For some time now, though there seems to have been a recent uptick, I have seen many social media posts that express a sentiment of pushing all people to be profoundly unique, innovative, and beyond the status quo. Just recently, I saw an image circulate that said, “Take the risk. Choose the unknown path. Because when you are able to jump and trust yourself in the process, chances are, something very beautiful will come from it.” This is just one example of what I have seen circulating for the last four to five years. The expression of this desire for the extraordinary is not, however, merely the subject of some throw-away social media posts and does indeed come in much more complex forms of advocacy.

To provide a more substantial version of this, the polymathic Peter Thiel delivered the Wriston Lecture for Manhattan Institute (MI) in 2019 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E-IaSS0bbGU&t=1243s). If you cannot stomach the lecture, I will at least provide some of my takeaways along with a little background. MI is a thinktank which focuses on market solutions for social issues, advocates minimalist government policy, and is aimed at modern individualism and capital growth. They have an annual lecture called the ‘Wriston Lecture’ which has now gone on for 33 years, in which they invite a speaker who has demonstrated himself or herself to be a formative personality of the era and give their thoughts on how to keep ahead of the pack (though I am still unsure of who exactly comprises the pack). Last year’s lecture was delivered by the aforementioned Peter Thiel.

Thiel, no doubt a brilliant man in fields ranging from economics to physics to political theory, expresses concern about the fact that his homeland of America is no longer the same nation it once was in developing world-changing technology such as the automobile or the skyscraper. Thiel himself is one of the founders of PayPal and was the original external funder of Facebook, and thus is emblematic of what we may consider a ‘profoundly unique, innovative, and beyond the status quo’ person. It is essential to note that Thiel is not merely presenting a view of ‘pushing us all into the future’ in any direction; Thiel has something of a libertarian impulse and is therefore warry of technological advancement such as ‘big data.’ Instead, he desires for innovation in ways which allow for further advancement of individual autonomy, creative thinking, and idea sharing, which I believe reinforces my claim that he is pushing for all men and women to be “original” in some profound capacity.

Now, I have no desire to completely reject what Mr. Thiel or the many social media users are expressing when they advocate for others to be different and think outside the box. There is much to be said for the capacity to think creatively, and there is certainly amazement to be found in watching another person reach for the stars and nearly grasp them. My worry, however, is that there has been an overemphasis of this striving for innovation in our present time, and I wish to defend the alternative by demonstrating its necessity and its great potential for enjoyment: a Defense of the Trodden Path. As may be no surprise to many, I am once again inspired here by the work of my philosophic hero, Michael Oakeshott. I will begin by using one of Oakeshott’s essays to demonstrate the need for a stable, non-innovative ground upon which our common-life rests before discussing the joy to be found in common life.

In his essay “The Tower of Babel,” (published in Rationalism in politics and other essays in 1962, not his other essay of the same title from 1983) Oakeshott reviews the development of moral thinking in what is conventionally considered the ‘Western World.’ Despite that Oakeshott is typically considered a simple “conservative,” this essay provides a solemn critique of the West’s tendency to pursue abstract ideals without a practical understanding for the content that is necessary to make those ideals a reality. Oakeshott believes that this has been a nearly constant issue in Western thought, going back to ancient societies and perhaps even having Biblical origins, hence the title of the essay referencing one of the stories found in the Book of Genesis.

Oakeshott does not disregard the very real desire for people to tread their own paths or pursue new ideals; he acknowledges that “the pursuit of perfection as the crow flies is an activity both impious and unavoidable in human life.” There is no doubt that it will occur, but we also know that it will always come with a cost, though perhaps we are willing to pay depending on the outcome. Despite the possible profits of such risk, it is also inevitable that there will be a resistance from both the world itself and the present human structures we have made to whatever new innovations that we may dream up.

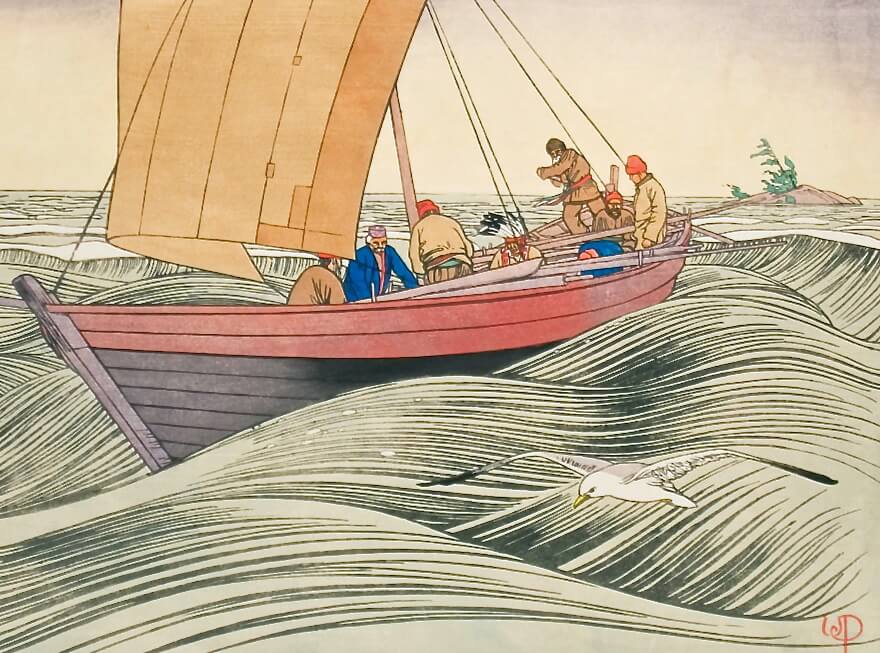

Pursuing what we might believe to be better “involves the penalties of impiety (the anger of the gods and social isolation), and its reward is not that of achievement but that of having made the attempt.” In Oakeshott’s view, new advancements in nearly any endeavour of life will be met with some level of hostility and resistance, but that does not make the attempt futile; rather, there is something honourable about making the attempt at all for it explores the full range of human possibility (as provided to us by God, the gods, or the forces that be—depending on your outlook). This pursuit will also often lead to failure, requiring a reorientation from familiar ground, as the novelty of the innovative situation will likely lead someone into uncharted waters and he or she will soon falter in the depths of the unknown sea.

It is because of this near inevitability of failure that Oakeshott argues that the pursuit of the better is “an activity, therefore, suitable for individuals, but not for societies.” Thus, we have come upon a distinction in who may perform an action: either one of the many among a group or the whole group. The point being made is that an individual who pursues perfection, a better tomorrow, will have the stable society from which he sprung to fall back upon. When his exploration of the unknown waters becomes too difficult, he knows he can swim back to the place from which he came and there will be arms outstretched from the ship of civilization to embrace him once more.

Oakeshott continues that “for a society [to pursue an ideal], on the other hand, the penalty is a chaos of conflicting ideals, the disruption of a common life, and the reward is the renown which attaches to monumental folly.” When everyone is striving to change our world, being the social whole that we communally inhabit, it can turn into a storming sea of the night into which we all have the risk of drowning in the dark. Common life, what may be called the ‘common good,’ is something that is tremendously difficult to simply dream up; it is comprised of many layers of mediated interactions, agreements, and customs which, though we may not fully understand them consciously, allow for us to have contingent, proximate markers that subdue the chaotic potential that is always under the surface of our societies. No single person generates the social circumstances that allow for us have this stable ground of culture which allows for us to navigate the stormy, unknown seas of experience; rather, there is great value in seeing how those who have come before us have maintained the ship up until now in order that we may keep a fairly even keel.

Steering the whole ship to an unknown locale may bring our society into worse waters and drown us all; or we could run the risk of moving our ship too quickly into what may indeed be a better place to sail, but the rapidity of our journey causes damage to our hull that we overlooked repairing and causes us to sink upon arrival. This is why we must have those brave men and women who first dive into the rough waters on their own to search for smoother sailing or even a remote island upon which we may rest and recoup for just a moment. Our whole ship, however, can follow them only by maintaining present knowledge of how to sail the currently known waters and slowly move us all to where things may be better—but this should be done with extreme caution and a love for the ship and ones fellow seamen (for who would trust their way of life to someone who has no care for it?).

This picture I have painted seems to allow for all honour and glory to be given to those particularly adventurous few who are willing to jump ship and swim on their own power in hope of finding a better tomorrow. I would not, however, share this idea that adventure necessarily makes for a better life. Though I understand the appeal of honour and glory, we may note that the men, women, and children who remain on the ship nevertheless have their own sorts of delights to be found upon the ship while ensuring that it remains afloat. A brief exploration of this seems to me to be in order, although I fear that its contents will be familiar and benign to most of us—my hope is merely that in reviewing them explicitly, we may take a moment to reconsider where we find the value of our lives.

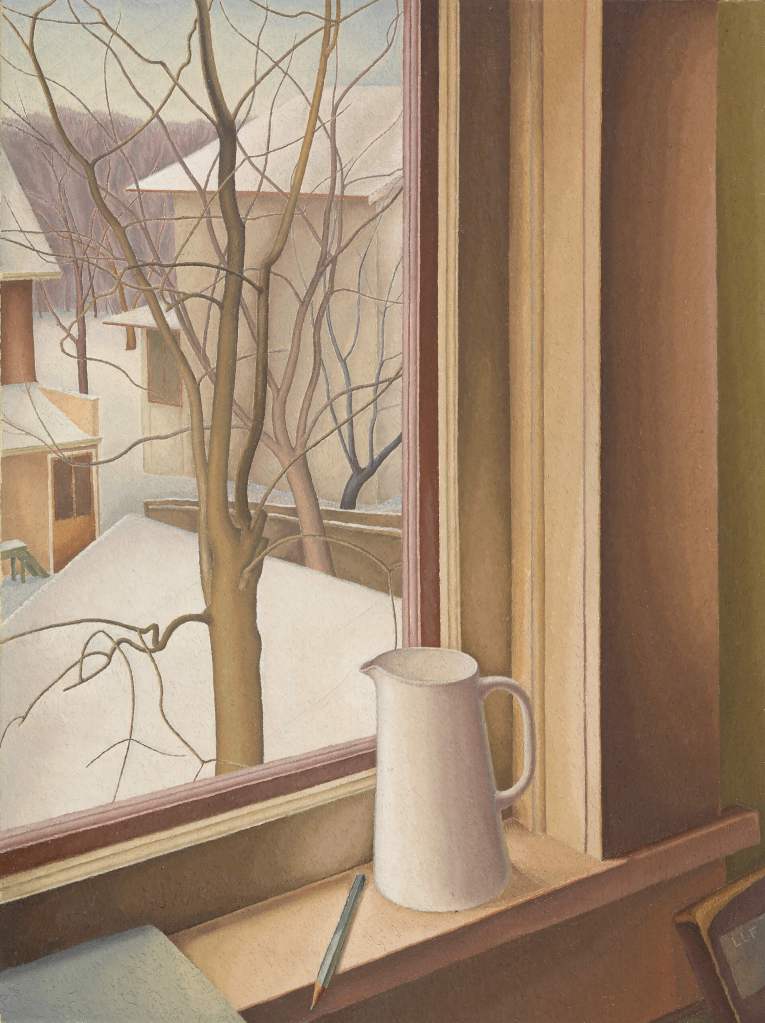

Those who remain firmly aboard the ship will be those who bear the chores of maintaining the vessel and the practices that allow it to keep sailing. Perhaps this ranges from organizing the labour of one’s fellow sailors, to repairing the ship itself, or preparing food for the crew to maintain their strength. This is not so different from our own experience upon the land if we wish to move away from my analogy for a moment. Ultimately, the purpose of our communities should be just that: communing to provide goods for the life of all. We aim to work ensemble because we will fair better than if we merely stand alone, though this does not negate the individual wants or desires we may also be able to partake in. What joys compare with that of seeing family, relaxing with one’s friends, singing or dancing together, or going to sleep somewhere which we can confidently know that we will awake in the same place the next morning safe and sound? These are delights which may be the very content of a deeply meaningful and satisfying life, and these are all aspects of experience that would be foreign to our lone adventurers. Unfortunately, we seem to frequently forget such wellsprings of happiness since they are all too familiar to us, and we only see their unquantifiable value once they have slipped from our grasp.

In a somewhat uncharacteristic fashion, I would like to share the story of a man who helped me to understand this. A couple of years ago, in the third year of my undergrad, I went for a beer with one of my professors every other week or so. He appears exactly as you would expect a (then) seventy-nine-year-old professor of literature to look: always in a sweater vest, speaking slowly but always clearly, and almost never without a smile from ear to ear. He certainly did not need to be teaching and was only conducting his European literature course out of a love for what he does (and he is in fact still teaching today). He is equally interested in the lives of his students as he is in his work, and always offers to go for beers any time his students are available.

One time, while sitting at the bar sharing a pitcher of Moosehead, I asked him if he found that his career as an English professor was the main source of happiness in his life. Over his career, he had received several teaching awards and acted as chair of the English department for many years; I assumed the answer to my question would be a simple yes. He took another sip of his beer, placed his pint glass on his coaster, and calmly shook his head and said, “No; though I see why you might think that. My career has been wonderful, and I have enjoyed teaching, but my students and colleagues do not know me that well. They are not the ultimate judges of my character. I would think that most of them simply could not be, given that most will only know about me or know me in passing. What has always mattered to me is that when I go home and see my kids, they run up to me with love because they are genuinely happy that I am their Dad.”

Now, I feel there are two main points that I should make for this picture I have painted to become a touch more concrete and pertinent to our lives. The first is that we need not view those who are adventurers and those who walk the trodden path as separate individuals—indeed, there may be room for us to balance both over a lifetime. The second is that we do indeed need both, for to only swim out into the open sea leads to the sinking of the ship, while only maintaining the ship leads to a lacking sense of adventure in searching through all that the wonders that experience has to offer us.

On the first note: there is nothing to say that a man or woman cannot have both a wonderful life within what may be considered the ‘trodden path,’ focusing on family and community, while also having a component of his or her life that pushes the boundaries of some limited area. This may indeed be best seen in a life of art. Though a man may be a father focused mainly upon his family, he may also be a wonderful guitar player who plays at the local bar for everyone in town on Saturday evenings. What is essential here is that a delicate mean is struck; each of us ought to understand the foundations of what make life manageable and stable, while having these adventurous activities on the side that allow for an escape, something to take part in for its own sake and which can be explored whenever the demands of trodden path have been met.

On the second note: I do believe that it is indeed important for us to have these little escapes from the work of communal ties and maintaining the foundations of life. If we are simply providing the necessities of life, there may be a risk of life becoming monotonous. Having an activity which we may escape to, be that painting, poetry, tinkering with one’s car, playing tennis with a friend, or simply going for a walk with no destination, provides a way to break up the constant demands of life. It could even be a way to connect with someone whom we would not ordinarily encounter or with whom we would associate. If we allow these activities to become the whole focus of our lives, however, we risk falling away from providing the basic structures we need to live.

My aim here is not to have entirely subverted the narrative put forth by Mr. Thiel or anyone else who supports the pursuit of individual innovation or originality. As I hope I emphasized enough, we can leave room to pursue such endeavours in addition to having a respect for what we hold in common. What cannot, in my view, be advocated for is a sense of individual pursuit that destroys our capacity to hold anything in common; I am unsure that there is a way to pursue a life of individual originality if there is no community. I must admit, though, that my hopes and aspirations for this sort of community may be little more than a fantasy in our present times. If that is the case, I hope to have merely provided a light reprieve from the demands of the current days.