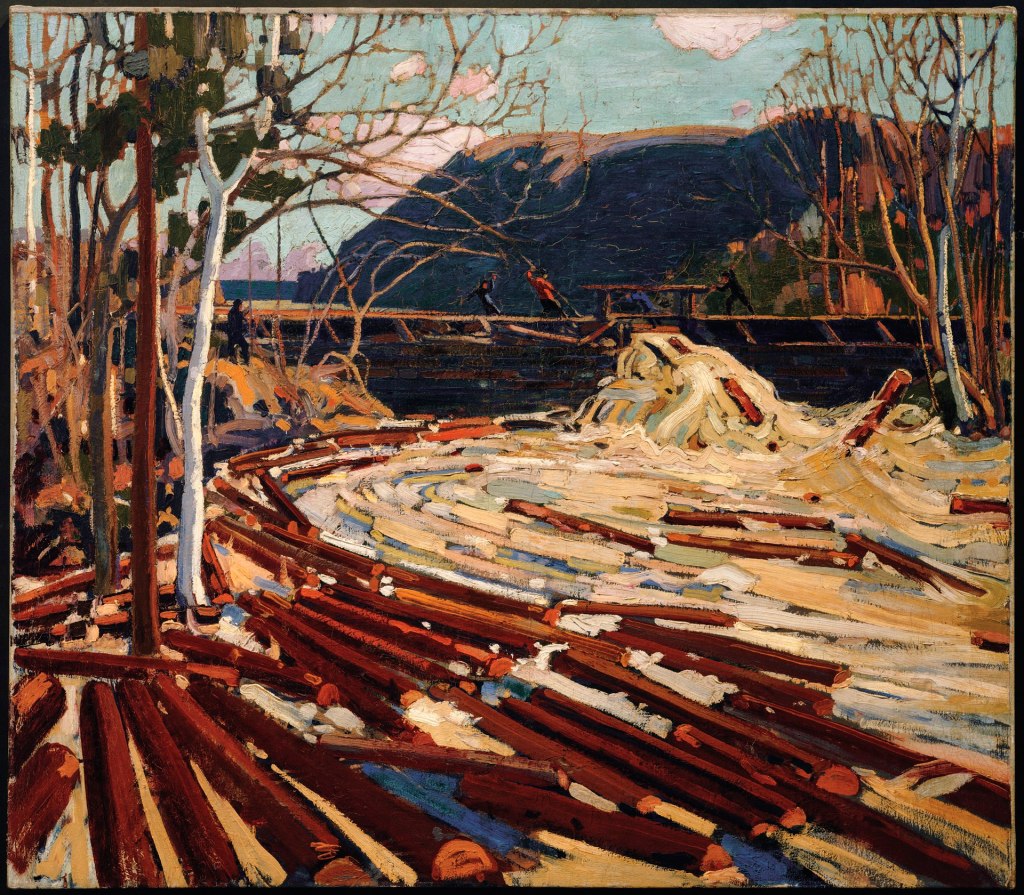

If I am allowed to rely on common sensibility for a moment, I believe that everyone has experienced times in which (especially in nature) we are struck by a scene in a way that requires no explanation – the very moment presents itself to us as its own justification. For myself, I most frequently find this in the sight of late afternoon’s blue sky populated by prominent clouds that sit perfectly as if painted by God Himself; for others, they might find this in the sight of a willow tree or the rushing of a waterfall – though it need not be merely in nature, as one might find such delight in architecture or a human face. Though this is hardly an argument, I believe to have such an image before the mind’s eye helps in considering what is happening during such experiences.

I believe that the ancient Greek distinction between praxis and poiesis may help us in considering what I am herein describing as poetic experience. For the Greeks, praxis is a term connoting actions or activity as such. One’s daily routine might be considered relevant here. Poiesis, however, is a more particular form of activity in which something that previously did not exist is revealed by an agent; thus, one might associate poiesis with inventiveness or ingenuity. Something like the creation of a harp to produce a new musical sound or the invention of the steam engine to produce more energy and faster movement could be considered ‘revealings’ to which poiesis points.

My understanding of poetry is analogous to this notion, but I intend it in a slightly modified manner from the description of poiesis provided above. As opposed to revealing in a broad sense, I understand poetry to reveal the character of something on its own grounds in a manner that is perhaps missed when engaged in practical, philosophical, or scientific ways. Poetical experience is an encounter with a given object in a manner that is done strictly for contemplating the thing on its own grounds in the hopes that the object may reveal something to you in itself so long as you observe it gently enough; this stands in direct opposition to other ways of experiencing the world in which we try to use an object or explain it in some manner. This need not be a physical object, though it certainly can be; one may poetically engage with justice or love just as much as a rose or a mountain. What is central to the poetical engagement is merely that one wishes to allow the appearing of the object to stand for itself and to embrace that moment for its own sake.

There are two brief notes to be made about this view of poetry. The first is that these moments of poetical experience are much more common than any concrete art or craft that attempts to share this poetical experience with another person through a given medium; indeed, I believe that people who have no artistic ability of their own can frequently experience the poetic – we all, regardless of our artistic talents, have moments in which we are struck my some idea or image. It may be true that those who are overly concerned with practical affairs or explaining the world in some manner may be less inclined to such poetic delight, but I would contend that it breaks through almost everyone’s daily monotony at some point or another. The second note, which is implicit in the first, is that poetry as I have explained it here as a manner of experiencing is the primary ‘source’ from which arises all forms of art, whether that be poems in the restricted sense or in painting, sculpting, composing, or acting. Of course, we tend not to speak in this manner colloquially, but I believe this understanding of the poetic as the general form of experience from which all arts emerge is enlightening when reflecting upon this experience in the manner I am here.

With this cursory definition of poetry established, I now wish to turn to poems themselves in the restricted sense to explain why I believe formalism is a deeper engagement with poetic experience than the loose definition of poems being whatever you want to define them as. I am sure people that employ this more relativistic definition have a similar idea to my own about the general notion of the poetic; they do not wish to restrict what can become the object of contemplation, so they encourage people to find it wherever they can. In some sense, I am both sympathetic to this notion and encouraging of this pursuit. Where I differ from this idea is that I believe formalism is itself a way of contemplating the very language being used in addition to the object in question. Thus, a poem about a lily becomes not only a way of trying to convey the experience of observing the lily but a way of contemplating the very language one is using and allowing its intricacies to move the manner in which the lily’s beauty is conveyed. Let me provide two brief examples to indicate my meaning:

The lily rests with quiet patience as if waiting for me

to see it and remark upon its graceful poise,

its delicate form too bold to demand a compliment.

or

In quiet patience is the lily stilled,

As if ready for a perceptive eye

To promptly stop despite just passing by

and mutely praise – so bloom’s design fulfilled.

I think that both of these examples have their respective virtues, and of course the meaning they are conveying is not quite the same. Nevertheless, I believe that the second allows for both the writer and the reader to engage in contemplation not only of a lily but of the very language that is being used to represent that poetical experience of observing the lily in the first place. In a poet attempting to be controlled by form, whether that be rhyme or meter most commonly, he is forced to consider not only the thing he is attempting to convey but also the very method of his conveyance. (As an aside, writing the second example took me much longer, perhaps two or three times as long, as I had to wrestle with what words I could use to rhyme and retain a loose meter while nonetheless conveying the image before me.) The contemplation becomes layered in trying to have both the means and the end of experience be conformed to a poetical manner of thinking. This, to my eye, is the reason for the superiority, though not the exclusivity, of formalism in poems in the restricted sense.

As I said at the outset, I do not believe that what I have provided here in any way dismisses the more relativistic understanding of poetry from having some pull. Indeed, a lack of formalism when used consciously can itself have a profound impact; what comes to mind for me is T. S. Eliot’s The Wasteland which self-consciously moves in and out of formal constraints depending on what is being represented. Nevertheless, even this demonstrates that Eliot knew what he was doing as opposed to the ways in which someone can write virtually anything and simply claim it as a poem. I think this misses the contemplation of the medium that goes along with the object of contemplation and, in a world so devoid of beauty, I must admit my aversion to neglecting the prospect of making things delightful at every possible turn.