A supposed ‘problem’ that has presented itself within the last few years is that of ‘cancel culture.’ I am inclined to think that this issue is rather overstated. A recent example is that of J.K. Rowling being ‘canceled’ for her comments regarding trans-rights issues. Some social commentators believed this represented the issue of ‘online mob rule’ while others wanted to bombard Rowling to send a message that her views should be condemned. What was notable about this was that nearly everything occurred online; my various social media feeds were filled with opinions about Rowling’s comments, yet I spoke with nearly no one who would speak about the issue in person. This occurrence does, however, interest me from the perspective of revealing certain ways in which we understand ourselves and those around us through the lens of social media and our online personas.

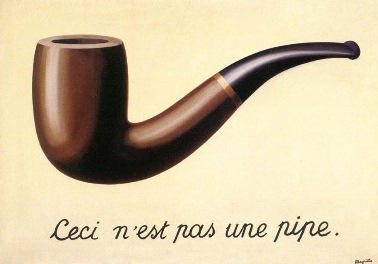

To make a rather benign observation which is certainly not original, it seems that our age of social media has caused something of a bifurcation of our selves. Our online profiles present an opportunity to create what we may call a ‘curated self’; an image of our own lives which can be carefully edited and cleaned up in a manner which the fullness of practical experience tends to make impossible. We need only look at someone we live with in juxtaposition to their online profiles; these two images can present themselves as entirely different entities with only a glimmer of connection between the two.

Now, in itself, there is nothing inherently wrong with this. Much in the same way that no one writes down their prior blunders and failures on a CV, it is understandable that we do not add embarrassing personal details or tragic life events to our social media profiles—at least not in a manner which well approximates their practical correlates. There is thus a distinction between who we are truly, even if that is not understood in its entirety, and the idea of ourselves which we display through our online profiles. Our Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter presences become an abstraction of the totality of ourselves; to look to these abstractions to attempt to understand the people they represent must leave something wanting.

If we understand that this bifurcation has occurred, it seems to me that there is little to worry about. What concerns me, however, is the possibility that such changes to the nature of our experience may go unnoticed; for a generation of people like myself who do not have extensive memory outside of a world saturated by our online presences, it can be difficult to even understand what it means to live without that curated persona of ourselves. This leads me to the question: what does this creation of the curated-self offer and what should we be wary of?

One thinker I immediately went to in consideration of this question is the philosopher Martin Heidegger; in his later work, he focused intensely on the nature of experience in the modern, technological world. In his essay, “The Question Concerning Technology,” he reviews what the essence of technology in the modern world is and what problems it may present to our self-understanding. To perform this task, he pulls apart what is implicitly held in the term ‘technology.’ Heidegger focuses upon one of the two root words of which ‘technology’ is composed: ‘techne’ (the other being ‘logos’). If we attempt to translate ‘techne’ directly into English, we may use terms such as ‘trade,’ ‘craft,’ or ‘art.’ A simple definition would be the composition of a series of skills which allows for the revealing of something new; in this way, the carpenter reveals the chair from the raw lumber, the blacksmith a horseshoe from raw iron, the stonemason a wall from a pile of stones.

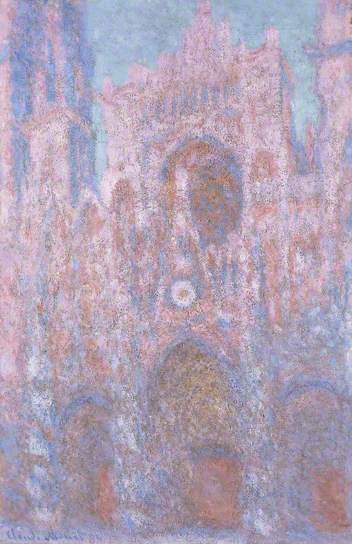

This is not in itself a bad thing. For Heidegger, this is neither a commendation nor a condemnation of techne, but simply an attempt to understand what it is. What Heidegger further reflects upon is that this revealing power of techne is only possible when it “enframes” our view. What he means is that revealing cannot happen if we are entirely open to possibilities; for any tradesman to work, he must buy into certain principles and assumptions to do his work. Again, this is not a negative. It has, rather, both good and bad effects—it allows for something to be revealed (like the chair from the raw lumber) which would have been impossible without the enframing, but this also causes a narrowing of what is deemed as possible (a carpenter may see a pile of stones and see nothing of value despite what is possible for the stonemason).

What concerned Heidegger more is what this concept of ‘technology’ in its totality means. It seems to be something of a departure from mere ‘techne.’ The root word ‘logos’ has several meanings, but it typically is associated with words, speech, and reason. Thus, to be ‘technological’ is to pursue the reason of techne. The risk here is that for us to associate these two conceptions leaves us perpetually ‘enframed.’ Heidegger is pointing out that as technology becomes more pervasive in our lives (which it surely has since 1954 when Heidegger wrote this essay) we begin to lock ourselves into certain ways of understanding ourselves and the world around us. If this seems dramatic, consider how deeply reliant the average North American is upon electricity—who among us could even imagine life without electricity, let alone the many other technological innovations which pervade our lives?

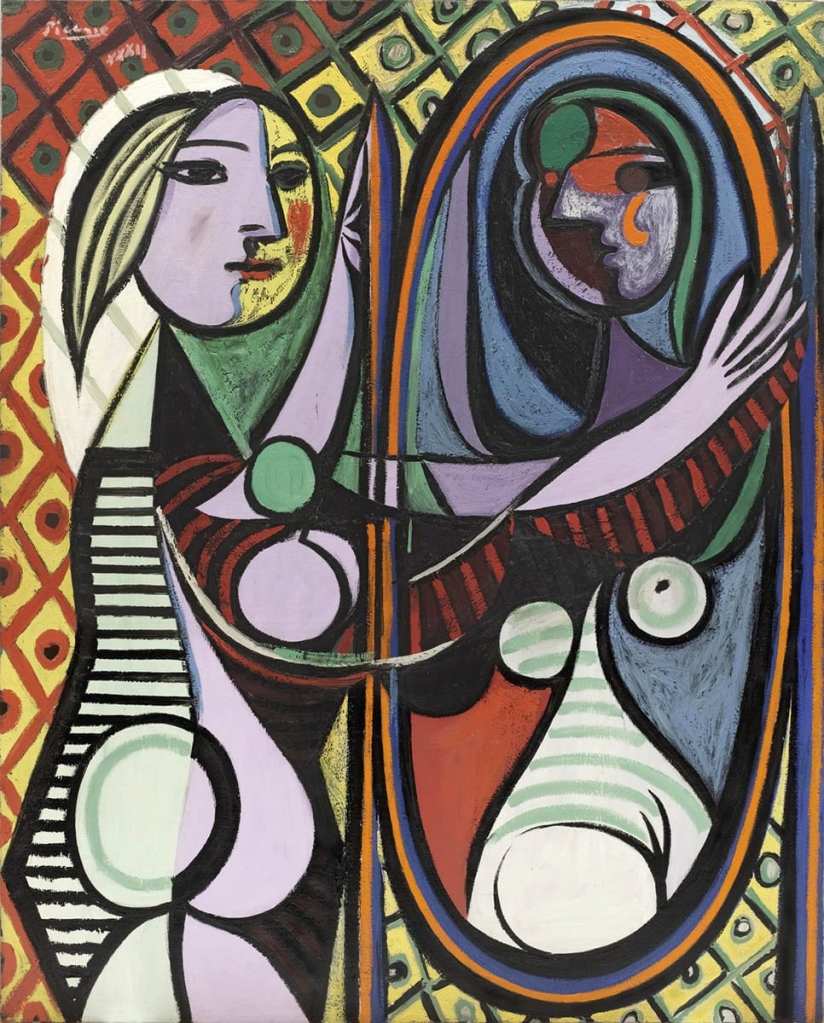

With this reflection upon technology from Heidegger in mind, let us return to the prior discussion of social media and what it means to present ourselves online. Though it may seem odd, we may describe the procurement of our online profiles as a sort of ‘techne.’ No doubt our social media profiles exist in a technological space, but as well the designing and maintenance of these profiles itself could be considered a sort of ‘craft’ or ‘trade,’ with some of us being more effective than others. What may strike us as confusing, however, is what the medium of someone creating an online profile is. If the carpenter’s trade reveals something from within the raw lumber, what material is the social media user working with?

The obvious answer to this must be our personal experiences themselves. Granted, this will take a variety of forms. Our social media profiles may be filled with pictures of ourselves, places we have been, social movements we support, or art we enjoy among many other things, but all of these things nevertheless present some aspect of ourselves in a consolidated form which is based upon, but lesser than, the totality of our experience. This puts us in a much more peculiar position than that of the carpenter, blacksmith, or stonemason, for the ‘techne’ of social media is reshaping how we present ourselves, rather than some organic resource of nature such as wood, ore, or stone.

Now, we can ask why we have moved in a direction of this being so rampant in our lives; how did this come to be? I believe this to be inherent in the structure of social media platforms themselves; not in that they were built to provide such a ‘techne,’ but rather that this is an inevitable outcome of the way they were designed. Platforms such as Facebook or Instagram are structured so as to allow us to conveniently share parts of our experiences with those who may want to see what we are doing in our lives, which I believe is a wonderful intention. If this becomes the main mode of contact between people, however, they will begin to believe that they understand others based upon profiles as opposed to through intimate, personal relationships. At that point, it would seem natural for us to desire to design our profiles in such a manner that would allow us to be perceived as positively as possible.

In some sense, these carefully curated-selves of the online world may allow us to see the sort of people we want to be and what sort of issues we would ideally like to see solved. This revealing, however, must come at a cost. In the same way that a carpenter carving a decorative pattern into the back of a chair necessitates the loss of some wood shavings, creating our idealized selves on our social media platforms will cause the loss of some details which are critical to us as whole persons. When the ‘enframing’ of social media is used to present us online, we may lose critical details that are necessary to have a full relationship with that other person. To only interact with someone over Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter makes it very difficult to share a laugh with that person, enjoy a hug or kiss, know what pet peeves they have, or know their daily habits. Conversely, because this ‘enframing’ is being applied to our own experiences, we run the constant risk of believing our online presences to be ‘more true’ than the whole of our experience since it is the version of ourselves that more people interact with and know. This may cheapen many aspects critical to our enjoyment of life; how could we ever use our social media to fully replicate the joy found in gazing up through a budding tree, radiant with the glow of the sun, as you listen to family of birds singing a joyous song of Spring?

I imagine that I have likely said in a slightly different manner (while using too many words) something which many of us intuitively understand about our own experiences in using social media. I know many people, myself included, who have sudden impulses to get offline for several days at a time or even delete their accounts altogether; I also know of many people who have expressed confusion at their own constant scrolling through social media apps despite getting nothing out of it. Perhaps, in looking at these things reflectively, we may begin to understand what is happening as we interact with the contemporary forms of techne, and in doing so we may decide that some sort of change in perspective is in order.

Wenn wir uns selbst fehlen, fehlt uns doch alles.

-Goethe

I enjoy reading your blogs keep going

http://www.sudarshanpaliwal.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

A slightly lighter read than your other blog posts, yet just as entertaining and thought provoking. I appreciate the variety.

LikeLiked by 1 person