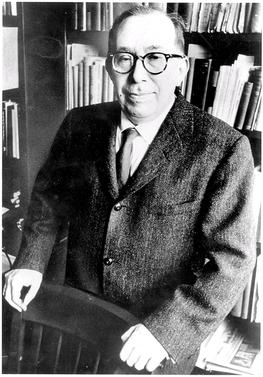

I have recently had the pleasure of returning to the work of Leo Strauss, a man who has become somewhat unfashionable in universities despite having much purchase throughout the last half century. The precise reason for why he has been cast aside by many is not quite clear to me, though perhaps it has to do with one of his main preoccupations being that of taking religion quite seriously. This is mere conjecture, but nevertheless I think it may have some merit – it is a topic that could in itself make for some interesting reflections. Nevertheless, such a debate is not my present interest. Instead, I am concerned with the idea that revelation and belief is something that people can avoid or overcome – I think that such a view is rather misguided and not reflective of our experience.

Specifically, I am provoked by one of Strauss’s essays, “Progress or Return?” The essay focuses squarely on outlining a perceived tension that Strauss believes sits at the heart of “Western” civilization: that between ‘Jerusalem and Athens,’ or, less metaphorically, between Biblical Revelation and Greek Philosophical Reason. To radically oversimplify the essay, the thrust of the analysis centers on the fact that both Hebraic Revelation and Greek Reason claim to be in pursuit of and making their way toward the One Truth, which could otherwise be called ‘God’ – but we ought not let the fact that both systems admit of such a divine category to allow our own equivocation of these endeavours. Strauss argues that there is a fundamental conflict between them and neither can become dominant. This, as outlined in the essay, is – to borrow a Nietzschean phrase – the creative tension that has sat beneath European culture and its offshoots for the last two thousand or so years. (There is an additional key theme to the paper which is that modern thought has largely neglected this tension; though this is both provocative and perhaps true, I will largely leave this untreated here.)

I have several objections to Strauss’s view. One is that he believes that his return to these “roots” of “Western” civilization are somehow necessary to healing many ills that he sees in the modern World. “Progress or Return” is based on lectures from 1952, and Strauss wants to demonstrate that modernity has somehow erred in its certainties – particularly in its certainty that we are progressing beyond all that has come before. Hence, we arrive at his desire to ‘return.’ Yet, what he skips over is the very historical lineage that allows him to refer to this entity he calls the “West”; at the heart of that lineage is the Christian Faith, and, though he acknowledges its existence, he does not seem to contend with its claims that extend beyond the merely Jewish understanding of Revelation. In any event, Strauss himself was of Jewish lineage and this perspective may therefore be chalked up to a personal detail in some sense (though I think that is hardly an exhaustive response).

More problematic, however, is Strauss’s presentation of ‘philosophy,’ the Reason of the Greeks. For one thing, presenting this as a monolithic worldview is an error. As demonstrated by Heidegger, the fragments that remain of Pre-Socratic philosophy indicate rather stark divergences existing within Hellenic thought; moreover, one can even perceive rather stark gaps between Plato and Aristotle. Aristotle’s writings, as handed down by posterity, do have a flavour of and are often read as being quite certain and, in some sense, ‘final.’ There is a mental rigor and power to the writings wherein Aristotle has generated a total view of the cosmos; his thought is ‘complete’ in some unique sense. This stands in stark contrast to Plato who had a dynamic vision of the play between myth and reason, who thought of contemplation as a seemingly unending ascent. With all this in mind, it seems to me legitimate to ask, ‘Which Greek’s reason are you referring to? Why that one? What makes it pivotal?’

Continuing on this issue, Strauss posits that Greek reason is, in some sense, contrary to revelation, Hebraic or otherwise. For him, there seems to be a deep naturalism to Greek thought, perhaps epitomized by Plato’s Socrates claiming to have only human wisdom, not divine. Revelation is therefore positioned as being ‘divine wisdom’ in this dichotomy between reason and revelation; again, this strikes me as somewhat peculiar. For one, the revelations to the Israelites do not seem to me to be not ‘human wisdom’; one could easily conceptualize the Ten Commandments as the human understanding of God’s directives. In some sense, I would suggest that Strauss is creating a distinction that is difficult to sustain. Second, it becomes difficult to sift out what is revelation from a more phenomenological perspective. I, reading today, might consider Plato’s thought so foreign and profound so as to be relevatory; as well, there has been such profound theology built up around given ‘revelations’ that they might now seem simply reasonable. Think of the fact that God had to ‘reveal’ to Moses that a murder ought to be prohibited – is not such a thought also considered natural in some way?

Strauss does, I believe, actually appreciate this problem in some sense. In the second section of “Progress or Return,” he recognizes that both philosophy and theology are locked in a profound tension. Revelation seems to devolve into argument – take, for example, Christians and Muslims arguing over their divergent revelatory books. It seems, therefore, that revelation begins to transform into reason. Conversely, however, reason does not have the capacity to preclude revelation because it could only do so if it possessed complete knowledge – but this would make the very striving of the philosopher unnecessary, and therefore the honest philosopher must stop himself from simply rejecting revelation. I think, however, that Strauss does not take this recognition of philosophy’s limitation seriously enough; in some sense, we must recognize that every form of reasoning must begin with some ground – some intuition, what we might call a hunch, what religions have called a belief – in order to get itself going. Even Plato’s system relies on the belief that the world is intelligible at its core – though we must inherently remain agnostic, at least in the beginning, as to the capacity of men to comprehend that whole.

We have now arrived at what is perhaps a more direct question: what should our starting assumption be? It seems to me, in some sense, that this is - at least phenomenologically – prior to the adherence to philosophy, religion, or anything at all. One cannot even look at the world if one does not understand what one is looking for, even if only dimly. Here, I believe that we better understand the difference between philosophy and religion: philosophy, in the Greek sense, begins by trying to understand the world, whereas religion – at least in its Biblical variety – begins with trying to understand oneself. The former – philosophy – can manifest in a wide variety of studies, as evidenced by the plurality of subjects contained in Aristotle’s corpus (even if some are rather underdeveloped). This appears to be true of nearly all the Greek philosophers, pre-Socratic and post-Socratic, as they posited certain answers to the question of being: many of the pre-Socratic sought the fundamental matter of existence in order to understand it, while others – namely Plato and his students – posited a world of ‘forms’ that acted as the guiding reality of matter (indeed, matter without form is unintelligible). It is important that I am not herein claiming that they have the same worldview but that their method of uncovering what it means to be a human being follows similar lines: understand the cosmos. The latter – ‘religions’ and their revelations – tend to emerge out of introspection; there is some kind of intuition that the world is not right, but this implies a looking inward toward the one who is doing the thinking. Anyone who does this earnestly finds incoherence and cacophony. Yet, simultaneously, this inward turn itself seems to begin sorting through such disorder; once this movement begins, the self begins to question its own being in order to understand what is wrong with itself. This peculiar process, however, has all kinds of bizarre implications: things were meant to be otherwise, there is something of an order to oneself that has gone awry, and therefore one must look for a remedy for their situation.

This is, self-evidently, too cursory to be exhaustive or even approaching satisfactory. Nevertheless, I will say one thing: I believe the religious impetus is more coherent. This was something that Socrates, our archetypal philosopher, curiously knew as he parroted the oracle at Delphi: Know Thyself. (How interesting that he had to be told this by an oracle?) It seems to me that religion begins in the recognition, perhaps an inspired one, that I must consider myself before all else, for if I seek order in the world despite myself being disordered, what could I ever hope to find? This is not some solipsistic or individualistic suggestion: this is the recognition that I am the problem to understanding both myself and the world. Now, of course, there are many different answers to this question: the world religions all differ in a variety of ways on this front, but I believe that we all begin with this recognition that we are the problem and some correction is in order – and this is true even of the ‘philosophers’ in Ancient Greece. We all therefore seek answers about where to find our reconciliation with being and to live in accordance with that order insofar as we can understand and adhere to it.

In short, what I hope to have suggested here is that we all live with faith – there are no ‘philosophers’ in Strauss’s sense. I have often heard people claim that G. K. Chesterton (though I have not yet found this quotation) said something to this effect: ‘There are those who know their creed and act upon it, and there are those who do not know their creed and act upon it.’ We human beings always have beliefs about who we are and what we ought to be doing; in some sense, we act out what we understand ourselves to be. Yet so often this devolves into chaos and turmoil and we realise that something is wrong with how we understand ourselves and the world, and then we must reconsider these views – this is, indeed, the perpetual struggle of the human condition: we have to understand ourselves but can never be beyond ourselves. We therefore struggle in our very being, but religions hold out the hope that Being can speak to us in various ways that relieve some of the turmoil.