This post is meant to be the first in a set of posts to come—posts I have certainly not written. I merely put this as a preamble for anyone interested in the topic(s) I hope to continue discussing, both to help give a slight backdrop to said posts and explain how I see these intellectual movements we have come to call Idealism and, more specifically, British Idealism.

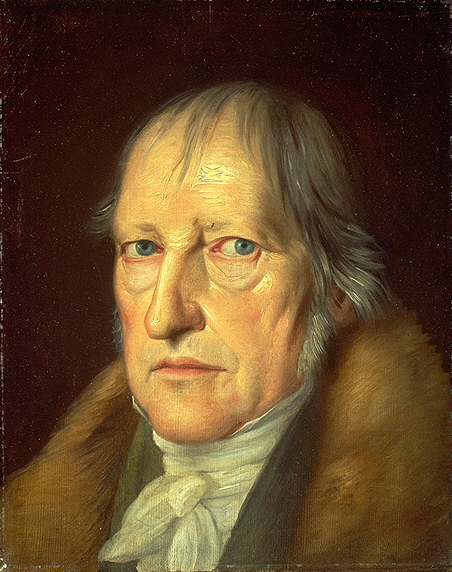

I do not think it a dramatic claim that the last two and a half centuries of philosophy in the “Western” world have been dominated by disputes around what has become known as ‘Idealism.’ The key figure in this narrative is typically considered to be G. W. F. Hegel, a German philosopher of great prominence in the early 19th century. In fields of politics and history, I think it a fair claim that he is second to none in terms of his prominence within the conversation about these domains. The discipline of philosophy itself has, as far as I can tell, been less influenced by his work—as movements such as pragmatism, positivism, and analytical philosophy entirely oppose him—though many of today’s “philosophers” still in some way owe a debt to Hegel even if they do not reside within an ‘Idealist’ camp.

What precisely Idealism is can, truthfully, be quite problematic to pin down. I would argue that its central feature is considering the relationship between abstractions and what may be called the Absolute, Experience, Consciousness, or perhaps even Being, though that final one may be disputed. (Was Heidegger an idealist of sorts? This would go toward clearing up the dispute.) What is typically meant by these terms, so far as I can manage to describe it, it something like the totality of reality in its completeness; as if reality in its entirety can be comprehended without any assumptions, ‘brute facts,’ or divisions within itself. Understanding this term in contradistinction to abstraction is quite useful. To “abstract” something is to remove it in some manner, whether practically or theoretically, from the greater whole within which it exists. Though this may be an odd use of language, one may say, “I abstracted a sample of water from the river for chemical analyses.” Of course, what he means is that he took a portion away from its broader whole in order to analyse it with more ease. The process of abstraction simplifies the problem so that only a portion of it may be considered as opposed to dealing with the whole all at once, i.e. the entire river per this example.

Of course, the risk in abstraction is always that what has been abstracted will cause misunderstandings due to its being removed from the relevant context. Coming back to the aforementioned sample of the river water, there is always the risk that a particular sample may be, by mere chance, not representative of the river as a whole. Perhaps the sample just happened to have a higher or lower chemical presence than the greater river, meaning that the abstraction was not representative of the whole and would misinform anyone who tried to use the findings of that data for some purpose. (Just as a note: repetition within empirical methods could attempt to overcome this, both by sourcing from multiple locations and on multiple occasions to cross-reference and compare the data; a valiant effort, though its efficacy would need to be adjudicated on a case-by-case basis.) A more theoretical example could be that of a quotation. If one were to quote from Book I of Plato’s The Republic, he could say, “Plato writes that ‘justice is nothing other than the advantage of the stronger.’” So saying, he would not be misquoting Plato. This, however, is a gross misrepresentation of Plato as anyone familiar with the philosopher’s writings will know. By engaging with even the whole page from which this quote was taken, any reader will see that this quote is stated by the character Thrasymachus, and that, continuing on with the whole of Book I, Thrasymachus is actually refuted by another character, Socrates, and shown to be incorrect—ostensibly indicating that Plato himself knows this to not be the proper definition of justice. The context from which the quote is taken is necessary to understand any specific claim—a reality of which Plato himself is a lucid expositor.

The Idealist method, therefore, is an intellectual engagement to abstract and theorize ideas—the goal is to focus in on some aspect of experience in itself. The idealist thinker attempts to overcome the issues of generating these abstractions by then continually reintegrating them with the whole from which they were abstracted. This creates what could be called an intellectual, dialectical process through which the whole and all its parts are gradually revealed in their entirety; the point is that the whole and parts mutually reveal one another through this continual exertion to have both revealed in their entirety. (Anyone familiar with Plato may also note that this seems, in some respects, very similar to the Socratic method—which clarifies why Plato is sometimes anachronistically referred to as an Idealist.) Of course, the precise understanding of how these abstractions and the whole are interconnected will vary from thinker to thinker, but nevertheless the basics remain true among those who are considered ‘Idealists.’ This also explains why they have come to be known as ‘Idealists.’ In each case, they are interested in inspecting things in the world in a way that contemplates the ‘ideal’ type of a given object, be that a book, politics, history, or a human person. To be clear here, ‘ideal’ does not mean ‘perfect’ (and all the baggage that term implies) but rather something like in accordance with its own character. This harkens back to the etymological origin of the term ‘ideal,’ stemming from the Greek term ‘ἰδέᾱ’ (idéā) meaning “form, shape, type, or sort.” The Idealist sees that the world has a plurality of things appearing within it and then investigates those things that appear in his experience to make them more concrete and known—something that makes it very similar to the philosophical school of Phenomenology (and we might note here that the English derivation of one of Hegel’s seminal texts is The Phenomenology of Spirit).

As a last note about Idealism, it should be emphasized that this is a philosophical method, not something akin to a ‘presupposition’ or ‘assumption.’ In some sense, I am of the view that philosophy should fundamentally be understood only as a method, a frame of mind—one in which the Absolute, Experience, Consciousness, Being, or whatever other term you fancy is capable of being rationally investigated. The only ‘presupposition’ possible to philosophy is that experience is rational and able to be known in a profound sense—though I think that this is hardly a presupposition, nor do I see how one could get beyond it (What would it mean for reality to be proclaimed incomprehensible? Does that not invalidate that very claim?). The ‘objective’ of philosophy, therefore, is mere understanding for its own sake; it is not for ‘control,’ not to describe ‘matter,’ not to recount ‘past events,’ but to understand the very structure of reality as it is. There may be other forms of knowing in one way or another (the status of these other modes of enquiry being subject to different conclusions depending on the Idealist thinker in question), but no other mode performs this same function of philosophy as they all assume something about the world to undergird their enquiries.

This is the school of philosophical thought which I have found most convincing and desirable to follow after. Anyone familiar with me will know that I am mostly studied in the thought of Michael Oakeshott, a late offshoot of the British Idealist Movement, though I also have a great affinity for R. G. Collingwood and F. H. Bradley who are representatives of what is formally understood as British Idealism. I wish to unpack as much of this school as I can as I believe they have much to offer the world of epistemology, specifically regarding how we separate different domains of activity within our experience. Most notably, these thinkers dominate the formation of my thought about the nature of history and praxis. My reflections to come shall be of this tradition of thought, both in critiquing various arguments they have made and considering why I tend to favour their methodology (or, perhaps, methodologies).