Plato is well known to have composed his philosophical texts in a dialogue form. Most frequently, he places the historical person of Socrates in the center of his dialogues; the great philosopher who wrote nothing down then engages with various other historical characters, more or less antagonistically, depending on the dialogue, and questions them about many topics – usually predominantly featuring one in each text. The Euthyphro is a discussion about piety; the Protagoras is predominantly about virtue; and the Republic is famously an extended exercise in defining justice. Each of these topics is engaging, and Plato has much to say about the nature of Truth, Beauty, and Goodness, but – for now – I am more interested in reflecting upon his method.

The dialogical form can be a bit confusing to pin down. When I have taught introductory political theory courses under various professors, the undergraduate students tend to find Plato enjoyable to read but difficult to interpret. Most commonly, they cannot grasp what is distinctly Plato. There is often a looming question: is Plato simply to be associated with Socrates’s voice? Is Plato’s voice that of another character? Is Plato merely the writer of the dialogue as a whole and therefore stands over and above the entire dialogue? I tend to favour this last option, but then more questions abound: what about when the characters do not agree? Why feature Socrates so centrally and yet have him make mistakes? Why not just write a treatise that is the outcome of the dialogue?

I do not think there is a singular answer to this, but I will give one possible answer that could go along with many others: for Plato, the process of philosophizing is just as important as the various claims it generates. I remember once hearing that Seneca wrote in a letter somewhere that Plato, Aristotle, and the whole lot of Greek philosophers learned far more from Socrates’ conduct than they ever did from his teaching. To be a philosopher is not merely a destination but a way; it makes sense for Seneca himself to have emphasized this, as the Stoics were philosophers that often espoused teachings that strike the modern imagination as being more ‘religious’ and ‘practical.’ Among the ancient philosophers, philosophy was not merely a pursuit of the mind but an exercise that governed our very embodiment and conduct. For Plato, therefore, it was integral to embed the very process of philosophizing into his writings to act as an example; dialogue is the process of questioning with others and working one’s way around various questions to generate ever more fulsome answers (and, perhaps, incorporating more insights along the way).

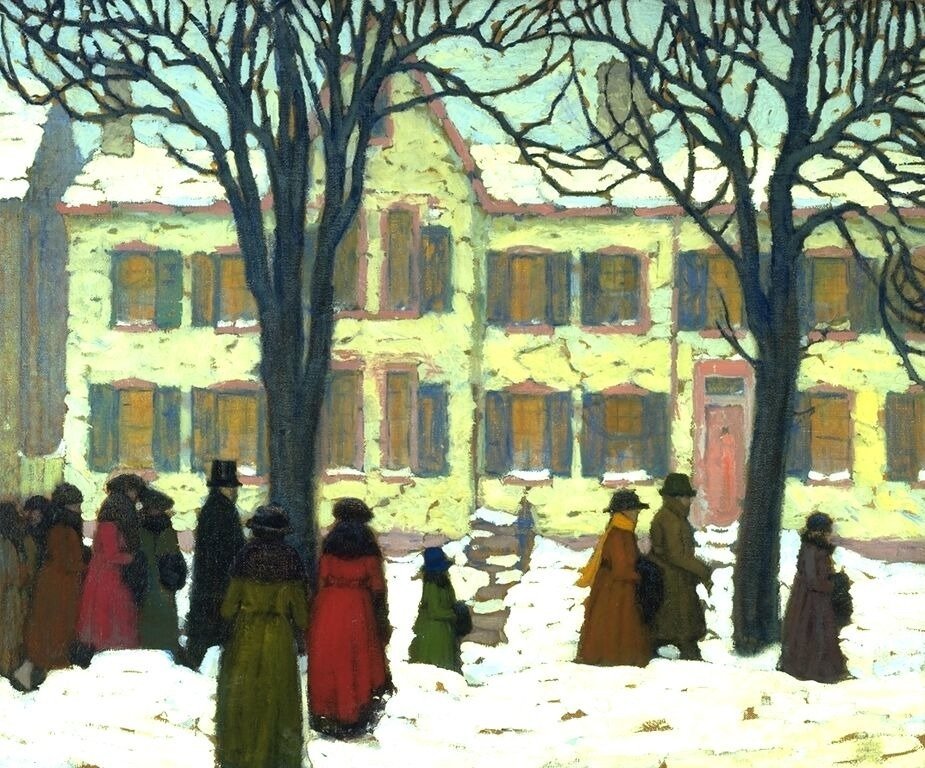

In the modern age, there has been a notion of ‘historical dialectics’ that has become somewhat unfashionable – though I still think it sits in the background of various people’s beliefs about the world. I will begin by first considering the view that many people still certainly hold – that of progress in history – and then explain how historical dialectics plays a part in that. Since approximately the eighteenth century, many people have believed that history has been progressing toward ever-improving social and political circumstances. To once more invoke my Canadian identity, one of our current Prime Minister’s famous claims during his first term is only made coherent by understanding it in the context of a ‘progressive philosophy’: Justin Trudeau, when asked why his governing Cabinet had a 50/50 gender parity responded, “Because it’s 2015.” Granted, there are also some vaguely feminist views bound up in this moment, but the idea is clear: ‘sexual equality’ is a form of progress, and the reason that equality has been achieved is because time has continued to pass. In other words, the mere passage of time suggests that things ought to be improving, and the corollary to this would also be that this is the best time to have ever been alive because it is the furthest progressed into the future.

Historical dialectic is merely a grander vision that is meant to undergird this progressive understanding of history, and it also helps to sort out some of the bugs in the naive view of history as progress. An obvious problem for the narrative that history is unending progress is that bad things still frequently occur, even in places where the evil of the actions was evidently known. The obvious events of note in the twentieth century were the mass killing of Jews under the Third Reich and the slaughter of millions by the various communistic (at least in some form) regimes of Russia, China, or Cambodia. Many could not understand how a progressive history could allow for such evil if things are only supposed to be getting better. The notion of historical dialectic helps here insofar as it allows for a greater trajectory to be posited: evil can still crop up its head, perhaps like never before, but it does this so that resistance can bring about an even better reality. Thus, the overall movement of history is still toward the better, but it also allows for a space wherein evil can still exist – and it even works that evil into the progressive movement toward the greater.

The resemblance between these brief overviews of dialectic in the Platonic sense and its later historical variant is obvious. In Plato, various characters propose various views about things, and through an engagement between the views, the most coherent and wholesome view can triumph through a kind of intellectual combat – or, at least, the original opinions are recognized to be insufficient. In the historical variant, this sort of clashing is made more practical and societal: various social or political movements arise, clash against one another (sometimes even generating great upheavals, chaos, and violence in the process), and then can settle into more coherent and true arrangements of how life should be lived.

I am, however, personally unconvinced by the myth of historical progress, including the possibility of a dialectical movement in history that could be at play. I have several problems with it, but I will give you the most cogent here: it erodes standards of morality, or a standard of morality corrupts the progressive narrative. In the first instance, if someone is so bullheaded as to think that the each proceeding day is inherently better than the last, he cannot then complain about anything – for this is the best that has ever been and the only standard we can measure against; conversely, and I think far more commonly (perhaps, actually, universally), people instead insert a criterion (or criteria) and argue that its ever greater presence in our society proves the progressive claim. There are many such criteria floating around today: equality, “democracy,” technology, medicine, science, etc. This latter option, though evidently being the saner on its face, has a clear problem: any changes that contravene the moral criteria would imply a degradation in history that cuts against the progressive narrative, and ostensibly the movement of history would not merely be the passage of time (as a progressive history might suggest) but rather an active movement toward the stated goal elucidated by the criterion. If such is the case, then, the moral claims are not merely able to be determined by recourse to ‘historical progress,’ but one must instead make the logical case for the supremacy of a certain moral criterion or a system of moral criteria.

Despite this criticism, however, I do believe that there is something to be said for this manner of thinking that is worth staying with for a moment. In fact, I believe that there is a way that historical knowledge can help to generate a deeper form of progress: but it is not as if the mere passage of time, the plodding on of history, is sufficient to explain ‘progress.’ Herein, I have to make a concession and then proceed to my suggestion, which I will do in that order.

I concede that progress can be granted if a value is posited – and, typically, this means it is a limited claim to some degree. For example, I think that the technology and medicine involved in birthing children has radically improved – progressed – in recent history, and I am deeply thankful for this. Medical researchers and workers having developed knowledge and techniques that have led to critical declines in mother and infant mortality rates – thanks be to God. But we will quickly notice that this claim does not emerge from some kind of historical reasoning itself. Instead, I have a clear moral judgement that is instead based on my views of human beings and the world we find ourselves in; one need not have profound – or, frankly, any – knowledge of history to know what is good, or at least have an intimation of it. One need not have a bachelor’s degree in history to know that comforting a small child who has fallen and scraped her knee is a good thing; moral reasoning is of a different sort than historical thought.

For now, I cannot get into the criteria that I think are integral to moral reasoning – though it largely has to do with the notion of what it means to be a human being and living that out in one’s particularity. I have pursued that topic to some degree in other posts, and I will continue to write about it, but it is not my interest here. Instead, I want to provide something of a revised possibility for a ‘dialectics of history.’ As opposed to conceiving the idea as an inevitability of the clashing of societies and cultural values over time that results in an ever-progressing society, I want to suggest that there is a way in which history can aid us in developing an even richer (albeit, more difficult and complex) dialectic that is more reminiscent of the Platonic variety. Historical work is most certainly involved, but it is merely necessary while also insufficient.

The various moral criteria that help us to envision ‘progress’ and, more directly, what is good are frequently developed in consultation with other people. I do not mean this merely in a cooperative sense wherein mere social agreement is helpful; rather, I mean that we all discuss ideas with one another in order to think through what is best and then make decisions. Indeed, having been married for a short period, I have learned that one of the greatest blessings in having a wife is that I have another person to check my deliberations with, specifically about difficult decisions I need to make. Having that dialogue helps me to think through what I intend to do and gain a greater perspective on the various risks, benefits, and alternatives to what I am thinking of doing because my wife is able to think through the same things and perhaps highlight things I missed or overlooked.

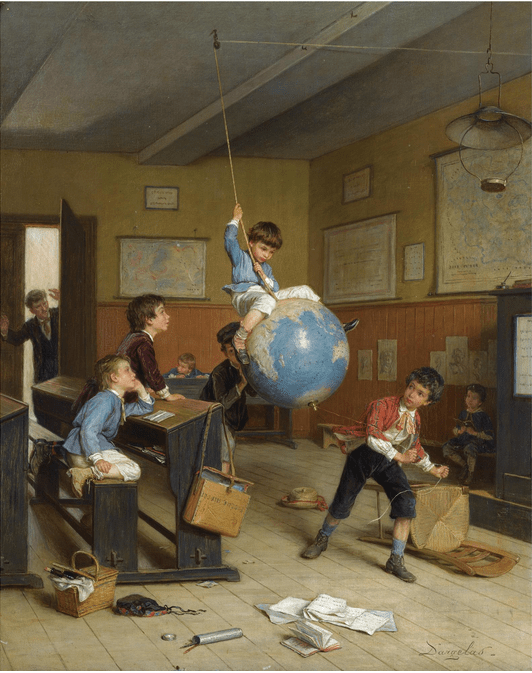

My suggestion, then, is that history provides us with a wealth of voices with whom we can engage in the hopes of entering a kind of intellectual dialectic. This is complicated, of course, by the fact that the necessary work to engage with these voices is quite different from moral or philosophical deliberation. There is a distinct, historical engagement that is required wherein one considers the thought of a past thinker with the goal of understanding how that person thought but without evaluating or criticizing what that person thought (this is a common error of undergraduate students; they wind up criticizing a figment of their imaginations only loosely associated with the figure in question). This act of constructing what a prior person thought is a possible engagement in itself; much work in ‘intellectual history’ is precisely performing this activity. Once this has been done, however, the constructed mind of the historical figure in question can then be ‘dialogued with,’ so-to-speak, in the sense that we can consider how they would respond to various issues. Yes, there is certainly the issue of mediating the differences in context, language, and time, but this is something we in fact do all the time.

What is evidently distinct about this view from that of the notion of a progressive, historical dialectic is that this form of thinking requires a conscious effort on the part of present-day thinkers, and those people must perform their task rigorously. Someone today must ensure that he is not merely corrupting his sources, that he argues the side of the figure with whom he is engaging against himself, and that he recognizes that the thinker may in fact be correct on things about which he will need to change his mind. In this way, historical personages can come alive once more and ‘engage’ in what is seemingly much more similar to a Platonic dialectic with contemporary thinkers. In this ‘dialectics of history,’ as I have briefly outlined it here, we expand our resources for thinking profoundly and widely about the various issues that afflict us – and which have afflicted many people throughout history. In this form, there is no guarantee of progress, but by engaging with the most impressive minds, present and past, we have a greater chance of improving our thought through the most rigorous sources our species has offered beyond those we can find merely in our current, local contexts.