Much of my time is spent on a university campus. To be a Christian in such a context often devolves into debates centered around merely speculative theology and philosophy, typically forwarded as a means of defending one’s faith. Especially in the broader culture of twenty-first-century North America – of which the universities are arguably the epicenters – these can be rather virulent exchanges, and I personally struggle with adequately engaging in these debates. There is a profound temptation to become dismissive, arrogant, indignant, uncharitable, or even hateful; when confronted with suggestions that one perceives to be evil and destructive, these reactions may appear more sympathetic but remain antithetical to the Christian way. Though a crime may be contextualized so that a man justifiably receives a lighter sentence, his guilt is not denied.

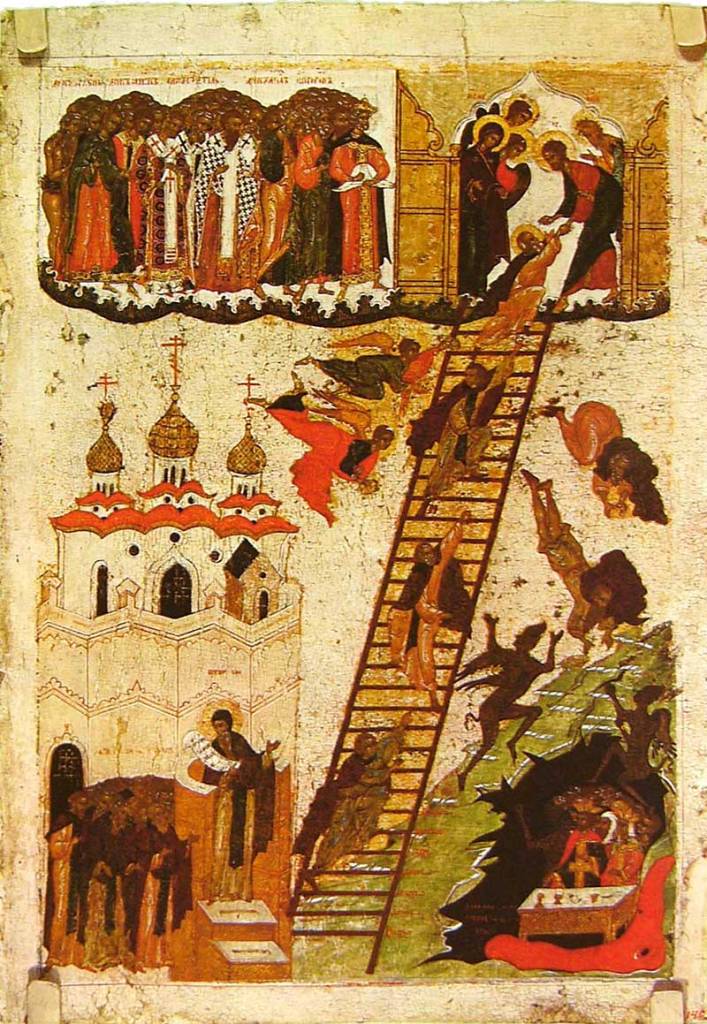

This tension has been weighing on me more heavily in the last few weeks, as we are now in the final week before Pascha (or Easter). During this time, it is a standard practice of the Byzantine Christian tradition to read The Ladder of Divine Ascent by St. John Climacus. This book was written by St. John in order to provide a guide for monks engaging in profound asceticism. For the lay believer living in the world, however, this text acts as a reminder of the spiritual struggle when brought to its maximum pitch; in this way, it may not necessarily be as instructive as it is for the monk, but the text nonetheless acts as a reminder to come back to the first principles of our Faith in order to consider the ways that the world may be pulling us away from the narrow, Divine path. The text is profoundly practical; it rarely engages with high-minded or speculative affairs. Instead, it focuses on living a sufficiently mournful, repentant, and prayerful life that is the only proper response to sin and the mercy of God revealed most fully in Christ Jesus.

I can only meagerly begin to unpack the wisdom of this book. St. John provides an unfathomable account of the human heart and how it moves; he connects the various sins in ways that reveal how we stumble so easily in to their traps; he provides concrete recommendations to understand how sin may eventually be avoided. Given with what I have herein begun, I wish to sit with and share some of what is contained in a shorter section of St. John’s text. The book is divided into thirty ‘steps,’ hence The Ladder, which the believer climbs in order to purify himself of the sinful passions and attain a state in which God may make him whole. I am looking to “Step 11: On Talkativeness and Silence,” which I hope will be relevant for obvious reasons.

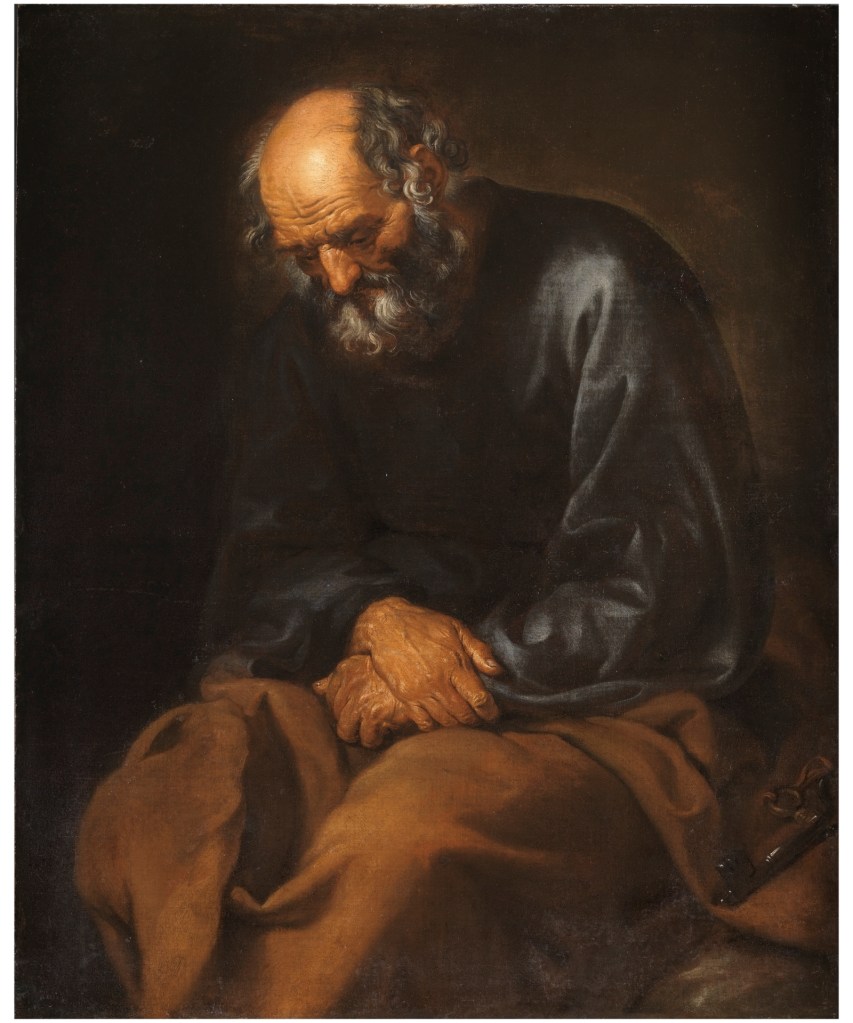

St. John is quite clear about his preference for silence over perpetual squabble: “Talkativeness is the throne of vainglory,” and “deliberate silence is the mother of prayer.” I think many people know the feeling of listening to someone and thinking that he may only be talking to hear the sound of his own voice – I am sure that I have made others think this many a time, and I moreover feel the performative contradiction in making this claim on a blog that no one has asked for. I recognize that there is a seemingly sinful tendency in such action as it implies one is better than others and should therefore be listened to. Conversely, one cannot genuinely listen to the needs and problems of another if he is so preoccupied with what he is planning to say; to genuinely listen to another implies the quieting of one’s own internal voice so as to fully open to the other – a great act of humility.

St. John goes yet further: “He who has become aware of his sins has controlled his tongue, but a talkative person has not yet got to know himself as he should.” The first clause suggests that there is a connection between recognition of one’s own shortcomings and silence. Who, in good conscience, enjoys giving advice on a subject which he does not have mastery of himself? Who can give advice to another on how to perfect himself when he is not himself perfect? This is a profound problem, though one that can also be abused and warped into a kind of relativism; maybe some silence would be good to avoid such steps into the ethical void – merciless and constant judgment may be the root of total moral breakdown. Perhaps fewer words provide the silent space for reflection that must follow argument if it is ever to avail.

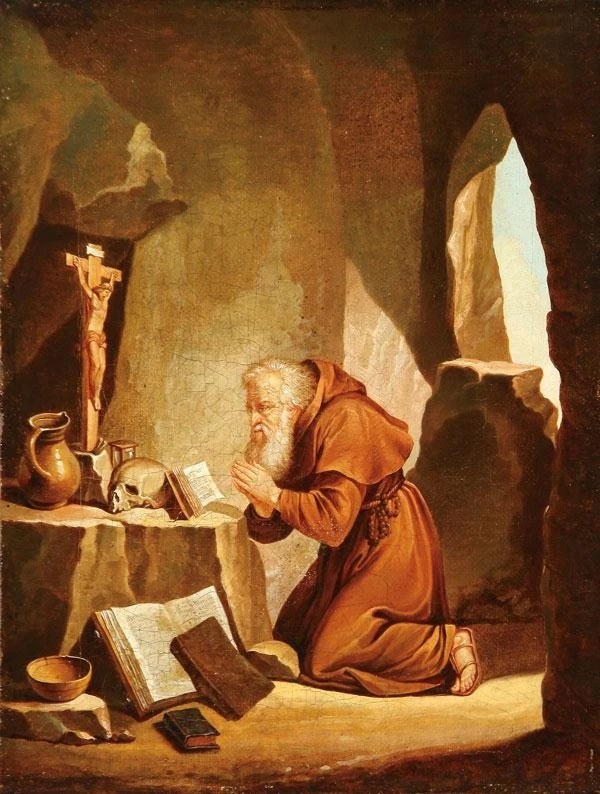

The second clause suggests something more unsettling. If I am always speaking, of what quality are my words? Who can perpetually speak and never say something either amiss or foolish? In his gospel, St. Matthew gives us just a sentence spoken by Christ before He flees into the desert for forty days – who am I to utter anything without also seeking such desolation? Moreover, there is a reality that must be faced: these words I utter are always being chosen, and they are being chosen by me. But who is this ‘me?’ What is he like? If he is the sort of person that says all the things I say, I do not think I like him very much; to become the sort of person that I tentatively take as being wise and prudent, I must guard my tongue and carefully discern the weight of each word that passes from my lips and becomes my self-disclosure to the world.

No doubt, such a movement towards silence requires a deep sense of Faith – “The friend of silence draws near to God and, by secretly conversing with Him, is enlightened by God.” This likely sounds like superstitious nonsense to those who do not pray or have a spiritual sense; even for those who do, this can be profoundly challenging. I, personally, struggle with silence. Blaise Pascal is famously quoted as having said that modern man’s problem is that he does not know how to sit still by himself for an hour. In many ways, I take this image from Pascal to be indicative of myself and as a profound sign that I am without true Faith. I always need to be doing something, listening to something, consuming something, thinking about something, as if I believe the various pains and strife in my life will be truly extinguished by something that I do – but what of this has saved me from continuing to sin or taken away the inevitability of death? Maybe such thinking is sin and death.

This, however, brings me back once more to the tension of speaking one’s Faith. Can I do so while remaining faithful? I think it possible, but I have conceived it poorly for a long time and usually still do. I think that, more often than not, the content of the argument is truly secondary to its form. What argument could I ever deliver that will take away all the pains of this world? There simply is no such argument, but there may be a way of conducting oneself in the argument that reveals something more. If anything, the moments of my own silence in such discussions might provide much more than any positive or affirmative content on my end of the exchanges. To have the patience and calm needed for such a manner of speaking, I must truly procure within myself – with the help of God’s grace – the belief that there is Someone far greater who is genuinely in control; to have such a gift calls us to share with others the delight and joy made possible by this knowledge despite all the tragedy and evil we know so well. And to know and say all I have said here is not to have done this.

As a last and perhaps disjunct note, I will give a brief story from a few year ago. I was sitting – as I often did – in a graduate student office, which was a large shared space with about a dozen desks. The graduate students would meet undergraduates there, work on their own projects, and frequently engage in conversation. It was a nice space. One day, several people of various faiths (or none) began talking about God and evil. Nearly everyone thought that this was a dire problem and that God needs to answer for what He has allowed to happen to us. This conversation went on for a couple of hours, and the quality of the commentary began to wane as the minutes ticked past. Eventually, one fellow simply blurted out, perhaps with a little but not enough sarcasm: “You know, I really do think that – if there is an afterlife – I am going to need a word with God before I settle into whatever He has planned.” I sat for a moment and thought that this was such a peculiar comment. What could you say to God that He doesn’t know?

I am (or should be, I daresay) speechless! 😏

Jest aside, an edifying and insightful piece—serendipitously received.

LikeLike

I am (or should be, I daresay) speechless! 😏

Jest aside, an edifying and insightful piece—serendipitously received.

LikeLiked by 1 person