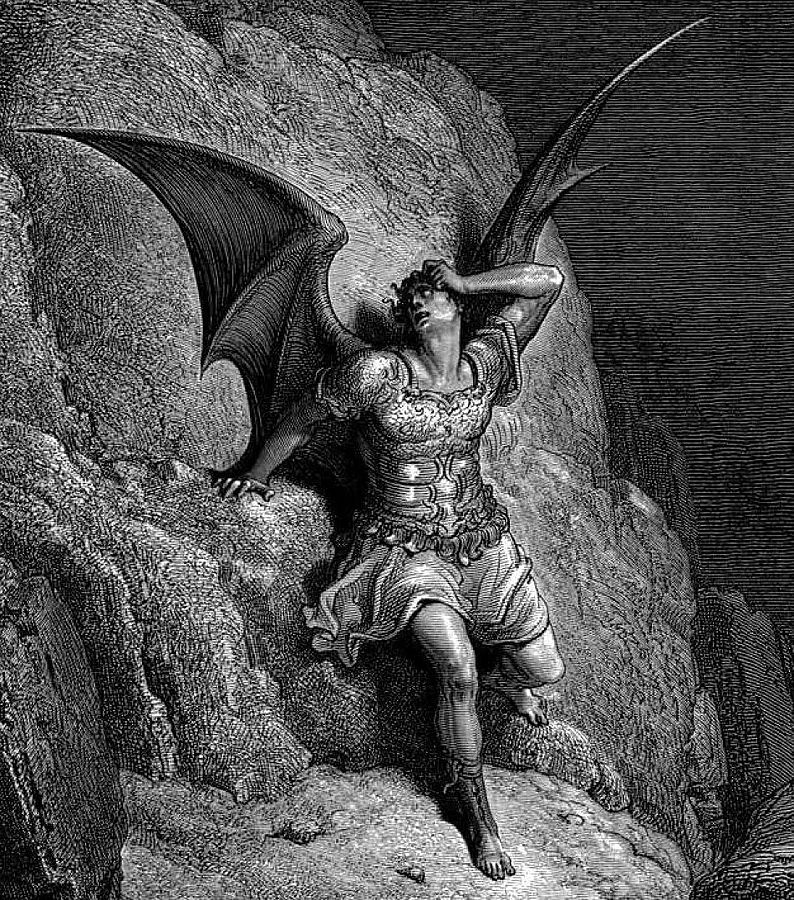

“A mind not to be changed by place or time.

The mind is its own place, and in itself

Can make a Heav’n of Hell, a Hell of Heav’n.”

I believe that it is fair to call our age one that is deeply ‘rationalistic.’ I realize that such a word may offer so many definitions as to be incomprehensible, having a meaning as warped as that of the term ‘ideology.’ What I mean, however, is nothing other than an eristic notion that every action must have a ‘reason,’ though what ‘reason’ has come to mean is little more than ‘the claims I put forth to justify my action.’ This view holds that if I think something is justified, it is justified; there is no further criterion. But know that in practical reality, such a form of ‘reason’ is destructive; it masks why we act and obscures the conditions in which we find ourselves: a sea of contingency that is practical life. We may think we have understood the calm seas, yet only God knows of what will happen when the hurricane comes upon us.

For my purposes here, I will refer to this warped notion of reason as ‘rationalization,’ for that is its true name. I make this distinction as I believe reason is real and can lead us well; yet we should never overestimate the reality that our capacity to reason rarely matches the true complexity of our circumstances—failure imminent in all we pursue. Worse yet: the principles of reason may be used erroneously and lead us afield from a proper view of ourselves, let alone one of the world in which we live. We must realise that we are in a world which we have not determined; to think something of the world does not make it so, our reason is a capacity—not to determine, but rather—to understand.

“Those who in fields Elysian would dwell

Do but extend the boundaries of Hell.”

One aspect of our experience which I believe is being regretfully eroded by this tendency toward rationalism is familiarity. The rationalistic mind has no room for the familiar, for it believes the familiar is not justified if it is without a ‘reason’ that the mind can immediately grasp. The notion of ‘tradition,’ of a ‘way of life,’ which is not self-consciously reasoned through at every step becomes repugnant to the rationalist. The rationalist questions all except his own capacity for ‘reason,’ demanding why we would need to dress in a certain manner or why a certain cuisine is favoured over others. In looking for supposed ‘timeless’ truths, he forgets that a man may be content simply since he knows where he is.

The word ‘prejudice’ used as it is today is, in my view, the emblem of this form of thought. To be ‘prejudiced’ in our society is to be beyond reproach—to think that someone has not thought through every aspect of his life? How deplorable! Yet, if we ask, does not much of our behaviour rest upon many prejudices? Have we meticulously thought through why we support our family members? Do we have a checklist ready for consideration of whom we do and do not consider a friend? What do we believe would be the outcome of trying to pursue such a line of reasoning? I posit that, if pushed with enough force, we will come to say that it is because it is all we know, not in the sense of knowledge but of what our experience has been.

“How far your eyes may pierce I cannot tell:

Striving to better, oft we mar what’s well.”

Our world of practice is one in which we find ourselves caught between what we have now and what could be at some time not yet come. The world we find is, perhaps more than we typically recognise, incomprehensibly complex. It is no mystery why the infant cries! He has not yet had the time to find a place in the world to call his own. This is, as far as I can tell, the aim of our lives: to live in a manner in which the present and the future bear little tension; to have a sense of identity in the world that, though not eternal, is enough that we may see the world as a gift and not a burden. And I believe that such a way of life is far simpler than we often estimate; indeed, I would guess that the ancients Plato & Aristotle were far closer to it than I.

My final note would be to point out the simple fact that, even in the case of the rationalist, the aim to change the present must ultimately rest upon the desire to have something familiar in the future. The hope is that the dreams we seek in the future will become the reality of an eventually familiar present; yet, what do we have presently that will be lost on such a path to get there? In finding what we esteem now, preserving those familiar things, and acting out of the sort of love necessary to maintain such a life, we may indeed make for a greater future, but without ever failing to strive for joy in the present.

“Not, Verweile doch, du bist so schön, but,

Stay with me because I am attached to you.”