The culture of our contemporary anglophone world, to my eye, seems ordered toward the ideal of ‘toleration.’ There is much wrapped up in this claim, but the general thrust is that we believe in some form of individualism and therefore want to allow each person to pursue life as he or she sees fit – so long as this does not hurt anyone else’s capacity to perform that same pursuit (we see quickly how this dovetails with notions of liberalism). A core aspect of this, at least that I have come across, is the constant petition to be “open minded.” This injunction manifests in other forms as well that I believe amount to the same proposition: protests against being “prejudiced,” the idea that we must fight “biases,” or – in more aggressive forms – that we must espouse a form of relativism (which, of course, makes the claim of toleration incoherent). In my view, all of this winds up devolving into a form of irrationalism. It cannot withstand scrutiny. I, therefore, want to pick at one aspect of it: the notion of ‘mind’ that is implied in us being “open minded.”

In a prior post, I referenced an essay by Michael Oakeshott entitled “Rational conduct,” found in his excellent collection Rationalism in politics and other essays (RP). The express aim of the essay is to clarify what we mean when we call something ‘rational’ or ‘irrational,’ though there is also a secondary theme that pervades the paper: a rejection of a seemingly modern notion of the ‘mind.’ In some sense, I take the latter, secondary claim to be Oakeshott’s more profound insight in the paper, though I take both to be worth reflecting on, as each demonstrates a clear problem with the ways that I believe we contemporary people tend to talk about ourselves and one another. Oakeshott’s position certainly informs what I am herein arguing, hence why I think it fair to direct you to his essay.

To be clear, my intent here is not so much to attack a colloquial manner of speaking, as I no doubt slip into language that my argument herein would seemingly run afoul of: “Oh, that slipped my mind”; “I’ll keep that in the back of my mind!”; “He has lost his mind!” I do think, however, that there are ways that we can retain these common forms of parlance but while having an understanding of them that does not maintain the errors that I am herein seeking to elucidate. My hope is that, if my critique of “open mindedness” and the ways we tend to speak of our ‘minds’ in general is well taken, we can better understand ourselves and reconsider various errant notions that tend to persist in our age.

To suggest where the problem emerged historically is largely beyond my capacities, though it does seem to be coeval with the emergence of the modern era and scientific thinking. I make this brief remark as I believe that there is certainly a way in which the ‘mind’ has developed into something that is thought to be merely in the heads of human beings, a mark of our modern ’empiricism’ seeking a ‘concrete’ notion of the mind; John and Sally are therefore each said to ‘have a mind,’ and we might even confuse the mind and the brain – a rather common problem within neuroscientific and psychological debates today. Moreover, this notion of mind has come to be thought of as a ‘faculty’ of the human person with a rather ambiguous status: in many ways, people speak as if it is like a muscle with a preset function and capacity waiting to be actualized; that mind is somehow a latent reality in the person until he or she disencumbers it from distraction; as if, somewhere in the brain, the mind and its capacities will be found and freed.

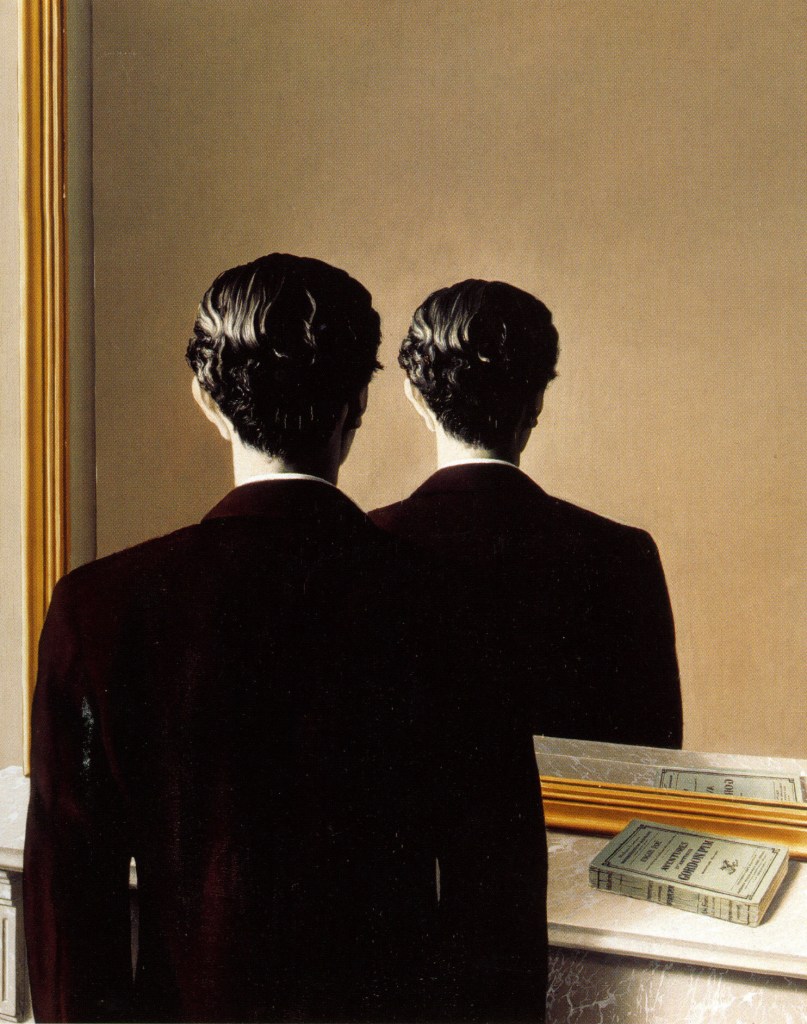

If this is the case, we might imagine that to have an “open mind” is akin to having an ’empty’ one. We can think of this once more on the analogy of the ‘mind’ being a muscle. If I wanted to move something heavy that required predominantly my legs to lift, I am unlikely to burden myself by also wearing heavy clothing and doing dozens of squats rights beforehand. In the same way, people seem to have an idea that a ‘mind’ that has been ’emptied’ of all other considerations is best for addressing some new problem or understanding a foreign concept. Oakeshott gives a rather direct example from C. D. Darlington that we should try to “teach children to use the English language but without encumbering their minds with English literature” (RP, p. 107). The presumption seems to be that to have a knowledge of what has come before and even to imitate it in some capacity is to burden oneself with things that are of ‘another mind,’ whereas we want to learn merely to use ‘our minds.’

Oakeshott’s lucidity in responding to this idea is paramount: “Now, this mind [as described] I consider to be a fiction; it is nothing more than a hypostasized activity. Mind as we know it is the offspring of knowledge and activity; it is composed entirely of thoughts” (RP, p. 109). Oakeshott argues that this is the case because one cannot even think if he or she is not engaged in a particular circumstance and activity. The mind as an empty faculty is nothing of utility, either in practice or in explanation. We might imagine a child playing with LEGO bricks being able to build many different structures by considering new ways of combining those bricks into new patterns. A child with a greater amount and variety of bricks is more likely to be successful in this endeavour because he has more to use and experiment with; in like manner, a student who has encountered and engaged with William Shakespeare, George Herbert, John Donne, John Milton, and T. S. Eliot will be more likely to have a strong grasp of English and poetry than another who has only ever read William Blake. The mind is built up through knowledge and experience, and it is not some sort of inherent reality that precedes knowledge.

It is for this reason that I think we must radically alter what it means to be “open minded.” In my experience, many people who call for this tend to mean something akin to rejecting what one knows so as to make room for another way of looking at the world – hence my earlier verbiage of ’emptying.’ This is, however, an impossibility, as to empty my mind would still be to exist in a position of pushing away what I know and assuming that what I am newly encountering is not what I know – in other words, what I know is still being factored into how I engage with the new thoughts or ideas, even if only in a negative sense (which I am doubtful of being entirely negative). Moreover, I believe that this call for ‘openness of mind’ actually betrays what is going on in such an exercise. What I believe people actually mean by being “open minded” is that they want people to give time and attention to something that may be different from what they have tended to encounter. What is critical about this is that such an exercise often requires a rather “full” mind, a mind that has engaged and thought through many other notions, in order to be able to handle a new, perhaps radically different, suggestion.

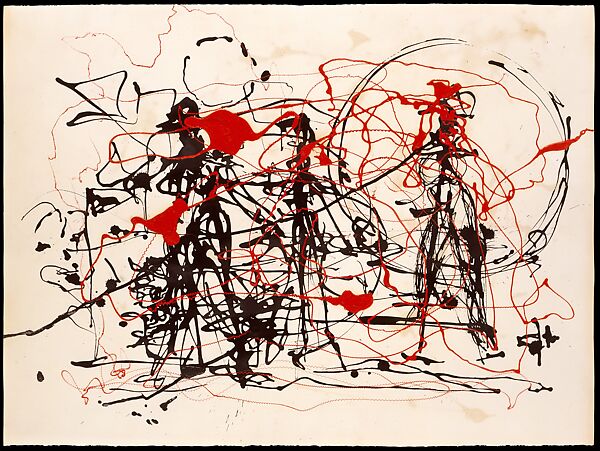

There is a myriad of examples that I could give for how our ‘minds’ work that makes the notion of an ’empty’ or ‘open’ mind irrational. If one were to learn to play blackjack, he will likely learn it more quickly and effectively if he already knows how to play crib, euchre, and Texas Hold ‘Em; if one is to learn how to play hockey, he is likely to better adapt to it if he already knows the rules of soccer, basketball, and football; someone could likely learn to paint more beautifully if he already knows the skills of drawing and sculpting. What we see in these examples is that knowledge is not a cumbrance to the mind but is rather its only means to being open to new things; indeed, knowledge is more accurately additive or cumulative, in the sense that it is a prerequisite for more adeptly encountering the new and unknown.

An additional aspect of this correction about the meaning of ‘mind’ and ‘knowledge’ is that it suggests that what we know and how we think is not merely something ‘in our heads,’ so-to-speak. Of course, there is the bodily aspect involved in so much of our knowledge – highlighted by things like knowing how to play a sport well – but there is also the fact that the reality beyond our merely psychological and physiological selves must be taken seriously. There is no such thing as ‘knowledge’ that does not, in some manner, contact with the world that exists beyond ourselves in our contingent limitations. In my view, the notion of ‘mind’ is better thought of as a property of Being itself, reality as such, which we then happen to be able to participate in through our given nature. This is the only way in which any form of knowledge – be it moral, scientific, historical, etc. – can be known.

Now, there may be different ‘ways’ or ‘modes’ in which mind may operate, but we have to carefully consider what this means. For example, we do have different sorts of knowledge, as just mentioned above, that might even overlap on top of one another – for instance, water can have different meanings and relevance to the scientist, historian, poet, or theologian. In these instances, we as the active agents may chose to engage with the world in different ways to enter these different modes of thinking, hence how a chemist may disengage from his research enterprise and go to Liturgy after work without contradiction. What must be recognized, however, is that in any form of engagement, thinking is not merely something that is within our heads but is a point of contact between us and the world. If this were not the case, there would be no difference between us ‘creating’ and ‘recognizing.’

As a final development, I would like to suggest that what we mean by mind is rather the logic of a certain way of engaging with the world that we find ourselves in. I think this is made clear by thinking about the world in scientific or historical ways, but I would suggest this also extends to the moral. When we refer to a ‘scientific mind,’ we think of a person who makes judgements that connect the many goings-on in the world together in a coherent manner, given certain presuppositions. A ‘historical mind’ would do the same, though the presuppositions involved would simply be different than that of the ‘scientific mind.’ ‘Mind,’ therefore, seems rather to be a property of the world that we can participate it; it is latent in experience and can be engaged in different ways, but it is not something merely in our heads nor is it some inherent faculty we have that we would be well to disencumber from all else.

Of course, we must recognize that we are beings that exist within the whole of reality, which appears to be an incredibly vast and rich world. To make the claim that we are always engaging with a real world that mediates our experience and is necessary for us to think does not mean that we have an unerring and absolute grasp of that reality with which we are engaging. We can always seek out a deeper sense of our experience by trying to think through and act in the world in a more fulsome and coherent way. In this situation, we would do well to be open to others and the perspectives and insights they may be able to share with us – an engagement that presupposes not an empty head but rather an agent filled with experiences and considerations that can help him adjudicate the claims of others and, hopefully, learn much from them.