For Fr. Dcn. A. P. W. B.

I have a friend who loves to tell a story about a phrase he heard from His Eminence, Cardinal Collins, at a dinner party: “We must remember that a human being is a ‘who’ and not a ‘what,’ a subject to be valued, not an object to be used.” I believe many of our current social ills are summarized in this succinct phrase stated by His Eminence; however, I think that it is equally problematic to claim that we can again understand each human person as a who and not a what through a mere substitution of terms. I think that this problem requires more thorough probing so as to question how the human person came to be seen as merely a what. In my view, the human person being seen as a what and not a who is not our problem itself; the real enemy is a competing cosmology that informs our understanding of the human person—one with which I believe the Christian must grapple should he hope to maintain his footing in the world today. I believe that this competing cosmology is technological—which we may juxtapose with Christological—and that to understand the risks it imposes, we ought to turn to a great Canadian philosopher of the 20th Century: George Grant.

When we think about ‘technology’—a noun that must be taken as distinct from the qualifying term technological—we are likely to consider our laptops, smartphones, perhaps our cars, or several other gadgets that we have at our disposal that allow us to do certain things that would otherwise be quite difficult, if not impossible. Typically, we pay little attention to these things aside from the first two or three days after we purchase them and are excited by all the new features of our updated devices—though there is perhaps the exception of paying attention to them when they refuse to work in the way that we desire. Nevertheless, Prof. Grant observes that we exhibit a ubiquitous complacency toward the technological developments and capacities that surround us, and he argues that we modern people are often blind to the reality of what is going on around us. To explain his position, Grant gives an example of something he heard from a computer scientist about technology: “The computer does not impose on us the ways it should be used.” In pulling apart this claim made by the computer scientist, Prof. Grant reveals how such a prevalence of technology has resulted in a form of technological living that obscures the reality of how technology relates to us.

The computer scientist’s claim implies that there are “values” that may or may not be imposed upon the computer to make it perform certain functions; this is what it means to say that the computer does not impose values, though we use it by enacting our own values through it. In our present context, we may find it quite easy to consider some examples of both the good and the evil that have become possible due to the advent of the computer. On the positive side, a young, impoverished child with minimal access to formalized education may discover an online world of learning in which his innate gifts for medicine or some other discipline are able to flourish; conversely, however, that same child may be subject to an online universe rife with predatory adults who will manipulate him into any number of damaging engagements such as financial scamming, political or social radicalization, or some form of sexual abuse unknown before the web. What the computer scientist is claiming about such a reality is that such good and bad outcomes are not determined by the computer itself, and therefore it cannot be considered as contributing to a better or worse world. What Grant observes, however, is that this claim being made by the computer scientist treats the computer as if it is merely something ‘found in the world,’ no different than the Sun in the sky or a tree at the park.

Grant attacks this view for being historically superficial and, perhaps, even wilfully stupid. What the computer scientist fails to acknowledge is that the computer was something constructed by humans to achieve a further goal; in so treating it as something that we consider ‘natural’ like a plant or a stone, Grant believes that the computer scientist has simply failed to understand what the computer is in its essence. Grant shifts the conversation by arguing that we must understand the computer as a development in what humans have constructed to use for various, further purposes—it is not simply something ‘found in the world.’ We may then ask: for what purposes did we construct the computer?

Grant’s answer to this question boils down to a recognition that all technological devices emerge out of a desire to control. We need not consider this in a merely pejorative way; we can acknowledge that certain kinds of control are perfectly justified and perhaps even laudable. We might consider the control found in the domain of medical technology to be a virtue in many regards. The ways in which cancer treatment has progressed due to our better control of various aspects of our bodies and knowing how our bodies will react to certain sorts of treatment are certainly things for which we ought to be grateful. With this perceived improvement, however, we are obliged to see that there are relevant risks. The example that unfortunately comes to mind at present, in our time of the COVID-19 pandemic, is that of virology. Evidently, this combination of scientific inquiry and practical application has led to increased disease control which has saved thousands or even millions of lives; yet, with the improvement of this field inquiry, we must also confront the possibility of creating illnesses that are far deadlier than anything we would find occurring without our impositions upon nature—something we pursue out of a desire to ‘get ahead’ of the viruses that the organic world may throw at us in the future (and this is a charitable view—we are not yet considering the possible malice of some person or entity seeking to create some sort of new biological weapon).

We will note at this point that the essence of such technological activity, therefore, is not merely to do good; though the benevolent researcher of the flu may desire to choose a good course of action, this is not necessarily what technology offers. Instead, Grant suggests that the essence of technology is revealed in looking to the Greek roots of what the term itself means: tekne (τέχνη) and logos (λόγος). Tekne can be understood as something like ‘craft’ or ‘trade,’ wherein there is a certain manner of transforming some aspect of the world by human volition; the common forms of this that would have existed among the ancient Greeks but which are still familiar to us today would be activities like stone masonry, carpentry, or black smithery. Logos, on the other hand, has a variety of translations, though the most critical for our present inquiry is that of ‘reason.’ This is the clear parent word of English terms such as logic, and its meaning can be seen clearly in other examples like ‘biology’: it is the logic of the bios, the Greek word for life. The term technology therefore means something like the ‘logic of crafts’ or, more poignantly, ‘the reasons pertaining to transformation by human intervention.’ In that latter definition, we see what Grant is aiming to have us acknowledge in the meaning of technology: it is not merely a means to do the good, but it is rather a means to have more means toward an indeterminate goal. Stated more pessimistically: technology is the study of how to control for its own sake.

We have thus arrived at the conclusion of Grant’s subtle interrogation of the ignorance latent in the computer scientist’s phrase that the computer does not impose upon us what it shall be used for: though perhaps superficially true, the computer scientist’s claim hides that the mere presence of the computer presents us with a circumstance in which there is the possibility of a deeper striving for control. In calling our present civilization “technological,” Grant is suggesting that we have become a culture enamoured less with doing the good and more with striving toward doing whatever we find that we are capable of doing—a set of possibilities that is ever growing with the continuous advent of new and progressively more powerful technologies.

What Grant sees in the modern world with such lucidity—and is therefore worthy of our attention—is that improvements in technology, powered by advancements in scientific knowledge, have the capacity to transform the world in such incredible ways that there seems to be no limit to what may come of it—except, perhaps, the limits of human imagination. This statement itself implies a rather radical view, however, and to miss the danger in this is to be naïve. In existing in a world that is constantly modified by the very technologies created by human beings, the modern person believes that nearly anything can be done, any impediment overcome, through the continued ‘progress’ of technology. At this point, we have approached something of a cosmological claim about the way mankind relates himself to the world. As stated so clearly by Max Weber: our modern, technological dogma is defined by “the conviction that if only we wished to understand [the conditions of the world] we could do so at any time. It means that in principle, then, we are not ruled by mysterious, unpredictable forces, but that, on the contrary, we can in in principle control everything by means of calculation.” We must recognise this description of how modern man views the cosmos as what it is: not a scientific or technological claim, but a spiritual claim. It is a statement of belief; no one can fully prove that this is the way things are, but one does have the reasonable grounds—given the world we live in—to make such an extrapolation.

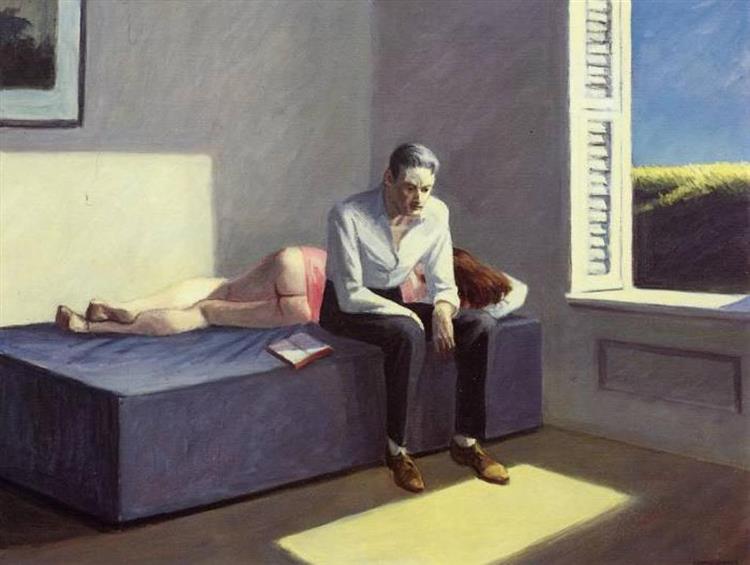

We can now return to the statement from Cardinal Collins from which this inquiry began. Insofar as we engage in this technological cosmology, we will see the world around us, including the people that inhabit it, as merely things to be modified and transformed at our will. To acknowledge the personhood of another is to concede that my own will and imagination are not the standards by which I can judge my conduct; it is to acknowledge that there are aspects to reality that are beyond my capacity to change and to which I must ascent. But the technological cosmology cannot acknowledge this—its very essence is the belief that anything can be modified to adhere with what I will. Manipulation usurps cooperation; utility replaces friendship; lust destroys love. It is not as if such treatment of the human person a what emerges from the explicit desire to neglect the inherence of human dignity, but it is rather the necessary outcome of a life lived in pursuit of control—something which, conscious or not, occurs for us human beings who are constantly surrounded by technology and influenced by technological thinking.

Now, I acknowledge that what I have outlined here, through the work of George Grant, may seem somewhat hyperbolic. There is something about it that seems incorrect since there is no one who thinks in an entirely technological manner in all that he does. I certainly do not believe that I have ever met someone who thinks in this manner in all aspects of his life (nor do I think it is actually possible). Indeed, I think the Cardinal’s statement that “a human person is a ‘who’ and not a ‘what’,” does not imply that we are continuously seeing our fellow human being as a what, but rather that our understanding of the human person is occasionally corrupted by specific circumstances—albeit such instances are becoming more common in our present culture. While admitting this, I nevertheless believe we must thoroughly think through this technological cosmology with great care, as it evidently has power within several contested issues of contemporary, public life. When we consider issues such as vaccines & illness, abortion, euthanasia, transgenderism, relations between the sexes, and more, there is an ever-present concern with our capacity to control. I want to be clear that I am not saying that these issues always have clear-cut answers, or that those who make claims from a standpoint of technological control are always in the wrong. To repeat what I have already stated above, we must acknowledge that control is not itself the problem, but control for its own sake is what is corrosive and leads to our own dehumanization. We must recognize that technology is always secondary to an order that extends beyond our capacity to modify, and our primary interest should be in coming to understand the nature of the foundational order in which we happen to find ourselves.

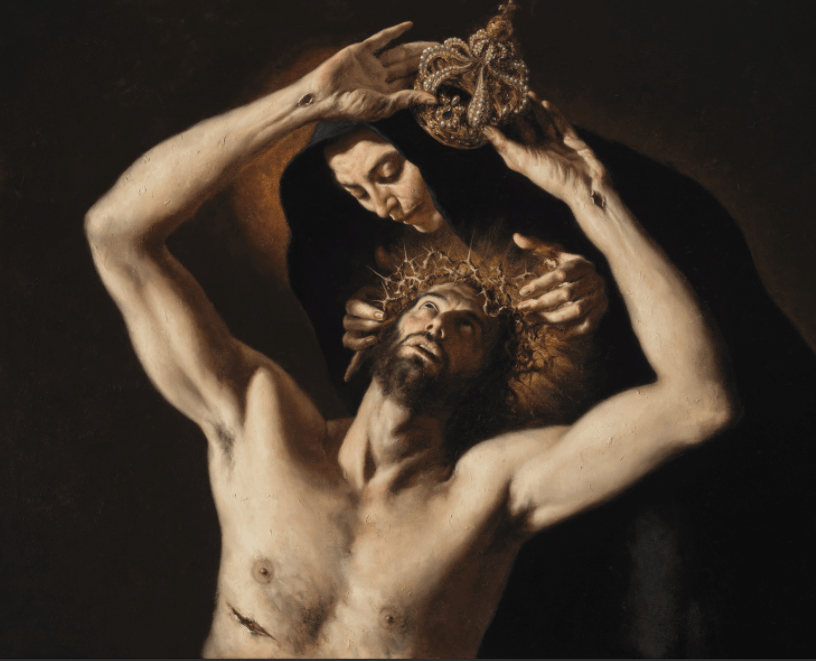

To paraphrase a line from the Confessions of the great St. Augustine: the will of God is such that a mind against His order is its own punishment. Yet, so long as we allow technological ways of thinking and living to dominate us, we can admit of no such order from a higher source; the technological man must ever stand athwart a received order, as it may contradict his capacity to control. But—if St. Augustine is correct on this, as I believe he is—the technological man will suffer twice: once because he has not aligned himself with God, and a second time because he has also blinded himself from the possibility of perceiving the true antidote to the ills of our fallen human condition. The Christian person, on the other hand, understands that the essence of what it means to be a human being is not something defined by us, but it is instead something that we come to understand as already being made for us. As followers of the Son of God, we believe that the fullest understanding of our place in the cosmos comes to us through engaging in a relationship with Jesus Christ—He who shows us what it means for the fullness of man and the fullness of God, the source of all Being, to come together. We ought to relinquish this illusion of control for, in reality, we have none. It is our acceptance of this truth for which Our Lord patiently waits, at which point He will begin to enrich our lives in ways we could never have imagined.

I wondered why your writing was so bad and then I realised you have your head stuck so far up your own ass that it’s too dark for you to read

LikeLike

If you are just going to insult me without ever addressing the content, at least make your insults original. Try to at least be intelligent or entertaining in the future; stop wasting our time.

LikeLike