“Call it, he said.

She looked at him, at his outheld wrist. What? She said.

Call it.

I wont do it.

Yes you will. Call it.

God would not want me to do that.

Of course he would. You should try to save yourself. Call it. This is your last chance.

Heads, she said.

He lifted his hand away. The coin was tails.

I’m sorry.

She didn’t answer.

Maybe it’s for the best.

She looked away. You make it like it was the coin. But you’re the one.

It could have gone either way.

The coin didnt have no say. It was just you.

Perhaps. But look at it my way. I got here the same way the coin did.

…

Then he shot her.”

-Cormac McCarthy, No Country for Old Men

After finally watching the much-recommended film No Country for Old Men, my interest was piqued in the author behind the twisted, neo-noir western: Cormac McCarthy. My local bookstore had a copy of the book by the same name as the film as well as another much-lauded novel, The Road. I began with the latter, an apocalyptic tale depicting a father whose entire life is based on the happiness he may provide for his son—a wonderful book I would highly recommend. What grasped me much more readily, however, was the character of Anton Chigurh from No Country for Old Men.

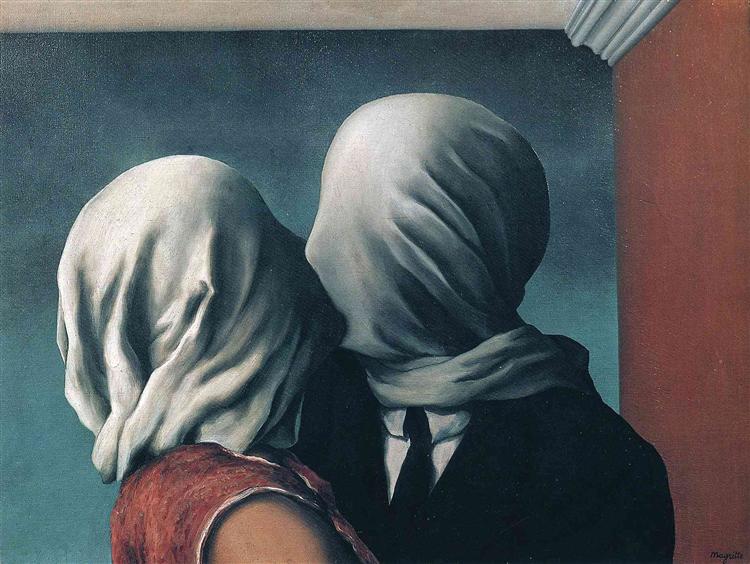

Brilliantly portrayed by Javier Bardem in the live-action rendition, the Chigurh of the written word adds yet another layer of unease to a character that defies definition. No Country for Old Men is a difficult book to describe, as it is near impossible to call any one character the ‘protagonist’ or the ‘antagonist.’ Chigurh is, no doubt, something of a malevolent force; but to describe him as ‘evil’ would seem to betray his character. Rather, he is more like an agent of fate—he fundamentally believes that there is no rhyme or reason to one happenstance as opposed to any other, a murder being of no more or less consequence than the toss of a coin.

McCarthy’s depiction of this character is chilling. Worse yet, there is something understandable about this character, especially in the nearly amoral (or immoral, perhaps) world that McCarthy conjures up throughout the book. The entire plot is driven by a man (neither good nor evil, neither hero nor villain—just a man) stumbling upon a case of money. It is chance that provides this man with millions of dollars for no labour; perhaps it is only chance that he should be pursued by ruthless outlaws and one of the most lethal characters to ever grace the pages of a literary work. No Country for Old Men confronts us with a debate hardly new to our age: is everything in our world determined? Are we free? What are the implications of being determined or being free? Though these thoughts began with McCarthy’s disturbing vision of Chigurh in his twisted, western world, it did give me pause to think, to re-evalute, and return to a text much deserving of perpetual consideration: St. Augustine of Hippo’s City of God.

To understand a critical passage of Augustine’s, we must first backtrack through some prior thinkers to understand to what exactly Augustine was responding. Since antiquity, the problem of causation has plagued several thinkers. One highly influential figure among the ancient Greek philosophers was Epicurus who argued in favour of what may be termed ‘atomistic determinism.’ Epicurus believed that there were things called ‘atoms’ which were essentially the smallest possible things, defined as such due to their supposed indivisibility (this is where our modern, scientific notion of atoms comes from, however the definition has surely changed). Thus, Epicurus’s notion of atomistic determinism argues that, since time immemorial or perhaps eternally, there has been the motion of these atoms crashing into one another, causing shifts this way and that. Like in a set of dominoes, everything has been determined from the outset to be as it now is, and everything shall move in the future based upon what has gone before it.

Evidently, this caused problems for understanding what it means to make choices. If I choose a chocolate instead of vanilla ice cream cone, was I always destined to make that choice? What does it mean to even choose within such a deterministic framework? Epicurus attempted to get around this problem by arguing that sometimes these determined atomic movements could have spontaneous little ‘swerves,’ causing an anomaly that would not occur in the way one would have thought the determined events should go. Evidently, this caused more problems for Epicurus than it solved. Would not that swerve need to be pre-determined within the prior conditions? If so, it should be irrelevant as it would merely be another part of the chain; if not, where does that swerve come from? Would that not be from beyond the atomistically determined system? As one may expect, this argument begins to lose its steam when trying to understand ourselves and our capacity to reflect.

One critic who took up charge against Epicurus’s claims was the great Roman statesman, Cicero. He wrote a text called De fato (On Fate) on this subject, though much of the original text has been lost to the abyss of time past. We presently have only selections, largely from the middle of the text, which do provide some insight into Cicero’s objections. In brevity, Cicero rejected Epicurus’s framework as it completely undermined the bulk of human experience: reflection and judgement. Being a man of politics and law, Cicero was led to believe that human will matters, and we must thus be allowed to make decisions. If our decisions are entirely determined, what does it mean to ‘act lawfully’ or ‘be moral?’ Indeed, it would seem the entire endeavour is meaningless since causation would have had it this way regardless of human will, and there is no honour to be granted in being lawful or moral.

Cicero’s objections, though, led him to a rather peculiar conclusion: existence must be a kind of indeterminacy which we determine through our will. As opposed to the rigid confines of Epicurus’s view that restricts us to having no will at all, Cicero opted to bend the branch back in entirely the opposite direction. Cicero went so far as to object to even the gods having power or knowledge of the future; the future was merely a completely unmolded clay that could never be known until it became the present. This implies that we actually determine our being through the act of willing. I should stress that there is a difference between determining our being and designing our being. I do not want to make it seem as if Cicero was arguing that we are omnipotent creatures who can remake reality at will; rather, it is that meaning is sought fundamentally by the man that makes moral and lawful choices within the flux of an pre-existent but nonetheless undetermined cosmos. In this way, Cicero’s argument has a flavour akin to the 20th century French Existentialists such as Camus and Sartre (despite there being many differences between these Frenchman and the Roman statesman).

We have thus moved from the rigidity of Epicurus to the flux of Cicero; perhaps there are many of us considering this issue who may be just fine with one of these two theories. I believe, however, that there is a middle ground established by the great St. Augustine of Hippo—a middle ground far more stable and reflective of our experience than the prior two options. In his great work of political thought, City of God, Augustine addressed Cicero head-on. Before unpacking his objection to Cicero, however, it may be wise to begin with a pre-emptive note on a major difference between Augustine and Cicero.

Augustine is a fundamentally Christian thinker. If one does not understand the precepts of the Christian Faith, it becomes rather difficult to completely unravel Augustine’s writings. This is surely important to this specific subject matter, particularly in some of the ways which he refutes Cicero. When Cicero referred to “the gods,” he was referring to those of the Roman system—incredibly powerful, immortal beings, that were nonetheless limited in the scope of their power. Augustine latches on to this invocation of the gods and complains throughout that Cicero does not understand “God”—but this should be expected. Cicero was a pagan, not a believer in Christ, nor a Jew, nor a man who would have any education in the Abrahamic traditions. To object that Cicero misunderstands “God” is akin to being mad at Plato for not having written in English—it lacks a contextual sympathy and understanding. Despite this glaring fault in Augustine’s rejection of Cicero, we can still gain much from understanding how Augustine conceptualizes God as a Christian and how this affects his notions of determinacy and free will.

To understand Augustine, we must have—at least—a preliminary understanding of the Christian God. The God of the Bible is the ground and source of all Being; He is not one being among many that is in control of everything, but rather He is the necessary condition for existence. A cosmos composed of things that come to be and pass away must have a stable ground upon which everything rests—this is God. God pervades all of existence, and all of existence is conditioned by Him. There is nothing beyond God, and nothing can be which is beyond Him. This is where the three common notions of God come from: omnipresent, omnipotent, and omniscient. This leads to two things that can be determined about God: He is eternal, meaning that He is actually beyond time unlike merely immortal gods who experience all time chronologically from within time; and He is perfect insofar as he lacks nothing and subsists perpetually in Himself (unlike man, by contrast, who requires many external goods to survive). This extremely brief understanding of God will suffice for now, and I wish to stop here before I cause a Christian theologian to spontaneously combust.

With this definition in mind, we may quickly understand why Augustine objected to Cicero’s statement that not even the gods could know the future. In Cicero’s view, this point was being made to emphasize that the human will is a necessary and fundamental faculty we possess; what he missed, and Augustine is sure to note, is that this view erodes the capacity of evaluating one’s moral choices at all. If the future is only choices made in a cosmic flux or vacuum, then there is no fundamental existing reality by which to evaluate if we are choosing what is good or what is moral. Augustine’s response is that God can indeed have foreknowledge of what we do and what we will choose, or rather He must, for He is the ground of all Being and knows every possible outcome before we even consider it. Without Him and his creation, there is nothing for us to choose or understand—we are not the creators of that which we engage with and interact but rather the interpreters. Does this, however, preclude our capacity to choose? What distinguishes this view from that of Epicurus’s atomistic determinism?

What separates Augustine from the Greek philosopher is that his understanding of God does not confine man to a merely material determinism in the way colliding atoms necessarily does for Epicurus. Rather, matter, like all else in the extant universe, comes to be and passes away. Thus, for Augustine, it cannot be the determinate ground of all existence. Instead, Augustine believes that there are both material and immaterial realities which all emanate from God; freedom is such a reality that exists alongside, but is not negated by, material causality. “Our wills themselves are in the order of causes, which is, for God, fixed, and is contained in his foreknowledge, since human acts of will are the causes of human activities. Therefore he who had prescience of the causes of all events certainly could not be ignorant of our decisions, which he foreknows as the causes of our actions.” As opposed to attempting to generate a system of thought that localizes on a single aspect of experience, such as matter or the human will, Augustine concedes both and posits the necessity of God who undergirds the entire reality, allowing for the possibility of our free will to choose what is good—a condition not defined by us but rather discovered through our exploration of His cosmos as He already knows.

One possible objection to Augustine could be: “What if this is mere psychological projection? You simply believe that you have freedom and then you project that onto the universe despite it not being true.” To this, there fundamentally is no good answer. I suppose all we can do is ask, “How do you act?” It seems to me that to suppose any one concept to be ‘psychological projection’ runs the risk of raising the question: “is psychological projection psychological projection?” It simply will not get us anywhere. To ironically quote the infamous atheist speaker, Christopher Hitchens, when he had been asked if he believes in free will he stated, “Of course I do; I have no choice.” The nature of our very experience is that of judgement; there is no act that does not entail some form of deliberation. Even if it is the reaction to pull one’s hand away from the hot stove, there is an albeit brief thought of pain that causes the reaction to end that pain. To question freedom along with Epicurus is to reject ourselves; to question reality along with Cicero is to blind ourselves.

This, I will readily admit, has been a long excursion from the world of No Country for Old Men and the bone-chilling Anton Chigurh. So, what has the point been? Do I believe that if I were a character alongside him that I could have convinced him to let go of his deterministic (perhaps nearly Epicurean?) view that leads to so much violence and mayhem? Probably not. Instead, I merely hope that this may provide some fertile ground for thinking about the condition of our choices, what it means to be free, and the nature of the cosmos we find ourselves in.

*****

“This is your command, and it is carried out in full, that every mind not conforming to your law is its own punishment.”

-Augustine, Confessions, I.vii.19

You remind me very much of the character Chidi from The Good Place.

LikeLike

I’ve never been able to stomach that show so perhaps I’ll just take that as a compliment?

LikeLike

Not in every way of course, but the good ways. So yes, please take that as a compliment. It is funny you don’t like the show seeing that it is about ethics and moral philosophy. What do you not like about it?

LikeLike