For Z. H., a wonderful friend who asked me this horribly simple question

After having joined me for an evening prayer service, a friend of mine – who himself is without any strong religious affiliation – had a number of questions for me that we discussed over a couple beers. This began with simple technical details of the prayer, then proceeded to clarifying what a few of the phrases we use mean, and asking the occasional question about certain corporeal components of the services like bowing and so forth. These were all fairly easy to answer for someone who has a sufficient knowledge of their faith tradition and provided a good amount of discussion. Suddenly, however, my friend decided to ask a much more difficult question:

“Why do you pray?”

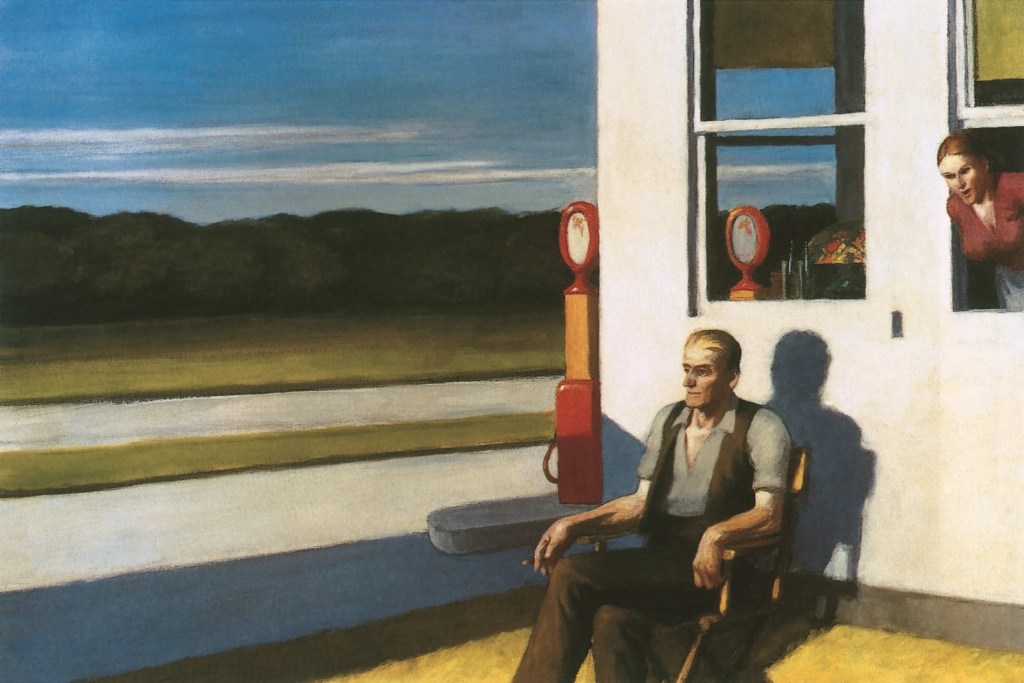

I did not have an immediate answer. I confessed to him that I almost did not understand the question. Why do I pray? Why do you eat? Because it is essential! But there I was, sharing a drink with a friend who was raised and, for the most part, still is largely ‘secular’ (though I find this term insufficient) in his approach to life. Moreover, my friend is a profoundly intelligent, well-mannered, caring person. How could he have managed to turn out so well in light of the fact that prayer is such a foreign concept to him? All this was running throughout my mind, but that meant that I was sitting in silence as my friend was still patiently awaiting an answer. He persisted: “What do you think prayer does?”

I did not have a good answer. I fumbled around for a few minutes trying to pull something together, but I have to admit that I simply failed. I did not provide a good answer; indeed, I barely gave an answer at all. Thankfully, my friend was rather gracious and seemed to just drop the concern, as I imagine he saw my confusion and thought it would be uncharitable to continue. Nevertheless, his question struck me deeply and has remained present in my mind for some time now – this conversation with him was, in fact, almost six months ago now. I have thought about this question weekly, if not daily, and I have only begun to form an answer. Herein is my tentative response which I write in the hopes of clarifying this for any reader, my aforementioned friend, and – perhaps most pertinently – for myself.

Prayer moves in a number of directions, and therefore finding the core of what a given prayer aims at is quite difficult. There are, just to name a few: petitionary prayers, thanksgiving prayers, intercessory prayers, etc. These all aim to do rather different things: a petition may be for continued natural abundance, a thanksgiving may be for another day of good health, or an intercession may be for a friend who is struggling to find a job. Now, these sorts of prayers all seem to aim at some thing: good crops, good health, a work placement. Taken on its face, this seems to be a rather facile practice, and one that some might even think would lead to neglect. There are ostensible ‘memes’ that have emerged now and then about this: ‘You have cancer – should we do chemotherapy or do you think grandma’s prayers are good enough?’ Obviously, this is shortsighted, but the message behind it is not entirely without merit. If the purpose is mere the obtaining of things or specific desires, then should we not just aim to do something directly? Should we not petition for more supportive agriculture policy, drink more water and eat healthily, and start making calls to get our friend some interviews?

Well, yes. Those things are all quite fine to pursue if they are within our reach – though we must recognize that not everyone is necessarily capable of all these things. The claim here about prayer need not be an either/or; we can pray and perform certain actions to realise a given end. From the position of the believer, we do tend to think that God moves in the world and therefore may enact something through our prayers; but, even for those who are not convinced of this, I believe that the mere ‘well-wishing’ for the other implied in the prayer is desirable, as it acts as a kind of reminder to live in the love and remembrance of the pains that those we know are going through. At minimum, prayer can transform the heart of the one who prays to be more loving and supportive to those around them.

I believe that there is, however, a deeper reality to be acknowledged about prayer that is present even in these simplistic examples that I have provided: the recognition that something is wrong. Now, what is meant by this is not easy to unpack, and I believe that this was, in some sense, my stumbling block when I first tried to express what I believe prayer is to my friend. The Christian way of explaining this is to refer to the Fall, the first sin, and recognize that humanity is living in a circumstance where all is not well – and, in some way, we are contributing to this problem. Yet, we also certainly have a sense of how things could be made better, that things should be otherwise. The logical implication of this is that the world could, in theory, be perfect; we could live in a circumstance where nothing is wrong.

That last statement may sound somewhat utopian in orientation, so it must therefore be reigned in as that is hardly my intention or belief. The human being is only a part of Creation, of the world, and is not therefore aware or understanding the whole of Being; no doubt, we have a rational faculty, but we do not have control over everything and occupy a rather limited station. This is one reason why Genesis depicts the Fall of Humanity coming after Adam and Eve eat of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. To echo in a radically deficient manner the thought of St. Gregory of Nyssa: eating of the fruit of this Tree was not so much a sin because of some substance in the fruit causing death (though this may still have some intrigue) but is rather because the indulging in the fruit indicates a shift in man’s heart that divorces him from God insofar as this action indicates that man no longer trusts in his Creator and instead believes that he can think and connive himself into perfection – a folly given the enormity of Being and our impossibly small place within that reality.

Now, perhaps some, especially those of a philosophical orientation – specifically in the manner of ancient Greeks – will reject this and argue that we can in fact achieve a kind of total union with existence via our intellectual faculties. I, however, am not convinced by this; I also detect in several of the ancients a skepticism about this being fully realized – one that can even be found in Plato, perhaps the greatest promulgator of Socrates’s thought that suggests this manner of ‘philosophic life.’ My main critique of this position is that it involves just as much ‘faith’ as the man of religion (for belief in the rational intelligibility of the world must be maintained before it can be proven, or the philosophic pursuit can never begin) and that I do not find the idea that man, as a mere aspect of Being, can understand Being in its entirety. What supplements this is a Faith, a reasonable Faith, predicated on the recognition that things do seem to be reasonably ordered but far beyond my grasp; I therefore trust in Being, beyond Being to its Source, in the hopes that it (or, more accurately, He) will direct me in the manner that I ought to live within this grand Creation. This is the essence of prayer: to live in this disposition of trust.

This is why, when I myself pray for someone or something, I rarely demand something from God. Instead, I tend to pray in a rather couched manner. An example here is illustrative. If I have a family member who is struggling with something profound, perhaps some form of terrible illness or even the possibility of death, I do not pray, “God, heal my family member X“; instead, I tend to say something more like this: “God, please heal my family member X‘s pains and illness, insofar as it be according to your will, and give those of us who love X the strength and wisdom to bring about what you desire.” In this way, I believe the intent of the prayer is quite different, as I am not presuming to know what the good is but am rather giving myself and my will over to whatever it is that the Source of all Being intends and trusting Him – because, as far as I can tell, we have no choice if we wish to be fully ourselves.

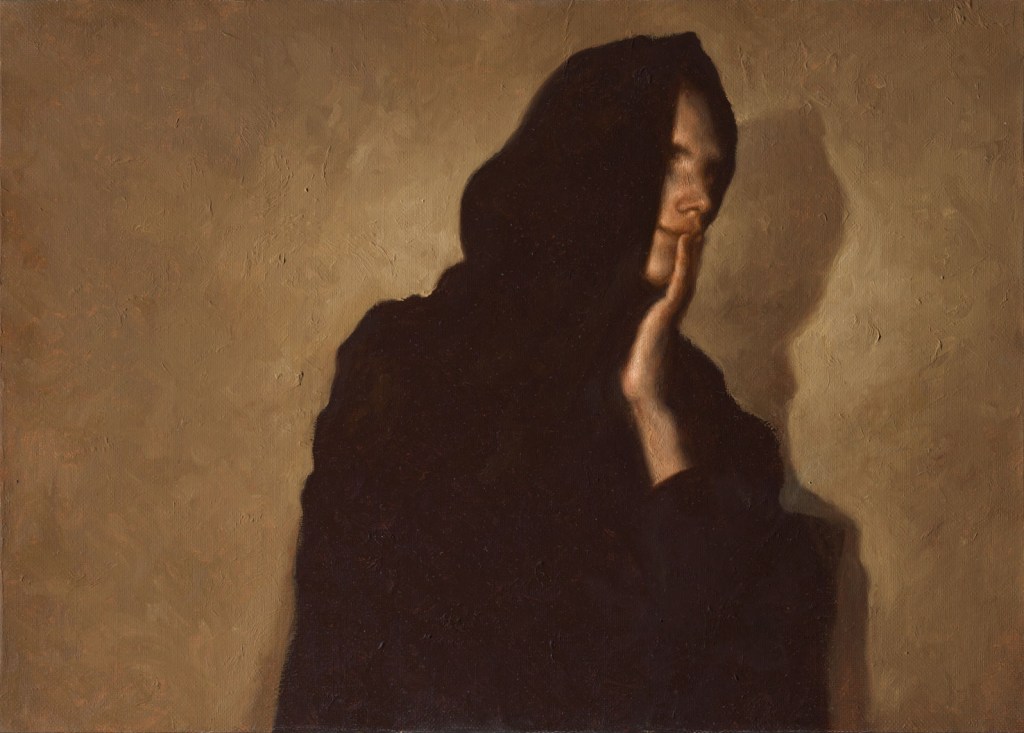

I recognize that what I have provided here is only the beginning of an answer, but I hope one that will provide the unfamiliar or – if I may be so bold – even the doubtful to reconsider the nature of prayer. There is a deep history of reflection on prayer in the Christian tradition alone, though I know that there is more to be found in other religious traditions. All I hope to have given here is the inclination that prayer is something that is enacted in all things; it is not merely a moment, though there are times when explicit prayer brings something specific to the fore of one’s intention and heart. In some sense, I believe that regarding prayer as a kind of thinking is actually quite backward; rather, thinking is a form of prayer – prayer being the sustaining relationship we attempt to maintain with the fullness of Being, the Source beyond Being, in the hopes of experiencing life as it is meant to be. I think many people in fact inhabit this disposition quietly and indistinctly (I myself am often in this state), without a full-throated religious conviction, and therefore appear to be no different than he who prays often; but such appearances reveal not the interior of the heart, the vision of which is a rare gift, both to oneself and even more to the other.

Rejoice always, pray constantly, give thanks in all circumstance;

for this is the will of God in Christ Jesus for you.

1 Thessalonians 5:16-18